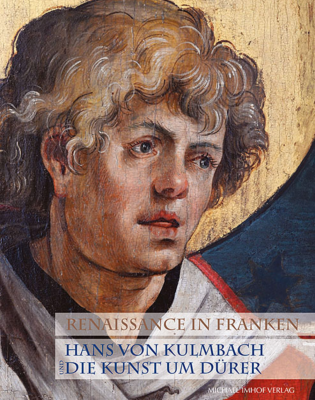

Visitors to the St Sebald’s church in Nuremberg are often struck by the colorful painted triptych epitaph for patrician Lorenz Tucher, which features a central scene of the Madonna and Child in a Renaissance throne niche, surrounded by charming cherubs and complemented by flanking saints, Catherine and Barbara, before an expansive summer landscape (ills., pp. 36, 78-79). If that picture looks like the work of Albrecht Dürer himself, the answer is that it was painted by one of his gifted associates during the teens of the sixteenth century and based on a Dürer drawing (W. 508; Berlin). Dated 1513 and signed with his initials H.K., this is the core work of Hans von Kulmbach, one of the finest of the Meister um Albrecht Dürer, as the 1961 Nuremberg exhibition proclaimed this group, whose contours and individual identities still remain hazy and understudied (the basis is a Winkler 1959 monograph). Kulmbach has been somewhat more fortunate than his associates, especially at the hands of Barbara Butts, who wrote a 1985 Harvard dissertation on his drawings, later published in Master Drawings (Vol. 44 2006, pp. 127-212). Now Kulmbach’s entire career, including his designs for stained glass and relation to sculpture, appears in an edited volume of essays, accompanying an exhibition in Kronach.

The essays begin with an overview by Frank Matthias Kammel of Kulmbach’s Nuremberg as a “brainpool” and pioneering location of early modern culture. Many of the objects discussed are still in situ or in the Germanisches Nationalmuseum. They include the 1492 Erdapfel, or world globe, of Martin Behaim and the civic self-portrait of Nuremberg by Michael Wolgemut in the massively illustrated 1493 World Chronicle by Hartmann Schedel, as well as self-portraits of leading sculptors in the city: Adam Kraft in sandstone; Peter Vischer the Elder in bronze; plus Veit Stoss’s mark and signature on his St Sebald’s epitaph relief for Paul Volckamer. Thus Dürer and then Kulmbach were following in a new era of artistic self-confidence and individual assertion in their shared city.

Co-editor Teget-Welz, a recent contributor to a Wolgemut exhibition (Mehr als Dürers Lehrer, Nuremberg, 2019), devotes close attention to Kulmbach’s career, including his export connections to Cracow and his commissions for altarpieces and portraits before his death in 1522. His Nuremberg window was short, documented from around 1508 until his citizenship in 1511. In that latter year he produced for King Sigismund of Poland the beautiful retable with a central Adoration of the Magi (Berlin, Gemäldegalerie), in which, besides Dürer, Jacopo de’ Barbari facial types show influence. Cracow was also linked to another Nuremberg artist, Veit Stoss, who lived there for fifteen years, and Kulmbach’s St Catherine Altarpiece (1515) is still in situ at St Mary’s with the great Stoss retable. But the close Dürer connection in painting recurs in Kulmbach’s 1514 epitaph with donors, Coronation of the Virgin (Vienna), closely modeled on the Heller Altarpiece. In effect, when Dürer withdrew from larger religious paintings, Kulmbach filled that void. He also supplemented Dürer designs for Emperor Maximilian’s Triumph with a monogrammed drawing of horsemen bearing laurels (by 1517; Berlin). Teget-Welz also gathers Kulmbach portraits, the best known of which is Munich’s 1511 Kasimir von Brandenburg, and he includes mention of drawings and designs for stained glass, which will be discussed in later essays.

