In the Netherlands, the prosperous economic and cultural heights of the seventeenth century used to be called the “Golden Century” (Gouden Eeuw). But as if a veil has been lifted, recent revisionist thinking has revised that overweening positive sentiment and discovered hidden costs beneath that prosperity and creativity. To a certain extent, the ultimate blind spot of proud Dutch national consciousness was that nation’s leading role in the slave trade. Pioneering work in this revaluation, surprisingly, came through Dutch imagery of still life. Julie Berger Hochstrasser’s 2007 study, Still Life and Trade in the Dutch Golden Age (note the era still signalled by her title), focused on commodities, but it also managed to include enslaved humans among such goods as porcelains, spices, tea, tobacco, and sugar (the last named largely produced through enslaved labor, pp. 187-227). Since then scales have fallen from the eyes of Dutch historians and art historians, culminating in a prominent Rijksmuseum exhibition, Slavery (2021-22), which explored Dutch colonial slavery through ten true personal stories (enslaved people, owners, and resistors) that focused directly on Dutch involvement in the slave trade from the seventeenth through nineteenth centuries. In the meantime, several recent exhibitions have looked afresh at early modern imagery of Blacks: the awkwardly-titled Black is Beautiful. Rubens to Dumas (Amsterdam, Nieuwe Kerk, 2008); Revealing the African Presence in Renaissance Europe (Joaneath Spicer, ed., Baltimore: Walters Art Museum, 2012); Black in Rembrandt’s Time (Elmer Kolfin and Epco Runia, eds., Amsterdam: Rembrandthuis, 2018); and The Slave in European Art (Elizabeth McGrath and Jean Michel Massing, eds., Warburg Institute Studies and Texts, 2012).

To this accumulating collective vision the eminent art historian Angela Vanhaelen (McGill University) adds her penetrating analysis of seventeenth-century Dutch pictures that fail to equate Blackness with enslavement. Instead, that local imagery represents Blacks within both portraiture and scenes of daily life – a pictorial record of domestic prosperity. Vanhaelen reminds us of the Dutch pictorial and social inattention until almost the present day toward those slave-trading forts along the African coast that displaced those same individuals as well as toward the tropical plantations that provided the source of sugar and other commodities, already examined by Hochstrasser. Her argument is clear: Dutch paintings of Blacks compel complicity from their viewers by omission, and art history’s practices have failed to remedy that omission. Thus, the pictures and their modern interpreters have failed to represent “the trafficking of enslaved persons by masking the terrors of its operations, dehumanizing the captives, and endorsing the self-interested welfare of wealthy white mercantile elites who were the predominant investors in these kinds of paintings.” (p. 1) Viewers become situated pictorially within a social system of domination and subordination.

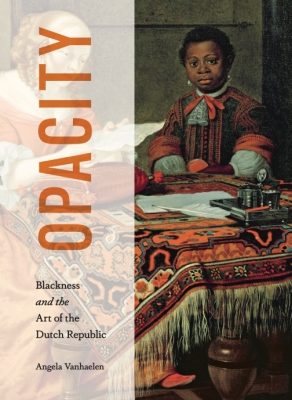

In her polemical book, Vanhaelen reframes the conversation on Netherlandish art by placing seventeenth-century domestic scenes and portraits in dialogue with images of plantations in colonial Dutch Brazil. She argues that Dutch paintings depicting enslaved Black Africans – such as Frans Hals’s neutrally titled Family Group in a Landscape (Madrid, Museo Thyssen Bornemisza) – not only obscure information about the institution of slavery but also fail to capture the resistance and dissent of people who did not conform to the anti-Black world imaged by Dutch art. Opacity aspires to spur its readers to grapple with that visual violence, performed in the very routinization of those paintings that show Dutch people with Black people in their midst, the product of what she calls “unfathomable crimes against humanity.” (p. 5) Her chosen title aspires to muddy the seeming transparency of Dutch realism’s seductive neutrality, and her Afterword makes the book’s goal explicit: “to undermine the authority and influence of these paintings by examining them in relation to historical evidence that gives the lie to their anti-Black agenda.” (p. 159)

By refusing to view Dutch pictures on their own terms, Opacity recognizes the historical privilege of sovereign positions and colonial domination, backed by both religion and local culture that eradicated oppositional alternatives. Vanhaelen proposes opacity as a methodology that concedes the fundamental impossibility of creating such alternatives. Her investigations thus resemble one recent creative reframing, shifting Mark Twain’s Black man Jim into Percival Everett’s James (2024); but they also gesture to the alternative Black world captured in the anthropologically informed South in Zora Neale Hurston’s 1937 novel, Their Eyes Were Watching God.

