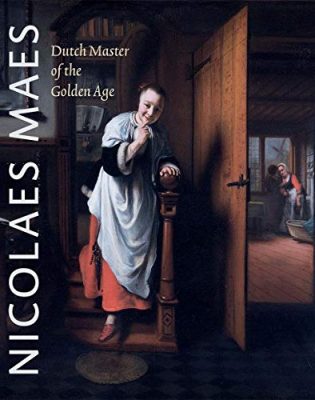

This concise, well-illustrated catalogue was published to accompany the first monographic exhibition devoted to Nicolaes Maes (1634-1693), presented in The Hague from October 17, 2019 to January 19, 2020 and in London from February 22 to September 20, 2020 (closed until July 8 due to Covid). I saw the show in The Hague, where Maes’s glowing canvases filled the intimate exhibition rooms on the upper level of the Mauritshuis. Although limited to thirty-five paintings, the installation deftly presented the high points of Maes’s career. At the National Gallery, drawings were also featured. In the book, thematic essays by Ariane van Suchtelen trace the diverse aspects of Maes’s development. Each painting receives an individual entry (written by Van Suchtelen, Bart Cornelis, or Nina Cahill), but drawings exhibited in London are signaled only by notes in the image captions. An essay by Marijn Schapelhouman surveys the artist’s graphic oeuvre, which oscillated between quick compositional sketches in pen and ink and sensitive figure studies rendered in sharp red chalk. Schapelhouman makes a case that most or all of the seventy-five sketches dubbed by Werner Sumowski “the pseudo-Victors group” should be attributed to Maes. This includes at least one atmospheric landscape drawing (fig. 10, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam; exhibited), further expanding the artist’s range.

Biographical details are summarized in a timeline. Following basic training in Dordrecht, Maes apprenticed with Rembrandt around 1646–52, specializing in dramatic history paintings such as Abraham’s Sacrifice (cat. 3, Kingston, Agnes Etherington Art Centre). By 1653, he had returned to Dordrecht, where he became a highly original painter of genre subjects. He also began to paint portraits, soon turning to this specialty full-time. In 1673 he moved to Amsterdam, where he died twenty years later.

The exhibition surveyed all phases of Maes’s work, but it could not present his career with proportional accuracy, since extant paintings comprise fewer than ten history subjects, around fifty genre scenes, and over seven hundred portraits. Domestic genre paintings – long considered Maes’s prime achievement – formed the heart of the show. The installation brought together four of the six “eavesdropper” scenes for which Maes is best known (cat. 16, Royal Collection, London; 17, Wellington Collection, Apsley House; 18, Mansion House, London; 19, Dordrechts Museum) alongside engaging images of families, maids, needleworkers, and old women dozing over a book. The catalogue handles iconographic analysis with a light touch that seems appropriate for these gently humorous vignettes, nearly all completed within a span of four years (c. 1653-57).

The artist’s family may have modelled for Young Mother with her Children (cat. 14, Thyssen, Madrid), one of Maes’s most charming genre scenes. Provenance suggests that it was once part of a series referencing the five senses. While the catalogue entry reconstructs the series, only Young Mother was exhibited, perhaps with good reason. As a whole, the group gives a fuller picture of Maes’s concerns as a genre painter, but not a completely appealing one. Man Holding a Carnation to a Woman’s Nose, or, Allegory of Smell (fig. 14c, Oxford, Ashmolean Museum) presents a stilted encounter between a mismatched couple that may be described as glamorously creepy. It is one of a number of relatively contrived outdoor genre scenes in which Maes seems to push the limits of his capabilities as a storyteller. This aspect of his oeuvre is represented in the exhibition only by a relatively sympathetic pair of paintings depicting a country milk seller (cat. 20, Guildhall Art Gallery, London) and a city maid stopping to gossip on the way home from the fish market (cat. 21, RCE Cultural Heritage Agency). While it is likely, as the authors argue, that Maes turned to portraiture because it offered greater financial security, perhaps his interest in genre had reached a dead end.

It was entirely as a portraitist that Maes’s first biographer, Arnold Houbraken, esteemed him, praising his fluent brushwork and talent for capturing likeness. As a classicist, Houbraken approved of Maes’s evolution away from Rembrandt, noting that “young ladies take more pleasure in white than in brown.” Yet, Maes’s rich tonalities and velvety touch remained indebted to Rembrandt. Van Suchtelen estimates that at the peak of his career in Amsterdam, Maes completed two or three portraits a week. One might expect that, like other successful portraitists, he engaged assistants, yet technical examination has revealed no trace of other hands. Instead, Maes kept up with demand by developing a standard repertoire of timeless costumes, pastoral accessories, and languid Van Dyckian poses that may reflect a trip to Antwerp. Indeed, he had already shown the ability to construct “variations on a theme” when developing his most successful genre motifs.

Today, compact bust and half-length portraits from Maes’s late period appear on the art market with astonishing frequency and at modest prices that reflect contemporary disdain for their repetitive elegance. In the exhibition, a few brilliant examples proved sufficient. A group of portraits of the Van Alphen family were reunited (cat. 30, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, 31–32, Galerie Neuse, Bremen, 33, priv. coll.), and several pastoral portraits in private collections were rediscovered, culminating in stunning pendants of an unknown boy and girl (cat. 24–25) and a family group relaxing in a palatial park (cat. 27). Such paintings are so far removed from the artist’s origins that early commentators theorized the existence of more than one Nicolaes Maes. Van Suchtelen’s survey of Maes’s fortuna critica traces this tradition while laying it to rest.

The catalogue gives some attention to issues of attribution and varying quality, but says relatively little about artists in Maes’s orbit. Van Suchtelen makes an argument for accepting Lot and His Family Fleeing Sodom, a large canvas that recently resurfaced at auction, as an authentic history painting of c. 1656-58 (fig. 13, whereabouts unknown, not exhibited). It is an ambitious work, but the tight cluster of large figures, each floridly accessorized, does not quite hang together. If this painting is by Maes, it seems more likely to date from the 1670s, as Werner Sumowski and Leon Krempel proposed. The archly solemn face of the daughter whose direct gaze centers the composition is as alluring as any of Maes’s classicizing portraits. Meanwhile, the catalogue dismisses Maes’s stepson, Justus de Gelder, as a minor talent, and four pupils identified by Houbraken, among them Margaretha van Godewijck, are mentioned only in a footnote. The timeline tells us that Maes and Jacobus Leveck, who apprenticed together with Rembrandt, became neighbors in Dordrecht and served together as lieutenant and ensign in the civic guard. One wonders if they might have shared artistic ideas as well. (Leveck specialized in portraits and figure studies.) However, these are tangential questions for future investigation. The catalogue is a thoughtful complement to a jewel of an exhibition, and it offers the first widely accessible overview of Maes’s work in English (as well as Dutch). As such, it makes a valuable contribution to the growing body of literature that treats Rembrandt’s associates as artistic personalities in their own right.

Stephanie S. Dickey

Queen’s University (Canada)