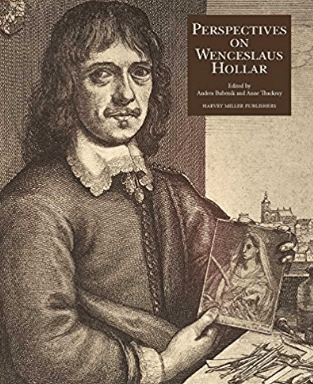

Only the most renowned printmakers ever seem to get closer analysis. But Wenceslaus Hollar, the multinational etcher (1607 Prague-1677 London), has chiefly received exhibition attention only, so this series of essays, largely organized by his diverse themes by equally international contributors, offers welcome depth. Bubenik has already ventured into this period through her study of Dürer-Rezeption in the seventeenth century (2013), while Thackray curated a Hollar exhibition (2010) at the University of Toronto. Thus these two editors have complementary backgrounds in relation to their chosen printmaker, and the publishers have provided them with clear and ample illustrations. As their introduction makes clear, they aim to situate Hollar in the wider fields of science and knowledge as well as art. All scholars who use this volume will want to consult the New Hollstein volumes (9), edited by Giulia Bartum (2009-12).

Alena Volrábová, curator of prints and drawings in Prague, examines the artist’s early career (27-39) and concludes that he was instructed in the complexities of etching by Jacob Hoefnagel rather than either Aegidius Sadeler or Joris Hoefnagel, as asserted previously. His early travels through Germany established a network of colleagues, including Matthäus Merian the Elder, before he met Thomas Howard, Earl of Arundel, in Cologne. That fateful encounter in 1636 led to the close association during the 1630s and 1640s of patron and printmaker, whose 59 images “ex collectione Arundeliana” are examined – and usefully catalogued – by Robert Harding (41-77), an antiquarian book dealer in London. Their association also spanned Civil War years in Antwerp exile (1644-1651/52). Harding also introduces other English noble patrons of prints and recalls the role of Lucas Vorsterman as another of their printmakers. But the systematic reproduction of master drawings for Arundel in England featured both Leonardo and Holbein works, and in Antwerp Hollar reproduced artworks from other collections. His prints after Dürer are then (re-)examined by Bubenik (79-89), who adds to the challenges to the reductive term of “reproductive printmaker” and asserts the virtuosity of the works (which could be compared to engravings by the Wierixes or Cornelis Cort in the previous century) as well as the homage to chosen prototypes.

A neglected corner of Hollar imagery emerges from Thackray’s study of his Praemonstratensian prints (91-116), especially around 1650/52, and of the founding figure, St. Norbert, after Abraham van Diepenbeeck (also favored by Van Dyck within Counter Reformation iconography in Antwerp). Of course, an artist need not subscribe to a religion to make images for it, as Lucas Cranach’s imagery for Cardinal Albrecht of Brandenburg attests; however, Hollar seems to have converted to Catholicism at some point, and he continued that dangerous affiliation back in London after 1651, even if he left Prague in 1627 as a Protestant under enforced re-Catholicization.

Several essays follow with discussions about topographical prints by Hollar. David Flintham, a specialist in military history, links Hollar to tactical sites (117-36), “castles, fortifications, and sieges,” including a series of late prints of Tangier (1669), discussed separately by Simon Turner (173-92) in terms of artistic accompaniment to a scouting expedition for King Charles II. Flintham views these images for their accuracy, especially of military engineering in an era when warfare as well as defenses against advanced artillery produced rapid advances. Not discussed here is the great before-and-after topographical riverside view of London recording pre-Fire and post-Fire profiles, so the artist was capable of using drawings much later for his prints, though always based on close observation originally. Simon Turner (137-71), a Hollar specialist, who worked with Giulia Bartrum on the New Hollstein, picks up the London thread but much more for documentation in drawings and prints of major individual landmark sites, especially palaces and Westminster Abbey.

If his isolated landmarks often have the character of specimens, Hollar also produced scientific prints. Here they receive only limited attention, but Nathan Flis (193-218), a curator at the Yale Center for British Art, discusses his association with English natural history painter Francis Barlow (c. 1626-1704), his own specialty. The two artists might have shared modelbooks, and Hollar etched several bird designs by Barlow, published in 1658.

This book principally attends to Hollar as an accurate illustrator, depicting items based on close observation, whether of surviving old master drawings and prints, or else of settings in London and abroad as well as avian fauna. For the most part, he is viewed in isolation relative to other printmakers and their projects, but his social connections emerge collectively from this sequence of essays. If this is not the first place to get an overview of Hollar – the exhibitions perform that function well already – it is, at last, a place to delve more deeply into at least some aspects of his artistry through favored subjects.

Larry Silver

University of Pennsylvania