Halfway through a painting career spanning nearly forty years Caesar van Everdingen (1616/17 – 1678; active 1636 – 1673) created an unusual portrait historié depicting Diogenes Looking for an Honest Man (The Hague, Mauritshuis; cat. no. 14). A rough-clad Diogenes holds aloft the lantern which he was reported to have thrust in the faces of his contemporaries as he queried their honesty. Van Everdingen, however, has transported the Greek Cynic from the third century BC to a Dutch town square in 1652 where he mingles among the clearly portrayed members of a multi-generational Dutch family. It is with this novel portrait that Van Everdingen makes his cameo appearances in my own classrooms. When I have the time, van Everdingen’s elaborate paintings for the Huis ten Bosch are shown to demonstrate the classizing taste of the court of the Stadhouder’s widow, Amalia von Solms, in The Hague. And then he exits my stage.

Nearly three hundred years ago, however, while commenting on another portrait, Arnold Houbraken wrote in 1718 that van Everdingen’s Old Civic Guard “was enough to bring him enduring fame.” In his lifetime Caesar van Everdingen was a highly successful artist. Working with Jacob van Campen, he painted the organ shutters for the St. Lawrence’s Church in Alkmaar, which must have led to the commission for two large wall paintings and ceiling panels of the Oranjezaal in the Huis ten Bosch. Other important projects included paintings for the town hall of Alkmaar, for the Rijnland district water board, and three large group portraits for the “Old” and “New” civic guards of Alkmaar. He died a wealthy man.

Van Everdingen’s fluidly painted classicizing paintings, however, have been cast in the shadow of “Dutch naturalism” in the intervening centuries. Many have gone under the names of other artists. His eclipse is well illustrated by the number of paintings attributed to him in the sales catalogues of the Getty Provenance Index. While 1012 paintings are listed as by his younger brother, the landscape painter Allart van Everdingen, only twenty-nine are attributed to Caesar; of these, at least twelve are landscapes clearly by Allart. An entry in the catalogue of a London sale of 1803 notes that his “works are extremely scarce,” although it incorrectly gives the reason that he “died at a very early period.” (Caesar van Everdingen died at the age of 61 or 62 after a nearly forty-year career). Of the paintings exhibited here, at least nine at one time or another were attributed to other artists including Govert Flinck (cat. 3), Bartholoeus van der Helst (cat. 15), Karel Dujardin (cats. 22a and b), Gerard de Lairesse (cats. 26a and b), Ferdinand Bol (cat. 30), a “French artist around 1800 (cat. 12), and unknown, possibly Paulus Bor (cat. 19). Part of the problem was the similarity of his work with that of some of his contemporaries including Salomon and Jan de Braij in Haarlem, and the wide range of styles in which his portraits appear to have been created. Another issue may be the lack of a signature on many of his works: nineteen, or less than half of those exhibited here, bear his monogram. Moreover, successful enough not to have had to work for the open market, his death inventory and that of his widow list more than seventy paintings – most by van Everdingen himself – which indicates that he kept a substanial number of his easel paintings, including nine in the exhibition.

Van Everdingen and other artists working in the classicizing style that for several centuries have inappropriately been designated as “not Dutch” have slowly made their way back into the canon of Netherlandish painters. Van Everdingen was represented by fourteen paintings in the groundbreaking Dutch Classicism exhibition of 1999-2000 on view in Rotterdam and Frankfurt. Celebrating the 400th anniversary of his birth, the monographic exhibition devoted to the artist at the Stedelijk Museum, Alkmaar – the catalogue of which is here reviewed – displayed 41 works, two-thirds of the 62 works given to the artist in Paul Huys Janssen’s monograph and catalologue raisonné of 2002. Supported by a prestigious Dutch Turing Award II, the exhibition provided a well-balanced view across the artist’s entire career of portraits, history paintings, tronies, two still-lifes of stone busts, a design for a stained-glass window, and – remarkably – a painted model ship, all illustrated in color. A good addition to the literature on the artist, the exhibition and catalogue included a recently discovered and attributed work (cat. 12), and two paintings that in 2002 were deemed lost (cats. 26a and b).

