In her methodologically capacious new book, Claudia Swan attempts to show how materials from around the globe amassed in the early modern Netherlands illuminate the formation and development of the Dutch state. Throughout her study, Swan puts herself in conversation with others writing about colonialism, mercantilism, and the presence of foreign commodities in Dutch visual culture. The result is a work that invites and stimulates intellectual engagement rather than insists upon a single point of analysis. In its embrace of diverse materials as well as diverse theoretical positions, Swan’s Rarities of these Lands not only makes important claims about the founding of the Dutch Republic but also speaks to the interdependence of commerce, art, and political self-fashioning among populations across the early modern world.

Rarities of these Lands aligns with several recent publications and exhibitions of art that also study the circulation of objects from and texts about Asia within the Dutch Republic, notably Asia in Amsterdam: The Culture of Luxury in the Golden Age (2016), The Global Lives of Things: The Material Culture of Connections in the Early Modern World (2016), Inventing Exoticism: Geography, Globalism, and Europe’s Early Modern World (2015), Netherlandish Art in its Global Context (2016), Rembrandt’s Orient: West Meets East in Dutch Art of the 17th Century (2021), and Still Life and Trade in the Dutch Golden Age (2007). Swan is a generous scholar, quick to draw attention to the contributions of other authors, but she is also clear about the ways that her approach differs from theirs. By limiting her investigation to the period before the 1648 Peace of Westphalia, Swan focuses our attention on the formation of the Dutch Republic and the role Asian goods play in that moment of political self-definition. Her project is framed by this question: What did the emerging state want others to understand as “Dutch,” in their acquisition, gifting, and trade in exotica? Swan is not the only author to tackle the question of “Dutchness” in its relationship to foreign goods or to attempt to understand how the Republic’s engagement with Asian materials is distinct from that of other countries in Europe, but she is one of the most successful. In part this is because Rarities of these Lands limits and defines its terms. Swan employs “exotic,” for example, conservatively, taking it to mean simply “foreign” and avoiding proleptic associations of “otherness.” Instead, rarities (rariteijten), a word employed in many of the seventeenth-century texts discussed in her book, is the term around which Swan’s analysis centers. She argues that whether gifted, collected, studied, or used for daily life, rarities must be understood as commodities. Pushing this correlation further, as commodities, rarities are fungible goods, exchangeable and replaceable in ways that art is often thought not to be (more like Edam cheese than a Rembrandt painting). The commodification of rarities, Swan argues, allows “these lands” from which the rarities come to stand for both their foreign place of origin (often sites in Asia) as well as their European place of reception and exchange (the Dutch Republic). Rarities thus become a manifestation of the emerging Republic’s pivotal position on the global stage.

Rather than tracing the practicalities of the trade that brought goods from Asia to the Netherlands, Rarities of these Lands focuses on the conceptual nature of commodities, specifically on rarities as metaphors for political presences. In the book’s first three chapters, for example, Swan introduces Amsterdam as a “world emporium.” She explains how a conjunction of new architecture (the Town Hall, Amsterdam Exchange, and India House), printed imagery (including broadsheets and book illustrations), and ephemeral pageants (such as Marie de’ Medici’s 1638 visit to Amsterdam) crafted an image of the city as “the navel of the world,” naturalizing the abundance of foreign wares among the Dutch as evidence of the power of their newly emerging state. The mechanisms that brought this cornucopia to the Netherlands – including piracy, looting, naval warfare, intricate diplomatic negotiations, and repellant acts of inhumanity – were camouflaged, Swan argues, by a triumphal rhetoric carried out in visual culture.

In following chapters, the book shifts focus slightly to consider Dutch self-representation beyond the boundaries of Europe and looks closely at the inventory of a 1612 gift from the Dutch state to the Ottoman court. Here too, Swan is clear that her aim is not to chart reciprocal or responsive relationships between the Dutch and the other countries with whom they were in contact. She focuses instead on one side of the diplomatic endeavor to investigate the Dutch deployment of rarities as part of a developing political practice. Swan argues that the Dutch carefully chose the objects given to the Ottoman court, intending not simply to flatter the Sultan and promote commerce between the two states, but to present him with rarities that (even if, or especially because, they were foreign wares) would also be understood as “Dutch” commercial goods. The inclusion of Birds of Paradise among the gifted items is an especially challenging case study as these commodities are neither manufactured (like porcelain) nor cultivated (like pepper) and their inclusion, and Swan’s discussion of them – particularly their legless and wingless representation in many Dutch texts – demonstrates the innovativeness of her approach. Swan notes that evidence suggests the Ottoman reception of these gifts may not have been what the Dutch intended. Within the aims of this book, however, the effectiveness of the gift is less important than the motivations behind it.

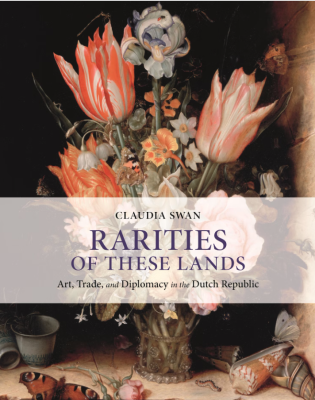

Rarities of these Lands is a richly illustrated and capacious work. It discusses canonical oil paintings as well as less well-known prints, drawings, porcelain vessels, stuffed birds, dolls’ houses, and objects in many other media. Rich in formal analysis, the passages describing individual works of art are beautifully articulated. That said, Swan’s book is not primarily a study of isolated objects but rather an examination of categories of things – things that, in many cases, are nonextant. The author explains that compilation and translation are central to the Dutch state’s efforts to align foreign commodities with the Republic’s emergent identity. Immersed in a rich trove of archival resources, Swan’s own method in this work is also one of compilation and translation, as texts become the vehicles through which we grasp the meanings of commodities that no longer exist. Although the effects of commercial exchange between Asia and the Dutch Republic will continue to be a topic of scholarly debate for decades to come, Rarities of these Lands is an essential work for understanding one moment of its history.

Dawn Odell

Lewis & Clark College