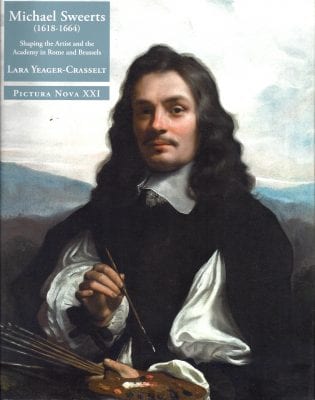

Modern scholarship has routinely presented the Brussels-born Michael Sweerts as an ally of the Bamboccianti, those mainly Netherlandish genre painters in Rome notorious for disregarding conventional Italian artistic standards. In her meticulously researched and lucidly written book, Lara Yeager-Crasselt focuses instead upon Sweerts’s important ties to traditions of academic classicism. As she explains, her book seeks to explore “the enduring and fundamental influence of the Italian academic culture” (14) that Sweerts experienced in Rome and in his native Brussels, and “to establish Sweerts’s role in … defining the formal set of academic and classicist ideas that emerged in the Netherlands in the seventeenth century.” (24) After outlining her mission and findings in the introduction, the author makes her case in four densely packed chapters, a brief conclusion, appendices transcribing unpublished and little-known documents, and copious, informative endnotes.

Yeager-Crasselt demonstrates that Sweerts’s exposure to classicism began in the painter’s native Brussels. Home to the Habsburg court in the Netherlands, the city attracted numerous painters well versed in Italian and classical artistic ideas during the painter’s formative years. Masters active there such as Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640), Gaspar de Crayer (1584-1669), Antoon Sallaert (c. 1580-1650), Wenzel Coeberger (1560/61-1634), and Theodoor van Loon (1582-1649), maintained close ties with humanists, copied after ancient sculpture, and regularly infused their paintings with classical elements. Although no direct personal links with Sweerts can be identified, their work “established the larger pictorial vocabulary that Sweerts would have known” as a developing painter (33). His familiarity with classicizing art in Brussels gave Sweerts “a different…artistic sensibility from other artists who belonged to the Bamboccianti” (51), enabling him to arrive in Rome receptive to the dominant local artistic culture.

During his sojourn in the ancient capital – documents place him there from 1646 to 1652 – Sweerts appears to have spent as much time engaging with members of the Roman Accademia di San Luca as he did with his colleagues in the Netherlandish Schildersbent. Early in his stay he helped to serve the interests of the Accademia, collecting money owed by the Bentvueghels for payment to the Roman authorities. Soon afterwards, he entered the employ of Camillo Pamphilj, nephew of the reigning pope, probably for the purpose of acquiring works of art for the family collection. He also seems to have taken part in an “Accademia de Pittori” that, Yeager-Crasselt importantly establishes, met for at least several years in the Pamphilj palace. As the author reminds us, Sweerts’s paintings of the period reveal a lively interest in the art of classicizing masters. More than one of his works feature depictions of statuary designed by François Duquesnoy (1597-1642), the noted Flemish expatriate in Rome credited with having imitated the Greek manner. Other paintings expose Sweerts’s fascination with the style and teaching of Nicolas Poussin (1599-1664).

Back in Brussels, Sweerts founded c. 1656 “een accademie van die teeckeninge naer het leven” that reflected in part the teaching of the Roman Academy and other Italian academies of art while also taking the measure of earlier Dutch academic models. Artists’ academies had previously existed in the Dutch Republic but none had arisen in the Spanish Netherlands prior to that time. Sweerts’s efforts began a tradition of academic art pedagogy that continued in Brussels and the surrounding region.

That Sweerts engaged deeply with the classical tradition throughout his artistic career seems beyond dispute. The extent to which Sweerts endorsed the theory of art promoted by his classicistic colleagues remains less certain, however. Sweerts produced mainly small canvases populated with figures from the lower social orders, precisely the kind of works that classicizing painters Francesco Albani (1578-1660) and Andrea Sacchi (1599-1661) reportedly considered to be their art’s ultimate degradation Moreover, Sweerts did not idealize nature to the degree championed by Poussin and other classically oriented painters in Rome. His artistic choices left Sweerts open to the same type of negative criticism that classicist Giovanni Pietro Bellori leveled at Il Bamboccio: that he was a Peiraikos unsympathetic to the beautiful idea.

Sweerts’s paintings representing artists at work, which the author holds to have “evoked the traditions of artistic education that the Accademia de San Luca advocated” (53), seem more ambiguous in their theoretical stance than Yeager-Crasselt allows. The master’s fascinating Painter’s Studio in the Rijksmuseum (Pl. 17) distances itself from its purported model, Odoardo Fialetti’s etched Artist’s Studio of 1608 (Fig. 21), by featuring fragmented plaster casts piled haphazardly on the workroom floor. Rather than serving as revered subjects of study as in the Italian print, the famed ancient models in Sweerts’s piece receive an indifferent response from the room’s inhabitants. Similarly, Sweerts’s Roman Street Scene in Rotterdam (Pl. 14) shows a young draftsman sketching after a modern sculpture, one by the idiosyncratic Gianlorenzo Bernini no less, seemingly oblivious to the ancient remains and classically-posed contemporaries in his midst. Yet another painting (Pl. 38) shows a draftsman sketching an old beggar, clearly preferring that lowly present-day subject to the carved ancient capital tumbled at his feet. These works suggest Sweerts’s attitude toward the pedagogy of his classicizing colleagues to have been well short of straightforward appreciation. Il Bamboccio and his followers in Rome also engaged deeply with the classical tradition, referencing ancient sculptures and classical iconographies in their paintings in ways that seem to subvert the dominant culture and claims of classical superiority. Such considerations may speak in favor of situating Sweerts in the context of the Bamboccianti after all. Any future examination of the matter will have to take full account of the arguments put forth in Yeager-Crasselt’s important book, however.

David A. Levine

Southern Connecticut State University