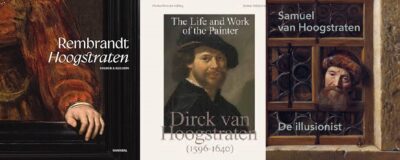

These three publications, one monograph and two exhibition catalogues, complement one another, celebrating three artists of very distinct characters, abilities, ambitions and generations: Dirck van Hoogstraten (Dordrecht, 1596-1640), Rembrandt (Leiden, 1606-1669 Amsterdam), and Samuel van Hoogstraten (Dordrecht, 1627-78). Rembrandt’s youthful meteoric rise to prominence and his Amsterdam activities are familiar, and the successes and fame of his pupil Samuel van Hoogstraten are well established. Dirck van Hoogstraten is understandably obscured by the success of his son, Samuel. Dirck belongs to a milieu of artisans and Samuel to the foremost intellectuals and artists of his time in Europe. Both demonstrate the impact of Rembrandt in their own art.

Michiel Roscam Abbing, an independent scholar who has long researched Samuel van Hoogstraten with particular attention to archival documents, and Robert Schillemans, retired curator of the Museum Ons’ Lieve Heer op Solder, state in their introduction that they “attempt to reconstruct Dirck’s life” and describe his work. This they have done in full, writing the definitive study with insights into his extended family, artistic milieu, religious affiliations and tensions, and economic circumstances. They have established a paper trail that permits Dirck’s life and activities to emerge as much as possible. Dirck’s authentic oeuvre consists of nine paintings, three drawings, and nine prints. Additionally, 28 works are mentioned in inventories and auction catalogues. His references to Jacopo Bassano, Rubens, Rembrandt, Lastman and other artists indicate his awareness of current trends in the larger art world. When Dirck died suddenly at the age of 44, he left his widow with seven young children to be raised by guardians among the Mennonite community of Dordrecht. The three sons Samuel, Jan, and François would mutually support each other in their later careers as artists and a publisher.

Astutely, the authors assess the disparate talents of the conventional Dirck and his more ambitious and accomplished son Samuel. However, the extended family ties help account for Samuel’s extraordinary success. His great-grandfather, Franchoys, worked for the mint in Dordrecht, as did Dirck’s father-in-law and possible teacher, Isaac de Coninck; such a familial connection with metalsmithy and official civic posts certainly supported Samuel’s position artistically, socially and politically, as the mint positions were hereditary and he himself became Provost in 1659 and Mint Master in 1673.

The Vienna and Amsterdam catalogues are reviewed here as publications, rather than exhibitions. Their “common thread” is the convincing illusion sought by Rembrandt and Samuel van Hoogstraten, who had similar approaches to portraiture in seeking framing devices and dynamic poses. However, where Rembrandt sought to represent the elusive consequences of speech and attitude, Van Hoogstraten depicted what he observed. Both catalogues interweave Van Hoogstraten’s treatise Inleyding tot de hooge schoole der schilderkonst… (Rotterdam, 1678) throughout their essays. They share some authors and topics but diverge to reflect the characters of their respective host museums and cities. Vienna highlighted Samuel van Hoogstraten’s relationship to the city and to his second teacher Rembrandt, with attention to collecting their works. A parallel timeline juxtaposes Rembrandt’s paintings with Van Hoogstraten’s, giving a visual graph of their major pieces in each decade. By pairing Van Hoogstraten with Rembrandt, Vienna broadened the scope and audience for the exhibition. Amsterdam focused on Van Hoogstraten alone, emphasizing his mastery of optical illusion, printmaking, and independence from Rembrandt. The Vienna catalogue consists of substantial essays by 11 authors, while the Amsterdam catalogue featured 19 relatively short essays by 14 authors; both covered similar aspects of Van Hoogstraten’s art and achievements, with some overlap. The Amsterdam catalogue has versions of several Vienna essays; these include Sabine Pénot’s discussion of Van Hoogstraten and Emperor Ferdinand III in Vienna, Leonore van Sloten’s discussion of illusionism, and David de Witt’s analysis of the connections and distinctions between Rembrandt’s nae ‘t leven or art after life and Van Hoogstraten’s Zichtbare Werelt, or visible world. Topics discussed only in the Vienna catalogue include fashion accessories by Marieke de Winkel and the science of astronomy and optics by Paolo Sanvito. In the Amsterdam catalogue Thijs Weststeijn emphasizes Van Hoogstraten’s global interests and Stephanie Dickey highlights his prints. Erma Hermens, along with additional authors, examines the grounds of 17 paintings in the Amsterdam catalogue and, in the Vienna catalogue, the materials and techniques of two works for Ferdinand III, the Courtyard of the Vienna Hofburg and the Old Man at a Window (1652 and 1653; Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna). These complementary essays demonstrate how ground tones function within the color range of his paintings, and how the text of the Inleyding relates to his technique.

