In music history the curse of completing a ninth symphony as a harbinger of a death plagued composers after Beethoven, including Schubert, Bruckner, Dvorak, and Mahler. Working on the earliest Danish artist of international fame, Melchior Lorck (1526/27-ca. 1583) seems to have held similar portents, akin to Ludwig Burchard’s lifelong devotion, never completed, to compile a comprehensive catalogue of Rubens’s paintings (now nearing posthumous completion by a team of art historians through Antwerp’s Rubenianum). In the case of Lorck, Erik Fischer (1920-2011), keeper of the Print Room at Copenhagen’s Statens Museum, devoted his entire career to compiling a Lorck catalogue, also never realized during his lifetime. His project has now been carried to completion by Ernst Jonas Bencard and Mikael Bøgh Rasmussen, but they in turn fell prey to another aspect of the “Lorck curse,” largely problems with chosen publishers that delayed this final volume of the catalogue for fifteen more years. Meanwhile, this author reviewed the previous four volumes as well as the 2023-24 Copenhagen Lorck exhibition (Sehepunkete, 2010, http://www.sehepunkte.de/2010/12/18204.html) and this journal (April 2024; https://hnanews.org/hnar/reviews/melchior-lorck-facts-fiction-interpretation; as well as by Mara R. Wade: https://hnanews.org/hnar/reviews/melchior-lorck-an-artist-in-transit).

Lorck is famous for two grand projects, based on a personal visit to Constantinople with an embassy from the Holy Roman Empire to the Ottoman Empire in 1555-59. Both works, intended for publication, remained uncompleted at his death: a twelve-meter-long panorama drawing of the city skyline (Leiden University Library; Volume 4), probably intended to rival woodcut city view friezes of the sixteenth century, but never executed by carvers; and a woodcut series, partially completed, for a would-be Turkish Publication (Volumes 2-3, but also catalogued here). That work was only published posthumously as a torso without original commentary during the following century, beginning in 1626.

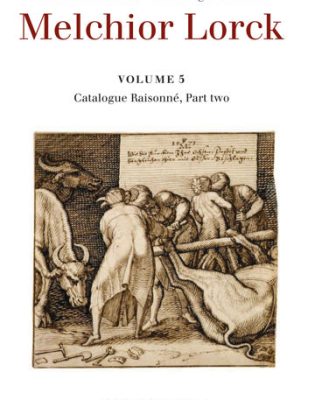

To a certain extent, this rigorous catalogue, comprising 274 works, most of them signed, many dated, needs to be supplemented with a narrative from Volume 1, Lorck’s life and works. Each image is numbered chronologically, regardless of medium, though most are graphic works. Inscriptions are transcribed and accompanied by English translations for each entry, and prints are itemized by collections.

Early etchings, The Pope as a Wildman in Hell (1545,1; after Lucas Cranach the Younger, a new discovery) and derivative portraits of both Martin Luther writing (1548, 1) and Albrecht Dürer in profile (1550,6), suggest interest in reaching a Lutheran audience. While these works might indeed convey young Lorck’s own religious views, such works might also have been smart commercial marketing in Denmark. The artist also experimented briefly with grand history scenes, a large drawing: Liberation of the Jewish People from Babylon (1552,2; San Francisco, Achenbach Foundation) and a painting: Story of Esther 1552-54,1; Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum), the latter from the Ambras collection of Archduke Ferdinand II of Tyrol. Several other graphics offer emblematic animals, notably a Tortoise above a Coastal City on tinted paper (1555,3; London, The British Museum).

From the embassy period, several intaglio portraits emerged, including a profile of ambassador Ogier Ghiselin de Busbecq (1557,1) and two other imperial ambassadors (1556,2; 1557,2). The first local Turkish drawings, usually combining chalk and ink, date from this period (1555-59), plus a striking rooftop cityscape, viewed from his residence window (1555-59,1; Copenhagen). Ink studies of local antique monuments, such as imperial columns and obelisk pedestals, form a cluster, dating from a half-decade, 1559-64. The first connection between a drawing (1561,4; Paris, Louvre) and a later woodcut (1576; no. 49) links Dromedary with Timpanist with the eventual Turkish Publication.

Many new insights accompany Lorck’s most celebrated independent engravings. Adapting the format of Dürer’s engraved portraits with inscriptions on a ledge, such as Federick the Wise (1524), the artist produced a bust likeness of an aged Sultan Süleyman (1562,1) and a complementary image of Persian ambassador Ismail (1562,2), the former with Arabic and Latin, the latter with Persian and Latin, translated. As part of the attainment of imperial noble status, Lorck’s name here is altered in the Latin to “Lorichs.” The date attributed here, rather than 1559, as cited in the Latin, stems from the print’s possible association with that year’s coronation of future Emperor Maximilian II, a ceremony attended by an Ottoman delegation. Thus, the earlier date could commemorate the time of the original likeness prior to its production as a print. Further analysis of these prints, deeper studies by Rasmussen, are cited in References.

