Joanne Anderson expands our knowledge of Mary Magdalen imagery by analyzing little known Alpine fresco cycles and altarpieces of the saint produced between the late thirteenth and early sixteenth century. Located in modern-day Italy, Switzerland, and Austria, these paintings emphasize different aspects of the saint than those found in the more widely published cycles, often located within mendicant contexts, in cities such as Florence, Assisi, and Naples. In this revision of her 2009 doctoral dissertation, “The Magdalen Fresco Cycles of the Trentino, Tyrol and Swiss Grisons, c. 1300-c. 1500” (University of Warwick), Anderson notes these Alpine cycles appear in churches simultaneously catering to local, rural parishes as well as to pilgrims traveling to major cult sites in Provence, Santiago, or Rome. Anderson offers close readings of these works within their Alpine context, emphasizing the ways in which their content reflects both a more universal or international outlook on the Magdalen, particularly relevant to the pilgrims passing through on major transit roads crisscrossing the Alps, yet also responds to the more insular needs of the local communities. For Anderson, the Alps offer not a boundary but rather an exchange network, with pathways connecting people, artists, and ideas. While developing this perspective on Alpine art, she focuses on seven major sites, using them to consider questions concerning the effects on the artwork of its natural surroundings, devotional and cult practices in rural communities, communal and aristocratic patronage, and the functioning of itinerant painting workshops.

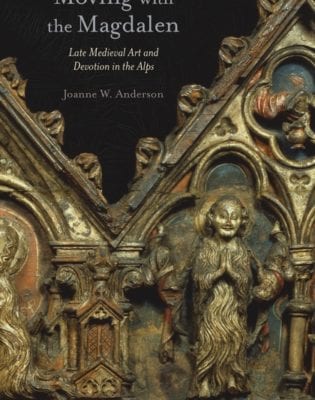

Following her “Introduction,” Anderson uses Chapter One to analyze the rarely discussed Carema Altarpiece (c. 1295; Turin, Palazzo Madama-Museo Civico d’Arte Antica), attributed to the itinerant Oropa Master and workshop, active in the Piedmont and Aosta Valley. The now fragmentary altarpiece originated in Carema, a town situated along the Via Francigena north of Turin and close to Provence, location of the most significant Magdalen cult sites. Anderson draws on the disruptions to the Magdalen cult occasioned in December 1279, when Charles II of Salerno claimed the Magdalen’s body had not been removed to Vézélay in the eighth century, but rather remained in Saint-Maximin-la-Sainte-Baume in Provence. Her relics, in a fourth-century early Christian sarcophagus, were ratified by Pope Boniface VIII in 1295. Anderson argues that the Carema Altarpiece’s unusual form and its narrative program reflect this recent reinvigoration of the Magdalen’s cult by linking it to the newly authenticated site of her relics. She concludes the altarpiece, a most unusual gabled structure with sculpted narratives in two registers subdivided by architectural elements, recalls the early Christian sarcophagus housing the Magdalen’s relics and so becomes a “preparation for, remembrance of or substitution for the original shrine in a wider imagined community of devotion” (34). The altarpiece’s eight extant narratives, equally split between traditional Gospel scenes and those illustrating her legendary stay in Provence, serve as surrogates for local viewers while allowing pilgrims to anticipate or recall their site visits.

Chapter Two turns to a mid-fourteenth-century fresco cycle located in Sankt Maria Magdalena in Dusch (Switzerland), attributed to the Waltensburg Master. Here again Anderson argues for both local ties and universal elements of interest to travelers. Regarding the former, Anderson identifies the kneeling monk in Mary Magdalen in the Wilderness as a Premonstratensian, and so connects the cycle to the nearby monastery; this further prompts her to consider the saint within the context of the Premonstratensian Order’s “semi-monasticism” (56) and its commitment, like the Magdalen’s, to both active and contemplative lives. Less convincingly, Anderson suggests the image of an angel bringing the saint a basket of bread instead of the usual host allowed both laity and pilgrims to identify with the basket’s ordinariness. Additionally, she notes the first two scenes – The Raising of Lazarus and The Anointing at the House of Simon the Pharisee – are reversed chronologically. Offering several explanations, she wonders if the artist has conflated The Anointing with The Anointing in Bethany. I suggest this raises interesting issues for further consideration, including possibly identifying the figure with the pointed hat as not Simon but Judas, when he accuses the Magdalen of wasting money better given to the poor (John 12:1-8).

