It must have been one of the most satisfying and challenging tasks with which a museum curator can be faced. To be presented with six of the finest pictures ever executed, namely Titian’s poesie carried out for King Philip II of Spain, and to have to decide how to display them. Whether, as the National Gallery in London did, to hang them alone in a single gallery, so that the impact of the art of painting was delivered to the spectator with the force of a sledge-hammer, or, as the Museo del Prado in Madrid, taking into account the enormous riches of their permanent holdings, has chosen to do by making them the center of an exhibition which presents a feast of mythological paintings. Needless to say each in its own way was equally rewarding and memorable.

To create an appropriate atmosphere the Prado exhibition begins with a Roman sculpture after a Greek original of Venus of the Dolphin (1) and a page showing a lewd satyr and a sleeping woman from the Hypnerotomachia Poliphili (2). Thereafter it is composed of twenty-seven paintings just over half of which belong to the Prado, augmented by some distinguished loans. To accommodate the theme there is some diminution in painterly quality on display by the inclusion of copies after Parmigianino’s Cupid (3) and Michelangelo’s Venus and Cupid (5), but otherwise the works are almost exclusively of the highest quality. Titian’s six poesie are augmented by four other works by him, including the Prado version of Danae (13), sometimes, but not here, regarded as the version belonging to the set of poesie, and The Worship of Venus (7) and Bacchanal of the Andrians (8). Matched with Titian’s version of the subjects (14 and 16) are two outstanding works by Veronese of Venus and Adonis (15) and Perseus and Andromeda (17).

Given Titian’s enormous influence on the seventeenth century the exhibition meaningfully continues with works by Poussin, The Hunt of Meleager (23) and Landscape with a Thunderstorm with Pyramus and Thisbe (24), Ribera, Venus and Adonis (25), a picture which is flattered by the company it keeps, and Van Dyck, Venus at the Forge of Vulcan (26), and, exemplifying that last effusion of brilliance by the artist, Cupid and Psyche (27). With its depiction of a tapestry representing Titian’s Rape of Europa in the background, Velázquez’s The Fable of Arachne or The Spinners (22) was a particularly appropriate exhibit. With six paintings of the highest quality, Rubens was in danger of becoming a rival to Titian. How well the two painters were in harmony of spirit was demonstrated by hanging Rubens’s Garden of Love (9) opposite Titian’s The Worship of Venus (7) and Bacchanal of the Andrians (8).

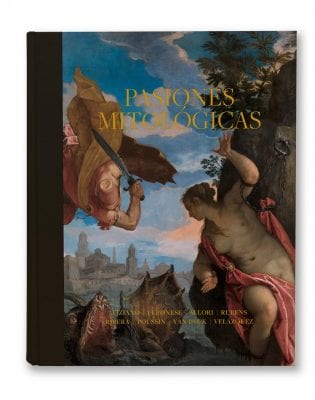

For those in these covid-ridden days who were denied the opportunity of seeing the exhibition, the excellent generously illustrated catalogue provides some recompense. It begins with three well informed articles. In his essay, “Titian and the Poesie: Experimentation and Freedom in Mythological Painting,” Miguel Falomir explores the art historical context. As a starting point he takes Titian’s Venus and Adonis, observing that its precise subject, Venus in the act of restraining Adonis, was a new subject, not to be found in classical or modern literature, leading on to different interpretations by Veronese and Ribera. In his contribution Javier Moscoso provides a philosophical interpretation of “Painting the Passions.” Sheila Barker in her essay “Andromeda unchained: Women and Erotic Mythology in Renaissance Art, 1500–1650” offers the feminist perspective. What she brings out, inter alia, is the contrast between the outrage expressed by the suffragette movement at the beginning of the last century over such images of female nudity as Velázquez’s Rokeby Venus, leading to its slashing, and the complicity shown by female painters and patrons of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries in their attitude to mythological nudes, both male and female. In Lavinia Fontana’s unredeemably titillating painting of Mars and Venus, the god is about to grasp the goddess’s bottom, while Isabella d’Este filled, albeit with a moralising purpose, her studiolo in Ferrara with mythological paintings.

When it comes to the discussion of individual works in the exhibition, which forms the major part of the catalogue, Alejandro Vergara eschews the conventional catalogue entry in favor of what he calls “Passionate and erudite commentaries on twenty-nine works of art that deal with love and desire,” taking the term commentary from literary criticism. He addresses what we see, what we know and, especially, what thoughts the work in question provokes. The tone is engagingly personal and conversational, and with plentiful free thinking his writing makes for lively and stimulating reading. Learning is worn lightly but the essential art historical information is there.

As an example of felicitous thoughts, one may pick out the contrast he draws between Titian’s rendition of Diana in his Diana and Callisto (19) and Rubens’s treatment of the same subject (20). Whereas in Titian’s painting, “the lack of empathy and mercy shown towards the nymph Calliso is shocking,” “Rubens’s staging of the story,” bearing in mind its relevance to his personal life with Helena Fourment, “makes me feel that when she [Diana] does [i.e. excoriate Callisto], it is against her heart.” When it comes to that gender fireball, Titian’s Rape of Europa (21), he touches sensitively on the feminist issues which arise.

As Falomir points out, Titian’s poesie and other mythological works have in recent times been interpreted from a number of different ways, namely “philosophical, astrological, psychoanalytical, christological, mnemonic, and above all political,” but none of such readings were applied to the works at the time. Yet what can be deduced from various contemporary sources is that the appreciation of the erotic element in such stories played a major part, which provides the underlying theme throughout the catalogue, even down to alluding to personal details of Titian’s life. Although denied by the painter, his agent claimed that the delay in delivering The Andrians may have been because “the girls that he often painted in different poses arouse his appetite, which he then satisfies more than his delicate constitution permits.” The Prado show is a glorious manifestation of sex and sensibility expressed through the medium of mythological painting.

Christopher White

London