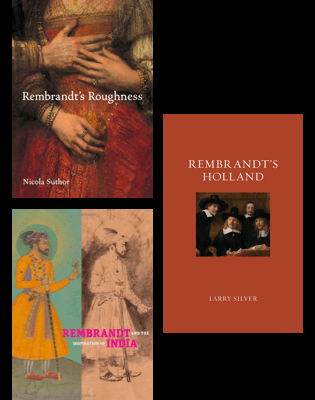

Nicola Suthor, Rembrandt’s Roughness. Princeton – Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2018. 240 pp, 82 color illus, 79 b&w illus. ISBN 978-0-691-17244-6.

Stephanie Schrader, ed., with contributions by Catherine Glynn, Yael Rice, and William W. Robinson, Rembrandt and the Inspiration of India. [Cat. exh. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, March 13 – June 24, 2018.] Los Angeles: The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2018. 160 pp, fully illus. in color. ISBN 978-1-6060-6552-5.

Larry Silver, Rembrandt’s Holland. London: Reaktion Books, 2018. 213 pp, color illus. ISBN 978-1-7802-3847-0.

Nicola Suthor’s Rembrandt’s Roughness, a revised and expanded English translation of the author’s Rembrandts Rauheit (Munich: Wilhelm Fink, 2014), is the most ambitious and challenging of the three books under review. In this important though sometimes opaque study, Suthor breaks with familiar contextual, iconographic, technical, and stylistic approaches to confront directly Rembrandt’s radically unconventional artworks. The sensory impact and power of his art, she asserts, cannot be fully illuminated by established explanatory frameworks. Suthor frames her investigation in a phenomenological perspective, and focuses on what she defines somewhat loosely as “the rough structure of the medium” in Rembrandt’s paintings and prints, primarily of his late period and including some of his most celebrated works. Suthor identifies visual phenomena such as the play of shadows, exposed imprimatura, heavy impasto, expressive brushwork, and rich color as passages of representational ambiguity, pictorial anomalies that go beyond a mimetic function and, in her view, deepen the iconographic meaning of the depicted subjects. By looking closely at and painstakingly describing these features, she seeks to revitalize description as a methodological tool of art history.

Suthor’s goal is to involve the reader/beholder in an understanding of visual art as emerging from an interactive process of perception, and through which, she claims, we gain access to Rembrandt’s representational “intensions.” As far as I understand, in phenomenology intention signifies the idea that consciousness is directed toward something in the world, and in the case of art, as Edmund Husserl argued, refers to a conscious idea realized as an image object. An artwork is thus a form of communication between artist and viewer with discrete material properties that mediate both the maker’s and beholder’s perception or experience. Suthor aims further to “refashion subjective experience into intersubjectively valid assertions and reinforce description as epistemic practice” (8), grounding her claims in contemporary or near contemporary sources that comment (usually negatively) on Rembrandt’s expressive originality, including texts by Sandrart (1675), Van Hoogstraten (1678), and Houbraken (1718). Rightly emphasizing that Rembrandt’s complex approach to pictorial representation poses a challenge to the positivist conceptual framework of conventional art historical methodology, she offers a new perspective that defines art as a phenomenon that lies at the intersection between objective and subjective perception.

Suthor’s analyses of artworks can be insightful. I found compelling her discussion of Rembrandt’s powerful, late-state transformations of The Three Crosses as palimpsests that dramatize the fundamental infigurablity of God’s wrath, as well as her argument that Rembrandt’s expressive, textured brushstrokes in the shift protecting the woman’s body in Woman Bathing of 1654 convey subliminally the violence of the prototypical scenes of Bathsheba, Susannah, or Callisto, narratives to which the painting relates but cannot be reduced. She also intriguingly interprets Rembrandt’s self-portrayal as Zeuxis dying of laughter in relation to the moment of severance between artist and work, and as an abandonment of the act of painting, by linking it to topoi about the superiority of incomplete works left by artists at their death. The rough facture of Rembrandt’s brushwork in this and other late self-portraits, she argues, exemplifies a “signing off” or an ending consistent with Rembrandt’s conviction, according to Houbraken, that a painting is finished when the artist has achieved his intention.

