Readers of HNA Reviews are more than familiar with the odd term, “Northern Renaissance,” and its problematic link between Northern Europe and the classical revival that properly centered on Italy’s ancient heritage. Moreover, for German art, that term principally and most effectively focuses on Albrecht Dürer and his trips to Italy, thus, his hometown of Nuremberg has dominated historiography of early modern art history. Yet beyond Nuremberg, Germany’s “second city,”Augsburg, truly did claim to have its own classical heritage, including a foundation by Augustus himself, named Augusta Vindelicorum. And, as Rachel Carlisle’s deeply researched new book claims, the term “Augsburg Renaissance” holds a many-faceted, but complex instance of self-fashioning for that major urban economic powerhouse of the early sixteenth century.

Recently, Augsburg has finally been discovered by current museumgoers. A major exhibition (Vienna – Frankfurt, 2023) proclaimed the city as a Renaissance in the North, centering on its principal artists, Hans Holbein the Elder as painter and Hans Burgkmair as printmaker.[1] Carlisle, too, emphasizes transalpine exchange, visual as well as commercial, into Augsburg along trade routes, particularly connected to Venice But, as her title implies, her focus is on “the age of print,” both antiqua lettering as well as Burgkmair’s enthusiastic adoption of classical architectural and figural forms. Central to her account as a leitmotif running through multiple chapters is Dr. Konrad Peutinger: antiquarian and amateur archaeologist, art patron, adviser to Emperor Maximilian I, as well as city secretary of Augsburg. Carlisle states her claim forthrightly in her Introduction: “the visual evidence overwhelmingly indicates that in early sixteenth-century Augsburg, artists and patrons actively sought to produce antique-related works of art and architecture and often looked to Italy for their models.” (p. 31)

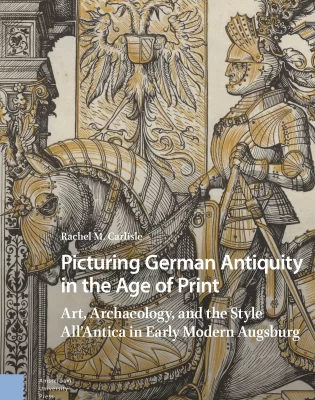

Peutinger and his collection form the subject of the first chapter, “Local Antiquities and the Romanae vetustatis fragmenta.” That title refers to his sylloge, or collection, of local ancient fragments of inscriptions, the first to be printed north of the Alps. Its publication also was a technical marvel. Published by Augsburg native Erhard Ratdolt, it used gold metallic ink in several luxury editions, thus combining the latest printing novelties with antiquarianism, including majuscule font. Print not only recorded recovered knowledge from Peutinger’s personal antiquities collection, but it also disseminated that knowledge, based on direct observation, through the early modern technology of book publishing. Carlisle connects Ratdolt’s printing techniques to earlier German print imagery, while emphasizing the volume’s learned humanist content and limitation to an elite audience. A similar limited edition, woodcut on vellum with an added gold printing block, appears in the Burgkmair print, Emperor Maximilian I on Horseback (Chicago, Art Institute; fig. 9).

In Chapter Two, “Ancient Coins, Printed Portraits, and the Idea of Authenticity,” Carlisle returns to Peutinger’s use of direct observation of ancient sources for his project of a Kaiserbuch, including portrait depictions by Burgkmair of Roman and Holy Roman emperors. This early collaboration between Peutinger and Burgkmair was never published, but the surviving profile heads, based on ancient coins as models, employed similar historical research. Here Carlisle adduces related genealogical images and notes the development of another contemporary innovation north of the Alps: the profile portrait medal, pioneered by Hans Schwarz of Augsburg in 1518. Schwarz commemorates both local cultural figures, including Peutinger, as well as other leaders from the Augsburg Diet of that year. Like Ratdolt’s reproduction of ancient texts, Burgkmair’s reproduction of ancient likenesses in the permanent profile pose suggests true “counterfeit” (contrafactum) or “from life” (ad vivum) authenticity of ancient figures akin to Schwarz’s own portraits of contemporaries.[2]

Turning from these careful investigations of close documentation and use of evidence, Carlisle’s Chapter Three, “Transalpine Exchange, the Welsch, and the Deutsch,” examines contrasting contemporary concepts of style, whether Italy-derived – redefined by her as all’ antica – or else indigenous and “Germanic.” She reprises Ratdolt’s pioneering color printing technique, adopted by Burgkmair for chiaroscuro woodcuts with especially Italianate forms of figures and architecture.[3] In Chapter Six, Carlisle returns to Augsburg’s local adoption of “Architecture All’antica,” particularly in the super wealthy Fugger family’s funeral Chapel and its multi-media decoration. In the organ shutters by painter Jörg Breu and the sculpted putti by Hans Daucher,[4] the Fuggers demonstrated their commercial contacts with Venice while also emulating the prestige of Italian court culture and reasserting Augsburg’s Roman heritage through their choice of Welsch style. Carlisle, however, also asserts that here many strands converge: “In the Fugger Chapel of St. Anna, the foreign and local, ancient and modern, inextricably mingle.” (240) Following Andrew Morrall, her Chapter Four, “Archaeology of the Printed Page,” traces Breu’s use of Italian print sources as well as Burgkmair’s prior contributions in the field of all’ antica ornament.[5]Particular attention focuses on Breu’s marginal designs for the so-called Prayerbook of Emperor Maximilian I and on Peutinger’s influence on how Breu contributed allegorical imagery and dialogues with marginal motifs by other German artists to the project (148-65).