Samuel van Hoogstraten’s life is chronicled in his treatise in anecdotes and by his pupil, Arnold van Houbraken, and supplemented by additional documentation. By the age of thirteen, he learned the basics of art from his father, whose early death cut short this training. He then attended the Dordrecht Latin school. Concurrently, he became familiar with optical experiments and the camera obscura through Johan van Beverwijck, for whose books of 1642 and 1644 he made 13 etchings. He studied with Rembrandt from about 1642 to 1647. Though based in Dordrecht, Van Hoogstraten was in Vienna 1651-1654, where he worked for the Emperor Ferdinand III and court officials. In 1652, he traveled through Italy to Rome. And in 1656, he married, a requirement for the position in the Mint. From 1662 to1667 he lived in England, and in 1668, resettled in The Hague.

During the 1640s, Van Hoogstraten closely followed Rembrandt’s style in single figure paintings and finished history drawings. He then turned to elegant portraiture and genre scenes, occasional mythologies, religious histories, perspectives, and trompe-l’oeil still lifes. One of these, possibly the Letter Rack with Rosary and Playing Cards (1651; Prague Castle), was among the three paintings he brought to Vienna in 1651 to show Emperor Ferdinand III, who was amazed by it and presented the artist with a gold chain and medallion. Van Hoogstraten was sensitive to what would best delight and surprise his patrons, who were particularly astonished by his deceptively lifelike images of objects, interiors, and architecture. He was preceded in painting the letter rack by Vittore Carpaccio (Hunting on the Lagoon, recto, Letter Rack, verso, c. 1490-1495, Los Angeles, J. Paul Getty Museum) and immediately followed by Edwaert Collyer and Cornelis Norbertus Gijsbrechts, among others. In his letter rack paintings, Van Hoogstraten repeated some items and varied others, appealing to certain patrons with some objects as well as providing autobiographical references with his own writings and possessions.

When Van Hoogstraten returned to Dordrecht from his travels south in 1656, he began to paint doorkijkjes, interiors with views through doorways, following the lead of Gerard ter Borch and others, as in The Slippers (c. 1655-1662, Musée du Louvre, Paris). Spurred by Carel Fabritius’s distortions of a street in the View of Delft (1652, The National Gallery, London), he created the Perspective Box to show how a manipulated scene appeared to be corrected when viewed though a peephole (c. 1658, The National Gallery, London). In England he further developed visual games of illusion in several large perspectives that are intended to open a view through a wall and startle the viewer as he comes upon them (1662, Dyrham Park, Gloucestershire; c. 1662-1667, Dordrechts Museum, Dordrecht).

Long noted but only recently examined extensively, Samuel van Hoogstraten’s 1678 treatise has been reprinted (1969), digitized (Warburg Institute), and translated with annotations in French (Jan Blanc, 2008) and in English (Celeste Brusati and Jaap Jacobs, 2021). His writings and his art have been analyzed by these and other authors (notably H.-J. Czech 2002 and Thijs Weststeijn, 2008 and 2013). Since these publications are well known, they are cited here only by author and year. Two symposia have been devoted to him (2009 and 2025; this most recent one, from April 2025, is on line from the RKD-Netherlands Institute for Art History: (https://vanhoogstraten.rkdstudies.nl/contents/). A complete on-line survey of his oeuvre is planned by the RKD. The complexities of his treatise and the variety of his paintings are daunting to researchers, and the happy proliferation of publications in the past few decades elucidates both his writing and his art, and their interdependence. This is further demonstrated in the Amsterdam and Vienna catalogues.

Dirck van Hoogstraten modelled himself after Rembrandt in his Self-Portrait, sporting a gold-trimmed beret and knowing smile (c. 1634-1640, Private Collection, United States). So did Samuel in portraying himself wearing fanciful clothing (1644, Museum Bredius, The Hague; 1645, The Princely Collections, Vaduz-Vienna, Liechtenstein). In his last Self-Portrait, Samuel recalled the pose of Rembrandt’s 1640 Self-Portrait (The National Gallery, London), but presented himself as an erudite gentleman and author with allegorical attributes including Atlas holding up the world (1677, Huis Van Gijn, Dordrecht; frontispiece etching for the Inleyding). Like Rembrandt, Samuel was competitive with his teacher and peers, and keenly ambitious. Unlike the occasionally thorny and proud Rembrandt, Samuel aimed to please, and cultivated a personal style that successfully furthered his courtly and civic aspirations.

Amy Golahny

Lycoming College, emerita

Addendum

October 11, 2025

Given the small number of paintings known by Dirck, it is noteworthy that another has recently turned up. On September 25, 2025, Hampel Fine Art Auctions, Munich, auctioned a painting by Dirck van Hoogstraten, titled “Biblical Scene in a Palace.” The canvas is large, 79 x 97 cm. and monogrammed. The subject is Daniel interpreting the dream of Nebuchadnezzor, which concerns a statue of gold, silver, bronze and clay that is destroyed, and allegorizes the four monarchy system of divine rule (Daniel 2). According to Michiel Roscam Abbing and Robert Schillemans the painting must date from Dirck’s Pre-Rembrandtist period (oral communication October 2025). It is now in the Collection Pieter van Loon, Dordrecht.

Amy Golahny