Other interpretations are less persuasive, however. I am not convinced by Suthor’s identification of a “blurred spot” (53) on Christ’s robe in The Hundred Guilder Print as a shadow cast by his raised left hand, which she reads as reaching down to “touch” the more legible shadows of the hands of two women imploring his blessing. Some of her interpretations also assign greater narrative weight to motifs than they seem capable of bearing. Does the shadow cast by Banning Cocq’s hand on Van Ruytenburch in The Nightwatch operate independently of its representational function to indicate the captain and lieutenant’s mutually dependent relationship? Suthor is more compelling when she describes how Rembrandt’s thick, highly differentiated application of rich red paint in Isaac and Rebecca (The Jewish Bride) and Prodigal Son evokes and heightens the aura of intimacy between the figures, who do not look at each other. As she argues, Rembrandt’s lavish use of color subtly transmits emotional content by inviting the viewer’s sensorial response, which in turn sensitizes us to the depicted theme of intimacy. But the reflections of yellow from Isaac’s sleeve on Rebecca’s red dress and of the father’s red cloak on the prodigal son’s head seem to me to function as ambient colors that contribute to the works’ atmospheric effects rather than as carriers of semantic value.

Suthor’s effort to define more precisely and investigate the originality and power of Rembrandt’s art by probing its material and expressive characteristics is timely and welcome. Her writing can be difficult to follow, though, perhaps due in part to being translated from German. She also sometimes abruptly interrupts the analysis of an artwork to consider briefly another work that only tangentially relates to her main argument. For a study that prioritizes close looking and careful description of visual and material nuances of artworks, moreover, it is surprising that she sometimes misidentifies panel paintings as canvases (Woman Bathing and Artist in His Studio). Most importantly, Suthor’s interpretations of passages of tension between artifice and representational illusionism in Rembrandt’s artworks are largely hypothetical, as she readily admits. “[I]n the end,” she writes, “it is up to the viewer to recognize … a deliberate motif and to believe in the meaningfulness of its existence.” (56) A leap of faith is therefore required in order for her claims to carry conviction. Ultimately this provocative book is a unicum rather than a model for rethinking or reinvigorating Rembrandt studies. While fresh and sometimes illuminating, her method seems idiosyncratic and inimitable.

In contrast to Suthor’s rejection of historical framing, the authors of Rembrandt and the Inspiration of India, catalogue of an exhibition at the J. Paul Getty Museum, embrace contextual and global perspectives to explore a remarkable group of Rembrandt drawings after Mughal Indian paintings. Rather than a conventional catalogue with detailed entries for each of the 20 drawings included in the exhibition (almost all of the 23 surviving Rembrandt copies of Mughal art), the book is comprised of four essays by the Getty curator Stephanie Schrader and contributing authors Catherine Glynn, Yael Rice, and William W. Robinson. The collaboration between scholars of Dutch art (Schrader and Robinson) and Mughal painting (Glynn and Rice) offers a welcome balance between Western and non-Western viewpoints that yields interesting new insights into Rembrandt’s engagement with the increasingly interconnected world of early modernity.

Schrader’s introductory essay situates the drawings within Amsterdam’s global trading and artistic economies. She addresses Dutch trade arrangements with Mughal rulers and access to knowledge about India, Rembrandt’s patrons with VOC ties, and Dutch collectors of Mughal art of the later seventeenth century, notably Nicolaes Witsen who owned 465 Indian paintings, some of which may have belonged to his father Cornelis, from whom Rembrandt borrowed a large sum of money in 1653. As Schrader emphasizes, Rembrandt also collected foreign art and artifacts as works of artificialia (works of human artifice) and naturalia (specimens on nature) in his kunstkammer, the contents of which are known from the inventory of his possessions drawn up in connection with his declaration of bankruptcy in 1656. The inventory lists a book of “curieuse minijateur teeckeninge nevens verscheijde hout en kopere printen van alderhande dragt” (curious drawings in miniature as well as woodcuts and copper engravings of various costumes). Sometimes taken as evidence that Rembrandt owned the Mughal paintings he copied, the description, as Schrader observes, is too vague to support that contention. Prints by Dutch and other Netherlandish artists also made their way to India in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, inspiring a number of Mughal imitations that, like Rembrandt’s drawings after Mughal art, accommodate alien models to native aesthetic conventions.