The beautifully designed catalogue reproduces 150 color illustrations accompanied by a text that is both scholarly and accessible to a wider public. The entries, whose authors include a number of scholars who had participated in the 1999-2000 exhibition including Albert Blankert and Jeroen Giltaij, as well as Paul Huys Janssen provide fresh assessments of subject identifications, iconographic associations, and portrait sitters’ identities. Preceding these entries are a series of essays in a novel format: four sections devoted to the artist’s life by Christi M. Klinkert (1), his classicism by Jeroen Giltaij (2), his portraits by Rudi Ekkart (3) and his celebrated idealizing, fluid brushwork by Caroline van der Elst (4). Additional four-page “spotlights” focus on specialized aspects or works: his brother Allart van Everdingen by Christi M. Klinkert; van Everdingen and the Oranjezaal by Lidwien Speleers; a foray into the relatively new area of costume study in an essay on “Caps, Hats and Bows in Caesar van Everdingen’s Work” by Sabine Craft-Giepman; and concluding with two welcome considerations of technical examination by Caroline van der Elst of the two 1657 civic guard paintings, restored for the exhibition. The first outlines the perspective systems of the paintings in consideration of the room in the Waag in which they were painted, and before one of them was cut down. The second presents the discovery of “probably the first ever restoration that can be attributed to a Dutch painter of the Golden Age,” a patch cut from a parchment document dating from the 1570s that was inserted before the painting was completed.

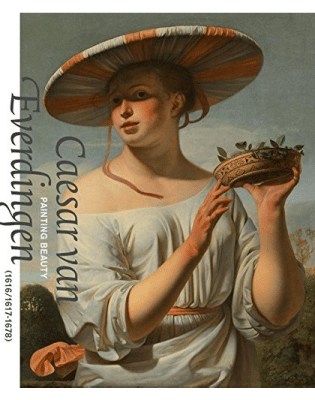

As Giltaij states, the style and subjects of van Everdingen’s history paintings may be related to those being created elsewhere in the Northern Netherlands. Many of van Everdingen’s semi-genre paintings of females in half-length wearing transparent garments provocatively sliding off their shoulders revealing one or both breasts may be associated with the tradition of courtesans favored by the Utrecht Caravaggisti (cat. 2 and figs. 8, 18, 92). Several of these are highly unusual, however, including a recently discovered and attributed young woman leaning over a parapet, wearing a swept-back black hat and a black cloak whose sobriety dramatically contrasts with the prounounced cleavage that it reveals (cat. 12). Another female half-length, in two versions, depicts an unusually dressed young woman warming her hands under her cloak, held over a brazier, identified as an allegory of winter (cats. 13a and b).

Rudi Ekkart points out that van Everdingen produced portraits “that display so many disparate characteristics that it is virtually impossible to distill a coherent picture of Van Everdingen as a portrait painter from them.” These range from the family portrait historié described above to civic guard portraits (cats. 6, 23, 24) and three-quarter length portraits of middle-aged couples dressed in black garments surmounted by stiff linen mill-stone collars (cat. 1). Still to be accounted for is the range of styles and qualities of these works, including the disparity between the extraordinary high quality of the painting thought to be a self-portrait (cat. 32), and the rather awkward placement of the head on the flattish torso of the portrait of Maria van Steenhuijsen (cat. 9). These would benefit from additonal investigation into the circumstances of commission, the patron’s desires, and possible other participating hands.

The field of Netherlandish art history is undergoing a profound, revitalizing transformation, attending to new artists and the locations in which they worked, their subject matter, styles and even media. The modest number of sixty-two works given to van Everdingen by Paul Huys Janssen in 2002, created in a career spanning nearly forty years, suggest that more paintings by this superb artist are yet to be identified. Nonetheless, the Alkmaar exhibition and its accompanying catalogue are a welcome addition.

Ann Jensen Adams

University of California at Santa Barbara