Every historian of Dutch art knows of Rachel Ruysch (1664-1750) but few know much about her. Flower painter, daughter of the famed anatomist Frederik Ruysch… and there it usually stops. There has not been a monograph on her in almost seventy years, and the dissertation on her early work has never been published.1 Even scholarly articles have been few and far between. Her works feature in the catalogues of the important museums in which they hang and, occasionally, in exhibitions on still life or on women artists. This scholarly neglect stands in stark contrast with the esteem she enjoyed in her own lifetime, when her works were collected and admired by the urban and courtly elites of Europe, and her praises penned by poets.

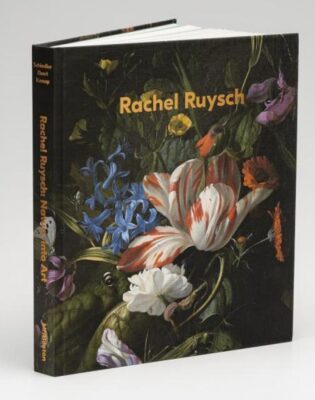

The present book takes a significant step toward repairing that neglect. It serves as the exhibition catalogue for a show of Ruysch’s work held in Munich, Toledo, and Boston in 2024-2025. However, its scope and arrangement are those of an independent book, one that will stand long after the exhibition has closed. It consists of ten essays of varying lengths, within which most of the works shown at the various venues are illustrated and discussed or at least mentioned; this includes about half of the over 150 works by Ruysch that survive. The essays include contributions by a biologist, a literary historian, a historian of biodiversity, and several paintings conservators as well as the show’s curators and other art historians. The variety of writers is appropriate for a study of Rachel Ruysch for, as we gradually learn from reading this book, she was at the center of scientific life in late-seventeenth and early-eighteenth century Amsterdam, and was appreciated and collected in part because of her aesthetic response to the new globalism of botany and biology. This truly set her apart from her mostly male predecessors and contemporaries.

The essays begin with an introduction to Ruysch by Robert Schindler. Ruysch, we learn, was not only talented, she was consistently favored by fortune: she came from a family of artists and scientists, was encouraged by her father and married an artist who supported her career, had eleven children and kept painting, lived to be almost 85 years old, and literally won the lottery – 75,000 guilders, a huge sum in 1723. Schindler takes us back to her earliest work and considers who, besides her teacher Willem van Aelst, might have inspired her. He also devotes a section of his essay to Rachel’s sister Anna, a very capable artist as well. Usually she is dismissed as a fairly amateur imitator of her sister, but Schindler illustrates numerous works by her hand and suggests that she might have collaborated on some of Rachel’s larger and more demanding works. He introduces the Ruyschs’ scientific milieu and suggests ways Rachel’s practice might have related to it, a topic continued throughout the other catalogue essays. He also, of course, outlines the growth of her fame and her fortunes, from admission into the painters’ confrerie in The Hague to being appointed court artist by Johann Wilhelm II, Elector Palatine in Düsseldorf.

This overview is followed by an essay from Marianne Berardi that zooms us in for a close look at several of Ruysch’s individual paintings. In fact she covers each type of composition painted by Ruysch – the forest floor, the nosegay, the bouquet in a vase – but for each one she also takes a single example and subjects it to a very fine visual analysis, parsing out the details of how Ruysch achieved various effects and even moods, how she handled color and space and illumination with “deceptive artlessness” that was really ever so carefully planned. Even the insects are neatly placed so as to guide the viewer’s eye among the vegetation. Berardi makes telling comparisons to works by other flower painters, emphasizing that Ruysch’s paintings create a tremendous first impression, but also repay careful attention to every detail in their complex natural worlds.