Following Christopher Wood’s analysis of the Germanic flavor of forest wilderness landscapes, Chapter Five, “Locating Antiquity in the German Landscape,” ranges widely outside Augsburg to trace the influence of Tacitus’s rediscovered Germania on such artists as Dürer and Albrecht Altdorfer.[6] This chapter mixes a number of subjects beyond landscape and digresses from its main focus on Augsburg. But it does capture some principal Deutsch subjects, such as wild men, satyrs, and hermit saints, to which Carlisle briefly adds peasant subjects, even though a number of these figures adopt (and disguise) classical figure types.

Suddenly, however, the imperial program of woodcuts for Maximilian I intrudes (186-96), followed by consideration of equestrian portraits of the emperor (196-203), which returns to Burgkmair’s 1508 woodcut (see above). This imagery, which adopts Renaissance forms going back to classical sculptural prototypes, reinforces the ruler’s dual association of knightly virtue with imperial stature. The city’s close association with Emperor Maximilian I, already the subject of a rich local exhibition,[7] deserved fuller and separate treatment in Carlisle’s book and would once more have tightly bound the Augsburg’s connections, through Peutinger, with local artists at work on programs of imperial iconography. This abbreviated discussion remains one tantalizing shortcoming of her otherwise well formulated case study of urban visual culture.

In many ways, Carlisle’s book provides a fitting application of the turn to historical roots, outlined and theorized in Christopher Wood’s landmark Forgery, Replica, Fiction, a book which, significantly, also employs the term “German Renaissance.”[8] By historicizing her analysis in Renaissance Augsburg, she firmly grounds that larger phenomenon and defines its uniquely local meaning. Although Augsburg was riven by the religious and political upheavals of the Reformation after the 1520s,[9] and also suffered from the deaths of Emperor Maximilian I and most of the artists and artisans covered in this book, Carlisle anchors their imagery from the walls the recent Vienna-Frankfurt exhibition within its historical urban context. In support, Amsterdam University Press within its series, Visual and Material Culture, 1300-1700, has produced an attractive, well-illustrated volume to provide the foundations for Carlisle’s cogent analyses.

Larry Silver

University of Pennsylvania, emeritus

[1] Guido Messling and Jochen Sander, eds., Renaissance in the North: Holbein, Burkgmair, and the Age of the Fuggers (Munich: Hirmer, 2023).

[2] Ashley West, “Hans Burgkmair and Conrad Peutinger: Reevaluating the Artist-Humanist Relationship,” in Wolfgang Augustyn and Manuel Tegel-Welz, eds., Hans Burgkmair. Neue Forschungen (Passau: Klinger, 2018), 45-67; Larry Silver, “The Face is Familiar: German Renaissance Portrait Multiples in Prints and Medals,” Word & Image 19 (2012), 6-21; Jeffrey Chipps Smith, “A Creative Moment: Thoughts on the Genesis of the German Portrait, Medal,” in Stephen K. Scher, ed., Perspectives on the Renaissance Medal (New York: Garland, 2000), 177-200; Peter Parshall, “Image Contrafacta: Images and Facts in the Northern Renaissance,” Art History 16 (1993), 554-79.

[3] Elizabeth Savage, “Hans Burgkmair’s Colour Woodcuts: An Overview,” in Augustyn and Teget-Welz, Burgkmair Neue Forschungen, 333-66

[4] Messling and Sander, Renaissance in the North, 276-77, nos. 3.08-09; 281-84, nos. 3.14-16. Carlisle interprets the recently discovered putto with a garland with a German rosary context (230-40), visually preserved in a drawing of the Fugger Chapel by Master S.L. (fig. 95).

[5] Andrew Morrall, Jörg Breu the Elder: Art, Culture and Belief in Reformation Augsburg (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2001).

[6] Christopher Wood, Albrecht Altdorfer and the Origins of Landscape (Chicago: University of Chicago, 2014); also Larry Silver, “Forest Primeval: Albrecht Altdorfer and the German Wild-erness Landscape,” Simiolus 13 (1983), 4-43.

[7] Heidrun Lange-Krach, ed., Maximilian I. 1459-1519: Kaiser, Ritter, Bürger zu Augsburg (Regensburg: Schnell und Steiner, 2019).

[8] Christopher Wood, Forgery, Replica, Fiction: Temporalities of German Renaissance Art (Chicago: University of Chicago, 2008).

[9] B. Ann Tlusty and Mark Häberlein, eds., A Companion to Late Medieval and Early Modern Augsburg (Leiden: Brill, 2020).