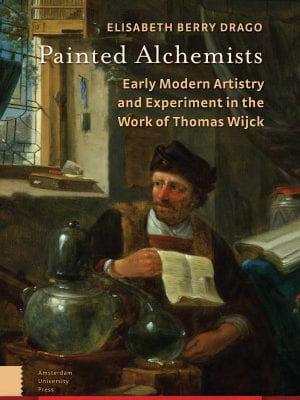

The interiors inhabited by the alchemists in the work of the Dutch artist Thomas Wijck (1616–1677) are fascinating and complex. Scattered with the tools and props of the alchemist’s trade, Wijck’s laboratories are messy spaces that privilege making and experimentation alongside creative enterprise and innovation. The alchemists who command these workrooms are not foolhardy or morally corrupt, but serious-minded, respectable individuals whose work was embedded in local and global exchanges of knowledge. Wijck’s paintings remind us of the parallels between the alchemist’s pursuit and the painter’s craft – how the grinding of pigments and mixing of solvents gave way to rich imagery of the visible world. The intersection of art and alchemy is reflected in the career of Wijck himself, an understudied artist who carefully built an artistic and professional identity around the depiction of alchemists in the early modern Netherlands.

This is the image of Thomas Wijck that emerges in Elizabeth Drago’s excellent new book, which is the first study to address this important aspect of Wijck’s work and career (notably, there is no catalogue raisonné on the artist). As a number of more recent studies, Drago’s book moves between the monographic and thematic, offering new perspectives on Wijck as a painter, printmaker, and draughtsman, as well as the wider artistic, cultural, and professional contexts to which he belonged. Departing from the long-held view that Wijck was predominantly a painter of Italianate scenes and member of the Bamboccianti in Rome, Drago positions him within his native Haarlem as a leader and innovator of the pictorial genre of alchemy. Wijck treated the subject of alchemists at least forty times during his career – a substantial part of his oeuvre of around 120 paintings – and it was integral to his success and reputation both during and after his lifetime. While Drago demonstrates how Wijck’s alchemical imagery participated in a culture invested in art, science, and the natural world, she also seeks to place the artist in “a greater Netherlandish continuum of illusionistic rhetoric and practice,” showing how his paintings form part of “the long dialogue between artistry and experiment” (23).

Painted Alchemists loosely follows Wijck’s career over the course of six chapters, in addition to an introduction and epilogue. The first chapter investigates the polemical attitudes towards early modern alchemy, what Drago earlier describes as “a set of speculative tools by which individuals manipulated their environments” (16). From there, she establishes the pictorial traditions from which Wijck’s scenes would later emerge. She establishes the dichotomy between the negative image of the alchemist popularized by the engraving after Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s Alchemist from c. 1558, and Johannes Stradanus’s ‘positive’ print of Distillatio from the Nova Reperta (c. 1590). Unlike Bruegel’s misguided and greedy alchemist, who seeks to transform base metals into gold through transmutation – a subject that Wijck never depicted – Stradanus’s busy workshop highlights the usefulness and benefits of this “newly discovered” alchemical process. As Drago explains, Stradanus’s print offered an alternative pictorial tradition for a later generation of artists, including Wijck’s near contemporary, the Flemish painter David Teniers the Younger. Although the discussion of Teniers, who produced a large number of alchemical scenes in the second half of the seventeenth century, is an important one, the leap that Drago makes from Stradanus to the mid-seventeenth century can feel rather abrupt at times. One wonders to what extent Wijck was aware of the example of his Flemish contemporary.