Subsequent chapters continue to link the cycles to local contexts, as well as to distant pilgrimage sites. Chapter Three turns to Sankt Magdalena in Prazöll, outside of Bozen (South Tyrol). Although locally performed mystery plays influenced the iconographical handling of the narrative, as Anderson proposed in an earlier publication, here she also ties the Magdalen to St. James the Greater and larger devotional pilgrimage networks. An essential connection between all these Alpine sites and the Magdalen is formed by the act of pilgrims and laity ascending through the mountainous landscape, experiencing hardships similar to the Magdalen’s in Provence. In Chapter Four, Anderson proposes that the frescoes in Sankt Oswald, Seefeld (Austria), also replicate pilgrims’ experiences at the Magdalen’s mountain grotto and tomb in Provence, and so assure viewers of her real presence in the Tyrol. Yet at the same time, Anderson notes ways the cycle connects the Magdalen to a Maundy Thursday host miracle that occurred in Sankt Oswald in 1384. The somewhat unusual choice and handling of scenes – including a Mary Magdalen Anointing Christ’s Feet that looks more like a Last Supper – heighten references to the Eucharist, penitence, absolution, and redemption, themes significant to the miracle story itself.

Chapter Five’s discussion of Matheis Stöberl’s 1509 Magdalen Altarpiece for the saint’s church in Mareit (South Tyrol) integrates the work into the context of mining, an important local industry. Anderson explains that, while not the patron saint of miners, the Magdalen experienced thirty years of hardships in her rocky grotto and thus offered reassurances to those involved in this dangerous underground profession. However, throughout this chapter Anderson pushes too hard to find local connections; I found it the least satisfying analysis.

Chapters Six and Seven consider two unusually extensive late-fifteenth-century narrative cycles, in Santa Maria Maddalena, Cusiano (Trentino), and Sankt Maria, Pontresina (Switzerland). Anderson places the Cusiano cycle, by the Lombard Baschenis brothers and shop, within the context of its location on an important transit route, one allowing influences from a variety of sources: migratory artists’ workshops, itinerant players, and local preachers. Mixing standard iconography with innovative treatments in this thirty-scene Magdalen cycle, the Baschenis brothers represent a highly successful if not highly skilled itinerant workshop that moved widely around the Alpine districts, recycling stock imagery as needed. The cycle of eighteen (possibly nineteen) scenes at Pontresina, also by a north Italian itinerant shop, proves more innovative, as Anderson ferrets out complex imagery related to fears regarding pregnancy, childbearing, and redemption. In a church originally dedicated to the Virgin Mary but rededicated to the Magdalen and celebrating her extraordinary powers of intercession, the frescoes challenge viewers by their unusual arrangement and iconographical modifications. Anderson’s analysis offers a satisfying account contextualizing the Magdalen cult relative to local resurrection sanctuaries and issues especially important to local women.

Overall, Anderson has contributed significantly to Mary Magdalen studies. The strengths of her book lie especially in achieving her goal of characterizing what is “Alpine” regarding these seven manifestations of the Magdalen cult. Her in-depth treatments unify them within this region of transit while distinguishing them from each other and from the better known central Italian cycles explored in depth by earlier scholars. By considering the Alpine cycles within their mountain context, she successfully explores their significance not just for local parishioners but also for pilgrims undertaking difficult Alpine travel. Each chapter is richly documented through extensive endnotes and a generous bibliography. Illustrations of these images are not easily available, and thus the figures and color plates (largely Anderson’s own photography) are invaluable.

The book could profit from expanding Anderson’s consideration of this region as a place of transmission to include possible French sources. For example, although she claims that the c. 1280 Accademia panel of the Magdalen offers the earliest scene of the saint’s funeral (125), artists at Chartres Cathedral had earlier depicted that narrative in stained glass (bay 46). Further, Anderson’s arguments sometimes rely too much on speculation – “possibly” and “probably” appear far too often – and there are errors needing correction: for example, the meanings of “terminus post quem” and “terminus ante quem” are erroneously reversed (58, 198); the Golden Legend does not name the hermit priest Zosimus, as claimed (63); and in the Legend, the Magdalen places the sign of the cross on the pilgrims’ shoulders, not their backs (84). Anderson’s editor also bears some responsibility for not correcting a variety of grammar and punctuation errors, typos in endnotes, and incorrect figure and plate numbers within the text. More significantly, the book would benefit from larger photographs, to make many details Anderson discusses easier to see; a more detailed and useful index; and a map not just indicating the routes through the Alps (Figure I.1), but also locating the seven discussed sites.

Penny Howell Jolly

Professor Emeritus, Skidmore College