In German art, the question a “Northern Renaissance” and when (or if) it occurred usually centers around such turn-of-the-epoch figures as Albrecht Dürer and the magic year 1500. Moreover, dominant urban centers like Augsburg and Nuremberg or court centers dispersed across the Holy Roman Empire focus our attention on geographical crossroads more than marginal provinces. Finally, the modern museum bias towards painting often neglects sculpture as a leading, costly medium.

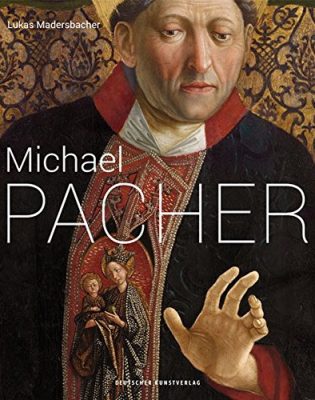

Thus a figure like Michael Pacher (c.1435-1498) merits renewed close attention. While not unknown or unstudied, Pacher stems from a corner region, Südtirol, dates from the later fifteenth century, and works primarily in sculpture but with a major contribution to spatially constructed paintings. This beautiful new monograph reopens the assessment of Pacher with lavish illustrations and careful analysis, and as his subtitle suggests, Madersbacher sees the artist as transitional between both era and regions. The author, a professor at Innsbruck’s Leopold-Franzen University and co-editor (with Paul Naredi-Rainer) of the two-volume Kunst in Tirol, is ideally placed to assess Pacher’s artistic significance.

To some extent, this complete survey of Pacher revisits the monograph (1969; English ed. 1971) by Nicolò Rasmo and the Pacher exhibition and symposium by Artur Rosenauer (1998-99), but with a systematic catalogue and high production values, including beautiful color close-ups. In some respects, the book offers a conventional life-and-works structure, beginning with a thorough biographical essay, which features the cultural geography of Pacher’s hometown guild city (since 1462/63), Bruneck im Pustertal, and its bishopric of Brixen, featuring Nicolaus Cusanus, later Pope Pius II (1458-64). The more shadowy figure of painter Friedrich Pacher, probably from Neustift, appears briefly; he surely collaborated with Michael on several projects, especially mural works. But Michael’s own main formation came from northern Italy, specifically Mantegna’s Padua, and Madersbacher asserts that he encompassed skills in both sculpture and painting, Doppelbegabung, but surely through a large workshop. As is the case with Bernt Notke in Lübeck, at the opposite end of the Empire, sorting out the actual role of the lead artist/entrepreneur remains a major question.

Madersbacher brings his extensive familiarity with Tyrolean fifteenth-century art to present the regional setting and influences out of which Pacher’s art grew, notably the unheralded Master of Uttenheim (also plausibly assigned a reconstructed ensemble of wings around the central Coronation of the Virgin, Munich; fig. 95, formerly – more persuasively – assigned to Pacher himself). From Padua he singles out Francesco Squarcione along with Donatello’s Santo reliefs and Mantegna’s Ovetari Chapel (with Nicolò Pizzolo) for both figures and perspectival space. These nuance the more familiar sources of Pacher’s innovations but also reinforce crucial artistic formations from Italy, already evident in the Saint Lawrence Altarpiece (c.1465; Munich). A surprising influence claim, especially for sculpture, stems from the Upper Rhine in works by Nicholas Gerhaert in Strasbourg.

Pacher’s emphatic early perspectives are revealed here as “distance-point” or “bifocal” construction, already found in the Master of Uttenheim, but later he adopts a central perspective, attained through mathematics according to Madersbacher as well as Mantegna (San Zeno Altarpiece, Verona), and already visible in his Church Fathers Altarpiece (1470/78; Munich) but climaxing in the painted panels of the celebrated Saint Wolfgang Altarpiece (1475/81; in situ), where portal frames before deep spaces dissolve the boundaries between viewer and viewed. In the late Salzburg Altarpiece (before 1498), preserved in fragments (Vienna, Belvedere), Pacher pursues a more intimate, intersubjective figural narrative. A later section (95 f.) will correctly downplay earlier loose links of such pictorial efforts to the 1453 Cusanus tract, De visione dei (pace Peter Thurmann 1987 as well as Belting and Wolf, briefly), but the author does acknowledge this critical shift to “perspectivity.”

Madersbacher also traces Pacher’s sculptural shrine development from Gries (1471/75) through Saint Wolfgang (Salzburg is too fragmented), emphasizing their consistent adherence to a hieratic, blocky, cultic conventionality over Pächt’s suggestion of enhanced pictorial illusion. Nevertheless, as many have noted, glittering highlights flicker optically across the preserved St. Wolfgang ensemble, almost dissolving the Schrein itself. Saint Wolfgang thus remains a unique, if climactic ensemble.

However, Madersbacher, cautions (96-101) against the anachronism of viewing that work as a Gesamtkunstwerk, pointing out instead, following Klaus Lankheit, profound tensions – which he regards as “fruitful conflicts” – inevitably inhere in any Schrein that already involves perspectives, and in multiple individual spaces at that. Media self-consciousness seems baked in (citing Marius Rimmele, Deas Triptychon als Metapher, Körper und Ort, 2010). The resolution to this dilemma finds its form in the painted illusion of a shrine, much like Pacher’s own (much smaller and closable; space analyzed, 102-03) illusionistic Neustift Church Fathers ensemble, but carried further in Tyrol through the art of Marx Reichlich and Friedrich Pacher (plus the Master of Uttenheim’s dismembered name work; fig. 94). Indeed, “mediality” and “aesthetic difference” as themes (as in work by Klaus Krüger, Das Bild als Schleier des Unsichtbaren, 2001) serves as a marker of self-conscious pictorial purposefulness in Pacher’s religious art through stone frames and portals as both boundaries and thresholds. With Otto Pächt, he also sees a distancing self-consciousness about medieval conventions, especially in the late Salzburg retable (107-17), a “dialectic between innovation and retrospection.”

While this monograph will not definitively sort out “Groupe Pacher,” whether Friedrich Pacher, the Master of Uttenheim, or other anonymous associates revealed in its exquisite details, it does thoughtfully discuss the state of research (304-23, including the profile court portrait of Mary of Burgundy, Kisters Coll., fig. 331). It carefully reconstructs (in color) the dismembered segments of lost ensembles, such as the St. Lawrence Altarpiece (c.1465, pp. 127-43). In addition, frescoes are included and fully illustrated in color, often with details, and related to appropriate panels or sculptures from the same site (e.g. Kloster Neustift). Rosters of Lost Works (302-03) and Documents (328-44) are appended.

Both author and publisher deserve our warm thanks for making this the book to consult today for any thoughtful Pacher research.

Larry Silver

University of Pennsylvania