The reader finally meets Wijck in chapter two, as Drago more fully introduces the artist and the emergence of genre painting in Haarlem in the early decades of the seventeenth century. The striving for innovation in Haarlem’s artistic milieu and Wijck’s interest in ‘modern’ subject matter – a concept Drago associates with Gerard de Lairesse’s Het Groot Schilderboek of 1707 – laid the groundwork for Wijck’s development of his “pictorial brand” (24 and 63). Central to this discussion is the local urban context of Haarlem and Wijck’s increasingly visible role in the community. He became a member of the Guild of St. Luke in 1643, and subsequently held the roles of warden and dean in the 1650s through the 1670s. It comes as a surprise at the end of this chapter, however, that Drago addresses why Wijck and alchemy have been largely overlooked by scholars (91). This discussion is certainly welcome, but it would have been better suited within the introduction in order to highlight the strengths of Drago’s book and her contribution to a growing body of scholarship addressing “the connections between alchemy and art-making” (95).

The heart of Painted Alchemists is the discussion of Wijck’s work in chapter three, which is supported by thirty-two color illustrations located in the middle of the book, as well as black and white images throughout the text. Drago organizes the paintings into three distinct categories: the alchemist as family man, artisan, and scholar. Inhabiting “hybrid domestic-experimental spaces,” Wijck’s alchemists, often portrayed with their families, also function as hybrid figures. They show their manual and intellectual labor, domestic virtue, and engagement with society at large, reflecting “the productive craftsman” as well as the “creative and intellectual experimenter” (146–47). This chapter also presents a chronology of Wijck’s alchemical scenes for the first time. Drago refutes the long-held claim that Wijck produced his paintings of alchemists during the latter part of his career, following a journey to London in the early 1660s. Instead, she convincingly argues that Wijck’s interest in alchemy began as a young artist in Haarlem in the mid-1640s and continued steadily throughout his life.

Chapters four and five address the local aspects of Wijck’s art in Haarlem and his experiences abroad in Italy and England. Building on ideas raised in chapter two, Drago investigates the industries in Haarlem that relied on alchemical processes, such as bleaching and brewing, and the ways in which they impacted Wijck’s approaches to the subject matter. This inherently ‘local’ aspect of alchemy and its representation find a parallel in the rhetorical tradition associated with artists like Jan van Eyck and, more directly, Hendrick Goltzius. These artists’ own experimental techniques – from Van Eyck’s so-called invention of oil painting to Goltizus’s experimentations with alchemy – provided Wijck with an important source of inspiration and precedent.

In chapter five, Drago expands this framework to Wijck’s journey to Rome and Naples (1644–53) and later London (1663 and 1672–74), which introduced the artist to new sets of ideas of alchemical inquiry. In Rome, for instance, Wijck produced one of his most unusual paintings, The Alchemist and Death, which, as a “thematic outlier,” is his only painting to deal with ideas of mysticism and the occult. Yet Drago rightly argues that the painting should be understood as “that most alchemical of things: an experiment” (192). Wijck’s explorations of innovative themes continued in London, a period in which he worked in the orbit of John Maitland, advisor to Charles II. The royal circle’s interests in alchemy must have further inspired Wijck, who introduced the depiction of alchemists in “foreign” dress into his paintings. These representations are as much an indication of alchemy’s Eastern origins as Wijck’s effort to showcase his own worldliness.

Drago’s final chapter unites Wijck’s imagery of alchemy with his role as a painter of such scenes. She shows how the very making of art is the product of the alchemical process, as well as an affirmation of the artist’s ultimate mastery over nature. The close parallels between art and alchemy are evident in Wijck’s material and technical knowledge, including his frequent use of vermillion and effort to depict the play of light and reflection across different surfaces and textures: the laboratory’s basins, alembics, powders, books, and papers become an indication of Wijck’s artistic virtuosity. These scenes also take their place among the painted studios of Rembrandt van Rijn, Gerrit Dou, and Wijck’s teacher, Adriaen van Ostade, but they occupy a “liminal category” not unlike alchemy itself (256). Wijck’s alchemists, as Drago demonstrates, are craftsmen, proto-scientists, and intellectuals, part of a world in flux that was subject to many of the same challenges facing artists. Drago brings these contradictions to the forefront in her fascinating book, reshaping how we understand and appreciate Wijck as an artist, and his place within the broader landscape of experiment and creativity in the early modern world.

Lara Yeager-Crasselt

The Leiden Collection