The wide-ranging material discussed in Zell’s welcome study relates to the values ascribed to art objects. Quantitative monetary currency provides one measure, and others are qualitative: diplomatic power, personal gifts, artistic exchange, and offerings in domestic and foreign business transactions. These measures are examined fully with erudite authority and elegant prose. Although the focus is on Dutch seventeenth-century art, this densely informative volume includes Italian, French, Spanish, English and Flemish gift-giving.

The first chapter surveys how art was used as gifts to monarchs for diplomatic purposes. Charles I of England and Philip IV of Spain are among the most famous monarchs as collectors; their preferences for Italian Renaissance paintings were well known and often recognized in gifts. Purposes of gifts were various, relating to political capital, treaties, marriage matches, and religious persuasion. When courting the Infanta Anna Maria in 1623, Charles I (then Prince of Wales) visited Madrid and picked up some remarkable Italian paintings from Philip IV. Quite unabashedly interested in influencing the English monarch to become Catholic, Francesco Barberini, Cardinal-Protector of England, gave Henrietta Maria a number of Italian paintings, knowing she would show them to Charles I; the king, however, remained staunchly Protestant. Portraits were both customary and personal for they represented the power of position as well as presumed friendship.

The second chapter concerns gifting in the Dutch Republic. With its mercantile and seafaring economy, the Dutch had both wealthy and middle-class art collectors, whose family and business connections were often closely connected. The exchanges and gifts could also be of a non-material kind, as in the case of the schoolmaster David Beck, who recorded in his 1624 diary about 1000 transactions in that year; many of these concerned hospitality, drinks, meals, lodging and poems, and they belonged to the pattern of Beck’s daily life (see further Irma Thoen, Strategic Affection?: Gift Exchange in Seventeenth-Century Holland, Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2007). For Dutch burgomasters and officials, accepting material gifts created obligations, and the fine line between a bribe and a favor was recognized in Amsterdam and The Hague. Internationally, the Dutch East India Company was able to operate in Asia by bestowing appropriate gifts to the rulers of India, Japan, Persia, and Turkey, for without such customary offerings, the company could not negotiate.

During his years in Brazil (1637-1644), Johan Maurits commissioned the Dutch artists accompanying him to document visually the land and its peoples, and also acquired a quantity of artifacts. When he made spectacular gifts from Brazil to the Elector of Brandenburg (1652), Frederick III of Denmark (1654) and Louis XIV (1679), he did so to strengthen ties following the shift in power from the House of Orange-Nassau to the Amsterdam Regents, after the death of Willem II (1650). His motivations were mutual service, honor, and cultural and social capital. The case of Johan Maurits indicates the richness of the material presented here, as it has produced a number of monographs (see most recently Michiel Roscam Abbing, Brazilië zien zonder de oceaan over te steken, Amsterdam: Lias Uitgeverij, 2021).

The third chapter concerns Rembrandt, who used his art both to further his social aspirations and to express his gratitude to friends; he portrayed Jeremias de Decker in appreciation for writing about him, for example. Rembrandt was often reluctant to fulfill or even accept lucrative commissions. He identified with Zeuxis, whose paintings were beyond monetary value, and he considered his own work and worth to be above patrons’ wishes and payment. Thus, he placed the inestimable and intangible valore di stima on his work. I add that Don Antonio Ruffo complained about the Alexander and Homer in 1662 but nonetheless begged Rembrandt in vain to send sketches for further paintings; Rembrandt’s disdain for the Sicilian collector led to his stalling with modelli in 1666 for another Italian nobleman, Francesco Maria Sauli, who would have commissioned from Rembrandt two grand altarpieces for the Carignano family church in Genoa.

Chapter Four treats drawing as a leisure activity of the cultured elite. Sketching the countryside was a pastime for amateur as well as professional artists; their drawings were made for private enjoyment rather than commercial distribution. Drawings with inscriptions by Jan de Bisschop and Constantijn Huygens Jr. indicate that these friends enjoyed sketching excursions together, and exchanged their sheets as tokens of affection and esteem. Drawing belonged to the education of boys; the Dutch were recognized for their skill, as it was useful to record military information, inventions and travels. In this regard, I mention that the ideal – and evidently actual – Latin school curriculum included calligraphy and drawing, according to the 1625 schoolordre.

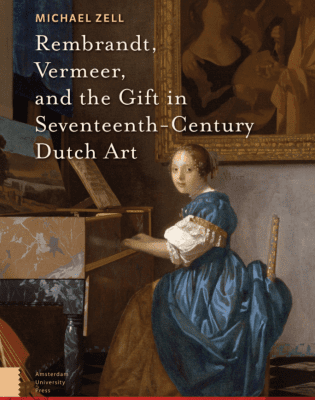

The final chapter discusses Vermeer’s imagery in Petrarchan terms of decorous female beauty and courtship as love poems, gifts in themselves. Zell explores Vermeer’s paintings by referring to Adriaen van de Venne and other authors, to make larger points about the artist loving his own work and seducing the beholder with it, about the paintings within Vermeer’s paintings, and about Vermeer’s use of tone and light rather than mimetic detail. The nuanced analysis of Vermeer’s distribution of his paintings proposes that the painter’s production was non-commercial and favored honor over profit. The privilege of owning a Vermeer was a gift in itself, and the artist and posthumously his wife carefully ensured that the few lucky and recorded owners recognized that privilege.

Zell’s analysis of gifting may be extended far beyond the Dutch Republic. In the present, diplomatic presents raise questions of ownership and corruption, and common practice includes gifting one’s own creative production. Such gifting is paralleled by authors. Association copies of published books are those inscribed that reveal personal connections between giver and recipient. American authors of the nineteenth century were particularly keen on presentation copies inscribed in detail, a practice that permits tracking their exchange networks (see, for example, Leon Jackson, The Business of Letters. Authorial Economics in Antebellum America, Stanford University Press, 2008). One wishes that artists were more conscientious about inscribing their works, and ratiocination and reasoning are required to determine gift circumstances, which Zell has demonstrated exceptionally well.

Beautifully produced with 205 color illustrations, this publication is also designed for each chapter to be independent of the others, as each chapter has its own bibliography. Although this adds 50 pages to the printed volume, it makes for efficient electronic posting and wide readership.

Amy Golahny

Logan A. Richmond Professor Emerita of Art History, Lycoming College