Next, Anna Knaap provides a long essay setting Ruysch’s production into the scientific and particularly horticultural networks of her day, emphasizing the roles that women played in these networks, and the steady introduction of new plants from the Dutch colonies during Ruysch’s lifetime. Both of these factors were crucial to Ruysch’s production and prominence. Ruysch must have known the famous gardener Agnes Block, who lived only a few streets away from her in Amsterdam and who was a patron of female artists for the cataloging of her botanical collection. Ruysch’s own father was a professor at the Amsterdam Hortus Botanicus, and important figures in the world of horticulture, like Pieter de la Court in Leiden, commissioned paintings from her. The sheer number of species now available to the avid student of plants was remarkable: the Leiden Hortus had 1100 species in 1600, 3000 in 1685, and 7000 in 1740.2 So, Ruysch’s depiction of non-native species comes as no surprise but is in fact different from the work of her colleagues. Knaap takes some time over Still Life with Cactus in a Blue Vase, one of a number of works that include exclusively imported plants: one arrangement includes a pineapple; another, an eggplant. By arranging these new and strange plants into familiar compositions, Ruysch helped to absorb them into the world of European science and horticulture.

The last long curatorial essay, by Bernd Ebert, comes a bit later in the book and is a carefully researched description of how Rachel Ruysch’s paintings were collected in her lifetime and during the rest of the eighteenth century. It is difficult to pinpoint who was buying her early work, and the first part of the essay is often based on well-informed speculation. Once she became connected to Johann Wilhelm, though, the documentation becomes much more solid and it is very interesting. The elector’s fondness for her paintings (he kept several of them in his bedchamber) continued through his descendants and also sparked the interest of other aristocratic collectors in Vienna, Schleissheim, Salzdahlum and other courts although Ebert questions whether all of the Ruysches listed in their inventories were really by her. Finally, Ebert goes over paintings that can be traced to non-aristocratic collections in The Netherlands and in Germany.

Other essays in the book are somewhat shorter. Bert van de Roemer considers what united art and medicine, or how their goals might be similar, according to the theories of Ruysch’s time. He compares the immortality of sorts granted to medical and also botanical specimens by Frederik Ruysch’s preservation techniques with the eternal blooms of Rachel’s paintings. Biologist Charles Davis has inventoried the species in sixteen Ruysch paintings from over the course of her life, finding the highest plant diversity in paintings from the middle of her career. A single painting from late in that period contains no fewer than thirty-six species. Animal and insect life is considered by Katharina Schmidt-Loske, who has studied 89 paintings and identified native and non-native insect species in them: the longhorn beetle was a particular favorite. Ruysch did not try to recreate the actual natural habitats of her creatures and indeed, as Schmidt-Loske argues, shows the native and the exotic side by side. Robert Schindler’s second essay in the catalogue identifies a drawing of a Surinam Toad as being by Ruysch, by whom (extraordinarily) no other drawings are known. The short essay “Forever in Bloom” by Josephina de Fouw, Nouchka de Keyser, and Jorinde Koenen peeks behind the curtain in the portrait of a nineteenth-century collector to discover that it was painted over a work by Ruysch that he owned. And finally, Lieke van Deinsen provides a fascinating essay on the ut pictura poesis trope and how it plays out in a dozen poems written in honor of Ruysch and published, possibly with a nudge by her son Frederik, during her lifetime. Many of the poems, including the first three in the volume, were penned by up-and-coming women writers in Dutch literary circles. Two poems from the volume are included, in translation, later in the present book, along with an appendix listing the botanical species inventoried in her works.

Altogether, this is a magnificent publication, covering many new aspects of Rachel Ruysch’s artistry and assuring that they will no longer fade into the background of her career. Her unique commitment to science and the diversity of plant life, her ingenuity as a designer, and her connections with women artists and writers, are added to the long-appreciated beauty of her paintings. This catalogue will stand as a key text on Ruysch for a long time, but should also spark further interest in this remarkable woman.

Elizabeth Honig

University of Maryland

[1] Maurice H. Grant, Rachel Ruysch, 1664-1750 (Leigh-on-Sea: F. Lewis, 1956); Marianne Berardi, Science into Art: Rachel Ruysch’s Development as a Still-Life Painter (Ph.D. diss., University of Pittsburgh, 1998).

[2] Anna C. Knaap, “Amsterdam’s Flora” in the present book, p. 80.