Rembrandt executed all the drawings on luxuriously expensive Japanese paper, enhancing the sheets’ aura of exotic luxury. As Schrader notes, the group comprises more than half of his drawn copies, and demonstrates Rembrandt’s unusual willingness to surrender his own artistic vocabulary in order to imitate a foreign representational mode. Rembrandt captured the refined, angular, miniature-like style of his Mughal models with a characteristically loose, seemingly spontaneous touch and heightened expressivity, sometimes adding passages of wash to evoke the originals’ colored backgrounds, and even touches of red and yellow in faces, hands, and details of clothing. So accurate are Rembrandt’s drawings after the originals that almost all of them can be identified as portraits of Mughal emperors and princes of the imperial court, including eight of Shah Jahan, Rembrandt’s contemporary. Despite their precision, Rembrandt did not use the drawings as the basis for his renderings of clothing and accessories in prints and paintings. But he did base the etching Abraham and the Angels of 1656 on his drawing after a Mughal painting depicting Four Mullahs, which in the eighteenth century was incorporated into wall decoration of the Millionenzimmer at Schönbrunn Palace, Vienna. Schrader emphasizes the print’s generic Near Eastern headdresses and other departures from the Mughal prototype. Yet given the close correspondence between the compositions, even down to the motifs of a jug and flat dish, the original work’s importance for Rembrandt should not be underestimated. As has often been noted, the Mughal painting, which shows four men kneeling on the ground, probably offered him a model for depicting figures seated in a fashion considered by Europeans to be a continuation of biblical practices.

What purpose, then, did Rembrandt’s drawings after Mughal paintings serve? Schrader proposes that Rembrandt may have produced the series to appeal to a wealthy collector. William Robinson offers an alternative explanation, first advanced by Marijn Schapelhouman, that strikes me as closer to the mark: Rembrandt made the unusually meticulous copies on rare and costly Asian paper “as substitutes of unavailable originals” (55), and for his own encyclopedic collection featuring artistic, natural, and artifactual marvels of the world. Robinson surmises that the drawings probably remained in Rembrandt’s possession until he was obliged to part with them at one of the forced sales of his paper art that took place between 1656 and 1658. A single buyer likely purchased them as a group, Robinson suggests, as seems to have been the case with other drawings organized according to theme. His proposal is strengthened by the fact that all but two of the 23 extant drawings after Mughal originals bear the collector’s mark of the English painter and theorist Jonathan Richardson the Elder, and are first recorded in the 1747 sale catalogue of his estate, in a lot described as “A book of Indian Drawings, by Rembrandt, 25 in number.” Robinson carefully traces the sheets’ subsequent ownership history and entry into scholarly discourse, convincingly refuting recently expressed doubts about authenticity. With exacting and eloquent phrasing, he describes the nuances of penmanship, brushwork, technical inventiveness, mimetic precision, and expressivity that are hallmarks of Rembrandt’s versatile draftsmanship.

