While this year marks a half-millennium of the Reformation, that story is limited by its German bias, to the neglect of the movement in Switzerland, which climaxed in Bern and Basel in 1529. One of the most versatile and influential figures other than the celebrated Ulrich Zwingli (1484-1531) was the painter-draftsman-author-soldier of Bern, Niklaus Manuel Deutsch (1484-1530). Appreciation of his artistry has suffered because so many of his paintings are still confined to his home town or even lost. In turn, his literary legacy is hampered by its presentation as occasional works, notably his drama, a satire on the Church, Die Totenfresser (1523), which unfolds through the ranks like his lost (but preserved in copies) Totentanz (I. pp. 186-246, nos. 19.1-24). Though widely celebrated for his larger Corpus of drawings, most of them still in Basel, Manuel can now be assessed fully as an artist through this long-awaited, systematic catalogue of his works.

The overview essay by Michael Egli presents Manuel in context (pp. 12-34), supplemented by the biography sketched by Petra Barton Sigrist (pp. 80-81), which clarifies his leading role in Bern civic politics after he suddenly abandoned painting in 1522 in response to the intense evangelical critique of religious images, including iconoclasm (one casualty of which was the Allerseelen-Altar donated by his own grandfather as recently as 1505; p. 17, figs. 4-5).[1] Egli traces the local history of city control over its parish church.

Manuel is documented best through a number of religious paintings. His altarpieces follow tradition and use ample areas of gold, but they also display an increasing fascination with physical space and with natural details (esp. in his Workshop of St. Eligius, patron saint of painters; cat. 3.03), but such elements would soon elicit critical reaction from contemporary religious leaders eventually including Manuel himself. His images of saints follow Matthias Grünewald (c. 1470-1528) in emphasizing vivid physical torments: The 10,000 Martyrs (cat. 6.01), Beheading of the Baptist (cat. 11), Crucifixion (cat. 12), and Temptation of St. Anthony (cat. 14.03), made for the Bern Antonite hospital retable One great contribution of this catalogue is the reconstruction of such altarpieces from their surviving fragments (cats. 2-3, 6-7, 14).

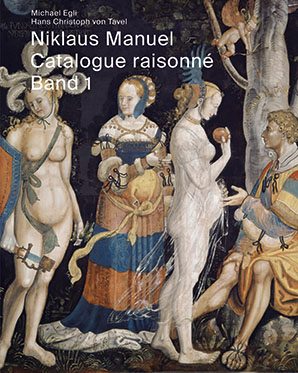

Occasional portraits include a self-portrait on parchment (cat. 16) and several anonymous men (cats. 5.01, 15). His murals include vault ornaments in the Bern Münster choir (cat. 17), and works only known from copies: the Noll House facade in Bern (cat. 18; a Power of Women theme, Solomon’s Idolatry) and the celebrated Dance of Death cycle in the Dominican cloister, destroyed in the seventeenth century (cat. 19; pp. 186-246). Manuel also painted several large-scale myths on canvas, notably Pyramus and Thisbe (cat. 4) and the better-known Judgment of Paris (cat. 13), both of which lament the consequences of desire.

However, Manuel’s decade-long creative career as an artist was dominated by drawing. He began with designs for stained glass, already an established pictorial tradition in Bern.[2] Along with Hans Holbein the Younger (c. 1497-1543) and Hans Baldung (c. 1484-1585), he was influential, a major innovator in that medium. In addition, one set of small silverpoint studies on wood (cats. 55.01-12) extends the practice of workshop modelbook patterns, Schreibbüchlein, as it includes two painted scenes about the Power of Women: Death and the Maiden and the World Upside Down (cats. 55.11-12). Two designs for stained glass capture subjects appropriate for the new, reformed religion: Christ and the Adulterous Woman and King Josiah Destroys the Idols (cats. 78-79).

Independent, finished drawings, akin to the works of Urs Graf (c. 1485-1528), survive as probably the most memorable Manuel creations. Often these are labeled with his own distinctive personal monogram, initials plus a Swiss dagger, like the drawings by Graf and Baldung. They feature fine, calligraphic linework in ink, often on prepared colored paper, like Altdorfer’s, presumably destined for a limited audience of connoisseurs.[3] One image, a Lucretia on wood (1517; cat. 9) resembles the drawings, as do the double-sided themes of Bathsheba and Death and the Maiden (1517; cat. 10). In similar fashion, some drawings on colored paper explore unconventional erotic subjects, especially female nudes in various roles. A recurrent theme in these private drawings is the fickleness of Fortune, whether in war, wealth, or women. Besides various satirical versions of the Power of Women, witches also appear in Manuel’s graphic works. Egli comments (p. 27) on profane elements in sacral subjects, such as the drawing, Madonna and Child (cat. 67). Only a pair of ink landscapes survive, towering cliffs (cats. 49-50).

Manuel also was adept with chalks and charcoal like Holbein the Younger. A pair of drawings in chalk depict Reisläufer, Swiss soldiers, like Graf. Many Manuel drawings were retained together, probably by the artist’s sons, and were soon inventoried in 1577/78 in the Amerbach Collection, whence they descended to the Basel Kupferstichkabinett. Prints are rare and most attributed ones are rejected here, except for the cycle of the Wise and Foolish Virgins (cat. 81).

These volumes, while costly, can be admired for their large-scale, accurate color reproductions and their (often generous) comparative images. One marvelous pair of pages (pp. 586-87) assembles Manuel’s monograms in chrono-logical order. Very useful are the essay on technical examination by Markus Küffner as well as the biography by Petra Barton Sigrist. The historiography of scholarship and exhibitions on the artist is discussed in an essay by Hans Christoph von Tavel, organizer of the great 1979 Manuel exhibition in Bern (pp. 35-51). Even more than most catalogues, this one offers added value for the extensive discussion of works rejected from the oeuvre (pp. 464-583), including one drawing (cat. R21; Basel) of a demon with an Ill-Matched Pair, a Swiss soldier with an old woman. The two volumes are beautifully produced; a lone annoyance is that the main exposition with its shorthand references in volume one remains widely separated from the bibliography in volume two. But in an era where publications of this kind are becoming extinct, this Manuel project, produced with generous subventions from the city of Bern and supported by both the city Burgerbibliothek and the Schweizerisches Institut für Kunstwissenschaft, is exemplary and will remain definitive.

Larry Silver

University of Pennsylvania

[1] Lee Palmer Wandel, Voracious Idols and Violent Hands. Iconoclasm in Reformation Zurich, Strasbourg, and Basel (Cambridge, 1995).

[2] Barbara Butts and Lee Hendrix, Painting on Light, exh. cat. (Getty Museum, 2000), esp. pp. 257-74. On his drawings, From Schongauer to Holbein, exh. cat. (National Gallery, Washington, 1999), pp. 327-43.

[3] Christopher Wood, Albrecht Altdorfer and the Origins of Landscape (Chicago, 1993), pp. 234-45.