This book unfolds from a first chapter on Dutch social structure as founded on “unhomely secrets,” the privacy and sexual seclusion (promoting letters and attendant secrecy), permitted but also demanded for Vermeer’s household ladies, implicated in a gendered culture of domestic subservience. Vanhaelen draws this distinctly Dutch cultural structure in contrast to the extended economic and social (and sexual) freedom allowed their prosperous husbands, who participated in carnal trade abroad. Her profound chapter about Dutch patriarchal society within its art deserves attention from all interpreters of Dutch painting. Chapter Two focuses on Dutch pictures with young, “un-visible” Blacks in service to that same social system. Vanhaelen notes here that “Black bodies, too, are perceived as global commodities.” (p. 61) Similar points about the invisible costs of prized commodities were recently underscored for Spanish monarchs by Mónica Domíngues Torres’s Pearls for the Crown. Art Nature, and Race in the Age of Spanish Expansion (2024). Like the Amsterdam Slavery exhibition, Vanhaelen cites historical examples of sexual exploitation abroad and of enslaved individuals in Dutch cities.

The next discussion, “Displacement” (Chapter Three) ventures abroad to images of the displaced Blacks in the Dutch Brazil colony, a pictorial record also examined in Rebecca Brienen’s 2006 Visions of Savage Paradise, whose title surely records period Dutch ideology. In Chapter Three Vanhaelen focuses on the intentional inversion of maternal roles so esteemed in Dutch domestic ideology, by showing the colonial extirpation of family and gender identities through forced reproduction of slave populations by captive women.

A final large Brazil section, “necropastoral landscapes,” explores images showing plantations as fertile, verdant regions where Blacks are imbedded as elements of nature, much like medieval wild men or Amerindians as figured in nineteenth-century wilderness landscapes by Thomas Cole. Chapter Four analyzes Brazilian settings by Frans Post, who depicts enslaved peoples in “emotional apartheid” (p. 117) without cruelty or its resistance, but in recreation or as components of sugar mill work. While scarcely acknowledging the violence done to those humans or to the forested countryside (a “destructive worldview of conquest and extraction,” p. 129), these pictures coopt viewer complicity. Chapter Five attempts through earlier Post images is to present a positive image of how “enslaved people . . . at the edges of visibility” created their own spaces and social interactions, including vignettes of music and dance, while also noting how Post’s later images of church ruins convey anti-Catholic aspirations of Protestant colonial missions and their assurance that slavery was divine punishment for sinfulness.

Unlike Brienen, however, Vanhaelen neglects to attend to the native dwellers of the region, the Tupinamba, Tapuya, and other peoples who were displaced first by Portuguese and then by Dutch settlers to the region, who exploited the territory for its natural resources, beginning with brazilwood (which gave its name to the country rather than the reverse). Because her focus remains so firmly fixed on the displaced enslaved Blacks on Brazil plantations, she responds like the Portuguese in Brazil and the initial European colonizers who designated North America (including both her own Canada and this reviewer’s United States) to be a terra nullius, an uninhabited region, ripe for settlement and economic exploitation. In fairness, however, Vanhaelen does situate her own positionality.[1]

Ironically, in their production values Penn State’s book deliberately reproduces most of its images in black and white, thus further reducing the visible presence of their Black subjects. Especially in the Hals family group portrait, the very first illustration, a young Black servant blends into the tree foliage behind him. That, of course, is precisely Vanhaelen’s point, emphasized in her title, but reversed by contemporary painter Titus Kaphar, who singles out the staring youth and contrasts him by whiting-out his “family” (Fig. 2, in color). Familiar, color-filled Dutch paintings throughout the book appear colorless, except for chosen details of their Black figures. This book, polemical and explicit, visually attempts to undermine the foundations of Dutch enslavement, hidden beneath their comforting domestic imagery.

If a reviewer can be allowed a personal note, the experience of visiting actual remaining slave forts in Ghana, both Elmina and the Cape Coast Castle, on two different occasions becomes a vicarious visit into actual horror, combined with pious Dutch sanctimony (especially in Cape Coast’s chapel above the ground-level prisons). Like Vanhaelen’s well researched, revisionist book, it cannot remediate the past, but it can instill a permanent awareness of that past, something that all Americans as well as Dutch (and English and Portuguese and … ) should have to confront. In contrast to denials of history’s factual horrors currently promoted in US politics, this powerful book looks beyond the surface of its subject, familiar Dutch pictures, to suggest deeper, darker realities, human costs and suffering abroad that abetted those depicted comforts.

Larry Silver

University of Pennsylvania, emeritus

[1] Canada, she notes, settled lands “that were considered ‘vacant’ as federal and provincial governments moved Indigenous peoples onto reservations . . . Opacity accordingly proceeds from an acknowledgment of how my own experiences, perspectives, and opportunities are shaped by systematic inequities and policies that structure hierarchies of peoples for differential treatment.” (pp. 8-9)