Glynn’s and especially Rice’s essay offer instructive counterpoints by focusing on the Mughal paintings and their agency in facilitating cross-cultural exchange. As Glynn shows, Rembrandt’s models were among the earliest Mughal paintings to arrive in Europe, dating from just a few decades earlier than his copies, and were produced in the imperial workshop under the patronage of Shah Jahangir and his son Shah Jahan. She contrasts the highly regularized production system of the Mughal court workshop with the vibrant and diversified Dutch art market in which Rembrandt worked, underscoring the Mughal works’ exceptionally rarified original viewing conditions and limited circuits of exchange. It is difficult to identify Rembrandt’s exact sources because many versions of favored compositions were the norm in Mughal practice. But based on closely observed differences between Rembrandt’s drawing Akhbar and Jahanghir in Apotheosis (Rotterdam, Museum Boijmans-van Beuningen) and two extant Mughal versions of the scene attributed to the famous Bichitr and an unknown artist, Glynn demonstrates that he must have seen an unknown version, also quoted by Willem Schellinks in two fantastical paintings dating from the same period. Glynn also confirms the identification of the Four Mullahs Seated under a Tree at Schönbrunn Palace as Rembrandt’s model for the print Abraham Entertaining the Angels of 1656, since the Mughal original, dated 1627-28, is an early prototype for later iterations of the composition.

Rice interestingly challenges the priority accorded to Rembrandt in this episode of cross-cultural contact, casting him instead as a participant in the continuing process of exchange that defines Mughal art’s global character and circulation. As Rice emphasizes, European prints flowed into South Asia well before Rembrandt’s time, and sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Mughal court artists frequently adapted European models, including Dutch prints, in acts of cultural appropriation and artistic rivalry. The hybrid, European-style paintings they produced were assembled into albums together with contemporary Persian paintings and paintings after Persian models, drawings, calligraphies, and impressions of European prints. The royal albums showcase the cosmopolitanism of the Mughal court and the shahs’ specifically Islamic vision of universalist rule. Rice points out that the albums’ heterogeneity is distinctive relative to earlier sixteenth-century North Indian manuscripts, and that the prominence of paintings after Persian works associated with the contemporary Safavid court and those after European engravings signifies the Mughal rulers’ claims to hegemonic, global authority. Many of these highly prized albums also migrated early on as gifts to other courts and their contents were often dispersed and/or reconfigured by subsequent owners, indicating that diffusion and fragmentation were integral to their function. For Rice, Rembrandt’s engagement with these cosmopolitan and portable Mughal paintings, whether in an intact album or as loose leaves, fulfilled their “global aspirations” (74).

Larry Silver makes no claim to breaking new ground in Rembrandt’s Holland, part of Reaktion’s Renaissance Lives series. Instead, he offers an accessible, concise, up-to-date and well-written introductory study that firmly situates Rembrandt’s life and work within Dutch history and society. Noting that “Rembrandt and the Netherlands grew up together,” Silver weaves together a biographical sketch, sensitive analyses of artworks, and a comprehensive overview of Dutch politics, society, religion, and artistic culture. He covers extraordinary ground in a brief book, laying out for the general reader the trajectory of Rembrandt’s art and career in relation to the main contours of Dutch history, especially politics. In four chapters, Silver maps the diverse religious affiliation of Rembrandt’s sitters onto the Republic’s religious pluralism, recounts Rembrandt’s initial cultivation of patronage of the Stadholder’s court and Amsterdam’s patricians, places him within the expanding cultural horizons brought by Dutch dominance of global trade, and correlates Rembrandt’s later difficulties in sustaining patronage from powerful groups with the ongoing political tensions between the House of Orange and Amsterdam’s regents. He avoids historical determinism by highlighting Rembrandt’s extraordinary creativity and ambition, his rivalry with artistic heroes, and defiance of institutional and social norms. Yet Silver’s determination to track Rembrandt’s career and art with the development of Dutch history leads him to include a number of hypothetical political readings of paintings, such as Ganymede, The Nightwatch and Claudius Civilis, which he admits are subject to debate because Rembrandt’s own political affiliations or sympathies are unknown. Perhaps it would have been more effective to emphasize Rembrandt’s singular position as a creative figure who was both shaped by Dutch history and contributed to the Republic’s horizons of expectation.

Michael Zell

Boston University