In the absence of a summary biography other than Volume One or the 2023 catalogue, the next series of works receive more context discussion (pp. 269-313). In 1563 Maximilian made his ceremonial entry into Vienna, and Lorck received the commission to produce the public art, subsequently published as woodcuts by Donat Hübschmann in a commemorative volume. This extensive entry follows the procession and notes the locations of decorated ceremonial arches and wine-spouting wells, while showing the woodcuts and inscriptions as well as a pair of surviving Lorck drawings for the volume (1563,2; 1563,4). This commission reveals the artist’s continuing high-level imperial connections, cemented by a woodcut of the family coat of arms (1564,1) after renewal of Lorck’s patent of nobility.

Relocating to Hamburg by 1567, Lorck surveyed the Elbe River and produced a twelve-meter-long map (1568,1) along with a design for a lost city gate (1568,2). Preoccupation with Turks took several forms, including a hostile song pamphlet associating the Sultan with the Antichrist (1568,3 with text), but also woodcuts of mosques and other buildings in the Ottoman Empire for the Turkish Publication (1570; Volume Three, pp. 31-60, nos. 3-14). Particularly striking is the depiction of Süleyman’s signature mosque complex with an ominous sky, where a comet and dark clouds dispel the crescent moon of Islam. During the period 1569-73, Lorck focused on Turkish costume studies (1569,4-1573,2), which align with contemporary ethnographic fashion books produced across Europe.[1] These seventeen ink drawings feature bold linear networks ready for translation into woodblocks for printing, suggesting a developing ambition to realize the Turkish Publication. Lorck also reissued expanded, full-length engravings with backdrops of his previous portraits of both the sultan and Persian ambassador (1573,3-1574,1)

Perhaps in pursuit of his ambitious project, Lorck then moved to Antwerp, Europe’s publishing capital, in 1574; however, his timing was terrible, since 1576 saw the city at its political nadir with a destructive sack by Spanish troops. But during his stay, he did add a drawn emblem folio to the album amicorum of famed geographer Abraham Ortelius (1574,5), a rocky bluff with a ring at its summit, beset by waves below and winds above. Its Latin inscription is translated and includes Lorck’s own motto, “God my helper and protector.” Also in Antwerp, he made a profile portrait in a roundel of learned historian and numismatist Hubert Goltzius (1574,4), on which he copied the inscription from Philips Galle’s earlier portrait of the sitter. He also designed Gospel woodcuts for a Catholic missal, produced by the great publishing house of Christophe Plantin (1574,6-1574,10; the blocks are still extand in the Plantin-Moretus Museum).

Significantly, a title page woodcut for the Turkish Publication emerged with a complex set of roundels, including Lorck’s motto and emblem from the Ortelius album and a profile self-portrait. Oddly, the bottom of the page features accurate letters of both Greek and Hebrew but only as alphabet rosters rather than learned epigrams. The inscription around the self-portrait offers a date of 156[7], suggesting that the design had an earlier origin before Lorck’s Antwerp move. Woodcuts began to be produced, possibly beginning in Antwerp, but with an eye toward publication in Frankfurt with Sigmund Feyerabend, who published the Lorck coat of arms in a translated anti-Turkish tract in 1577. More on this publisher, who used images by Jost Amman, would be a desirable research agenda for a historian of the book. Overall, the years 1581-82 saw production of 79 woodcuts and the virtual cessation of all other Lorck activities. As noted, those realized woodcuts are already catalogued by Fischer in Volume Three. A final woodcut excerpts a female Turkish harpist (1583; Vol. Three, no. 126) from one of Lorck’s earliest Constantinople drawings (1555-59,2).

However, the artist finally became a salaried court painter to Danish king Frederik II, for whom he made several works: a woodcut emblem of the royal Order of the Elephant (1580,1), featuring a profile of the king and his coat of arms on the elephant and castle image; a full-length, armored, standing court portrait painting on canvas (1581, 1; Hillerød, Frederiksborg Castle); and a 1582 oval portrait engraving (1582, 1).

Despite the non-finito tragedy of this peripatetic Dane’s artistic career, enough of his work survives to reveal both his great ambition and significant accomplishments. Though never fully attached to any single court, his elite associations (and pretensions) enabled him to cross boundaries and bring back imagery from distant Constantinople and to contribute to European royalty with portraits and entries. Unlike Lorck’s own truncated projects and that of his devotee Erik Fischer, his entire oeuvre can now be viewed in its entirety with both fresh thinking and scholarly rigor, thanks to the dedicated efforts of Bencard and Rasmussen in the footsteps of Fischer. Long before the great flowering of Danish art after 1800,[2] cosmopolite Melchior Lorck of Flensburg had already given his nation art historical significance.

Larry Silver

University of Pennsylvania, emeritus

[1] Margaret Rosenthal and Ann Rosalind Jone, The Clothing of the Renaissance World: Cesare Vecellio’s Habiti Antichi et Moderni (London, 2008); Ursula Ilg, “The Cultural Significance of Costume Books in Sixteenth-Century Europe,” in Catherine Richardson, ed., Clothing Culture, 1350-1650 (Aldershot, 2004), 29-48. Pages from costume books by Hans Weigel (1577) and Abraham de Bruyn (1581) appeared in the 2023 Copenhagen exhibition.

[2] Freyda Spira, Stephanie Schrader, and Thomas Lederballe, Beyond the Light: Identity and Place in Nineteenth-Century Danish Art, exh. cat. (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2023).