This book is based on the PhD thesis submitted to Princeton University by Abigail Newman, a recently appointed deputy curator at the Rubenshuis in Antwerp. The author starts her survey with the accurate remark that the Spanish words “Flandes” and “flamenco” are to be understood in an elastic way, connecting them with the art production in the Burgundian Netherlands. These terms are thus to be considered a “pars pro toto” for the entire Seventeen Provinces. From the outset, painting made in “Flandes” seems to have had a very specific meaning for Spanish collectors and art lovers. Indeed, already from the days of Jan van Eyck it was admired for its outspoken realistic illusionism.

In an introductory chapter the author deals with the economic and cultural connections that from medieval times onward had existed between the Low Countries and the Iberian world. Rightly she underlines the importance of the growing specialization in Netherlandish painting. Thus, in early modern times the outspoken realistic character of Northern portrait, still-life and landscape painting seems to have exerted an undeniable fascination on art loving Spain. In the next chapters of her book Newman further explains how this “Flemish” influence in Spanish painting was realized by migrated Netherlanders as well as by the massive influx of Flemish paintings, thanks to a continuous interest by local collectors and patrons as well as by the growing activity of Antwerp art dealers on the Iberian peninsula.

Among the many Netherlandish painters active in seventeenth-century Madrid, it was above all portrait painters that seem to have played an important role. In this context Newman rightly remarks that the artistic output of these artists especially met the Spanish preference for Northern realism, as becomes clear from the refined illusion of tactility in the rendering of costume details in the portraits of princes and dignitaries. In this reviewer’s opinion, Flemish artists knew well how to meet this particular Spanish taste for the illusionistic rendering of the details of sumptuous clothing and precious jewellery. Thus it is striking how Gaspar de Crayer, who never set a foot on Spanish soil, in his portraits of Spanish princes and high ranking aristocratic dignitaries, such as King Philip IV, the Duke of Olivares or the Marquis of Léganès, paid the highest attention to the suggestion of tactility when painting his sitters’ shining cuirasses, velvet curtains or plumed hats.

Abigail Newman further shows how the Spanish taste for “Flemish realism” may also be found in a marked preference for the kitchen scenes by Pieter Aertsen or Joachim Beuckelaer, which in turn strongly influenced the Spanish “bodegones,” as seen in the earliest works by Velázquez. This extended to flower pieces, such as the flower wreaths by Jan Brueghel the Elder and Daniel Seghers, painted around a religious subject by another artist. In the same way, game pieces by Frans Snyders were of importance for local artists as Juan van der Hamen y Léon and others. The seventeenth century witnessed a hitherto unseen bulk trade of Flemish paintings destined for Spanish clients in which the Antwerp firms ruled by the Musson and Forchondt families were especially active.

Finally, a coda is especially devoted to Rubens and his unique importance for Spanish art. Newman convincingly explains that above all Rubens was regarded in Spain as the great history painter who worked in the tradition of the Italian masters of the High Renaissance. Spanish admiration for his personality and artistic output was of quite another order than the attraction exerted by the illusionism and sense of tactility in the more usual “flamenco” painting.

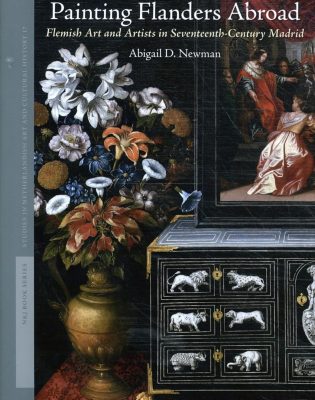

The book, a recent volume in the Studies in Netherlandish Art and Cultural History series, a supplement series to the authoritative Netherlands Yearbook for History of Art, is well laid out with intelligently chosen color illustrations.

Hans Vlieghe

Centrum Rubenianum, Antwerp