Evaluating the contributions of Kulmbach’s as painter, Matthias Weniger notes many missing works from Poland. He emphasizes the naturalism of the saints’ faces (though family resemblance of the types seems stronger than their variety) as well as the portraits. He stresses the innovative spatial breadth of St. Sebald’s triptych landscape expanse and related atmospheric effects in the Cracow St. Catherine panels, and he also sees Danube School influences that suggest Kulmbach actually relocated to Cracow. In general, over his relatively short career, it is the consistency of Kulmbach that impresses, rather than a pronounced development. He replicated the same designs several times, and a number of works have been seen as workshop. Weniger makes a good point about working method. In contrast to Dürer, Kulmbach used rapid, loose, surface brushwork with visible corrections in layout but local color and modelling details only in later layers. Thus, Kulmbach could readily be delegated even prestigious work by busy Dürer. A final Weniger hypothesis builds on Johan Neudörffer’s report that Kulmbach apprenticed with Barbari to surmise that the artist, like Dürer, might have visited Venice itself, whence he adopted both rich coloration, spatiality, and atmospheric effects. But Barbari also worked as a court artist in Germany, where that connection more likely occurred.

The importance of St Sebald’s engages Gerhard Weilandt. He reconstructs a carved 1519 Madonna in the Sun shrine with flanking painted angels by Kulmbach (detached; five of six extant) as an ensemble. Closed, the panels presented a central Annunciation, flanked by Joachim and Anna, the Virgin’s parents before a landscape. Of course, Weilandt also addresses the Tucher triptych epitaph and its site within the framework of that patrician family’s complex on the north ambulatory and its chosen family patron saints. Comparison with the Berlin composition drawing by Dürer for the triptych reveals subtle changes by Kulmbach as well as its large, three-part relation to the nearby Volckamer Passion reliefs of Veit Stoss and contrast with earlier painted epitaphs.

Isabella Sturm and Teget-Welz detect a hidden aspect of Kulmbach’s output, his early collaboration with other, anonymous Frankish painters: the Master of the (Erlangen-)Bruck High Altar (1508-18) and the Master of the Former Fürth High Altar, possibly a documented Nuremberg artist, Hans von Heidelberg. More directly, Stefan Roller draws comparisons with the figural carvings of Nuremberg sculptor Master George (Jörg), whose interactive figures of a 1510 St Anne Altarpiece in St. Lorenz, Nuremberg, has Kulmbach painted wings. This leading, if neglected local carver, perhaps identifiable with Kulmbach contemporary Georg Herb (1506 citizen), is given an oeuvre here. Roller also notes a Kulmbach drawing for an altar shrine (British Museum).

A major output of Kulmbach drawings, around one-third of them, was devoted to stained glass design, magisterially surveyed in the essay by Hartmut Scholz with 50 illustrations, many showing the windows in color. These designs range from entire window ensembles for St Sebald’s (including a 1514 Maximilian commission, figs. 39-40 and Margrave’s window, figs. 41-42) to isolated individual roundels and quatrefoils in ink, whose surviving glass is illustrated. During the teens, Kulmbach was as productive in this realm as any other contemporary German artist, partly because of Dürer’s absence in Italy and the departure from Nuremberg of both Hans Schäufelein and Hans Baldung.[1] Most were executed by the specialist workshop of Veit Hirsvogel the Elder, though of course the cartoons are now lost. But Kulmbach’s individual forms emerges throughout. Subsequently, his leadership position in Nuremberg stained-glass design fell to Sebald Beham.

The volume closes with two catalogues: first, Christina Hofmann-Randall’s discussion, with concordance, of Kulmbach drawings and copies in the Graphische Sammlung of the Erlangen-Nuremberg University; then, Teget-Welz and Elisabeth Dlugosch present the varied drawings on view in the accompanying exhibition, which includes Kulmbach’s contemporaries, also represented in copies, and clusters of works by Wolf Traut and Georg Pencz, among others.

While any exhibition offers only a partial glimpse of an artist’s output, the essays of this well-researched volume complement the actual display and provide up-to-date soundings of this talented painter, draftsman, and glass designer. Much work remains to be done to define the Meister um Albrecht Dürer, but for now Hans von Kulmbach emerges as the clearest artist, ably presented in this handsomely produced volume by Manuel Teget-Welz and Hans Dickel.

Larry Silver

University of Pennsylvania

[1] Barbara Butts and Lee Hendrix, eds., Painting on Light. Drawings and Stained Glass in the Age of Dürer and Holbein, exh. cat. (Los Angeles-Saint Louis, 2000), esp. pp. 134-73,