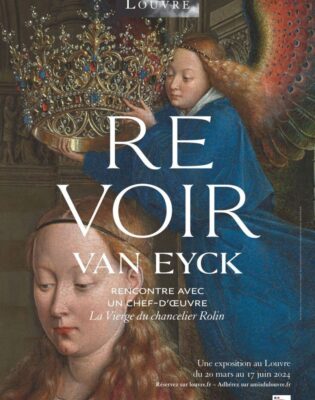

Entering the recent Louvre exhibition dedicated to the restored Virgin of Chancellor Nicolas Rolin by Jan van Eyck came with a sense of occasion, even drama. The narrow banners flanking the doorway isolated the Chancellor in prayer on our left and the Virgin and Child at right, so that we walked between them as if into the painting itself, which stood at the heart of the gallery. There was no slow build for this show; the star welcomed visitors from center stage in the company of more than sixty works convened to help illuminate it.

The light for which Van Eyck is best known is reflected or refracted from mirrors, metal, jewels, textiles, water, and other meticulously realized surfaces, but in the Rolin panel the strongest light pours forth from the distance, describing mainly itself. Jan accomplished this not simply by including abundant sky, but even more by framing it in three stone arches. The shine is brightened by their contre-jour effect and the material profusion of everything else surrounding the lambent center. The airy daylight is especially vivid for everyone who knew the picture through the yellowed varnish that had dimmed and flattened it for centuries. Of the many gifts of this intelligent exhibition, none is greater than the work of curator Sophie Caron, conservator Annie Hochart-Giacobbi, and their colleagues to reveal the paint itself, which had in fact weathered the centuries very well.

The restored reverse of the panel, which was painted (like several others by Van Eyck) to resemble colored jasper or marble, is astounding. It had been so damaged and darkened that the Louvre traditionally displayed the panel on the wall. This is unlikely to happen again, given the galaxy of green, yellow, and other colors that has emerged. None of the reproductions I have seen online or in the exhibition catalogue capture the paradoxical liveliness of this stone. It is arresting to realize that Jan van Eyck, whose conjuring of spaces, nature, and intricately crafted materials often seems boundless, could test the outer limits of illusion in his depiction of a flat, hard surface that churns and sparkles like water.

The exhibition’s title, Revoir Van Eyck, invited fresh observation of much more than rejuvenated colors and unprecedented technique. The other works presented were organized around six themes: Encounter, Portraits, Architecture, Landscape, Garden and Small Figures, and Two Functions for One Object? Each cluster brought productive reflection on aspects of the Rolin painting along with reciprocal illumination of the other works themselves, which ranged widely in medium and function. The first category included introductions to the Virgin of other powerful patrons, including Jean de Berry and Margaret of Cleves, in their renowned books of hours from Brussels and Lisbon (cats. 2-3). Less expected and in some ways more stimulating was Jacopo Bellini’s dreamlike Virgin of Humility with a Prince of the House of Este panel (cat. 5), painted around the same time as Van Eyck’s for the Chancellor. For many visitors, the highlight of this section was the Van Eyck painting of the Virgin and Child long known as the Lucca Madonna (cat. 7), which was being exhibited for the first time in the modern era anywhere but Frankfurt, where it entered the Städel Museum in 1850. It was startling to realize that this direct encounter between the observer and the Virgin in an enclosed room occupies a panel only slightly smaller than Rolin’s, which offers a scene as expansive as the Lucca Madonna is intimate.

Among the nearby portraits, the Chancellor would no doubt have been pleased to see his own likeness repeated in two works by Rogier van der Weyden: the presentation page of the Chroniques de Hainaut (cat. 11), where he stands at the elbow of the duke and therefore the heart of the Burgundian court; and the panel featuring Rolin from the exterior of the immense Last Judgment polyptych from Beaune (cat. 10), alas unaccompanied on the trip to Paris by the corresponding panel of his better half, Guigone de Salins. He presumably would have recognized his fellow Burgundian luminary Baudoin de Lannoy, who attended the exhibition in Van Eyck’s small portrait from Berlin (cat. 9). Whether or not Rolin knew the unidentified man in the riveting Campin(-esque?) portrait from the Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection (cat. 13), no one could regret its presence.

Sacred encounters and portraiture came together in the section on function. Building upon recent scholarship by Douglas Brine and others, the exhibition and Caron’s probing catalogue essays (“Vision de loin: une épitaphe pour Nicolas Rolin,” and “Vision de près: le voyage intérieur de Nicolas Rolin”) assert that the relatively compact Virgin of Chancellor Rolin was not made as an altarpiece, as is sometimes assumed. The earliest record of it, in the chapel of Nôtre-Dame-du-Châtel in Autun, dates only to 1748, not long before its arrival at the Louvre in 1800. While it had most likely been in the Chancellor’s home town in the fifteenth century, it might not have been installed in the church before Rolin’s death in 1462. During his life, the ca. 1435 painting may have been a portable devotional object well suited for a diplomat with residences in several cities. Individual prayer and public memorial are thus proposed as the dual functions explored in one of the exhibition’s thematic nodes. This made for an especially varied group of works. For private devotion, examples included books of hours, a painted diptych (the Louvre’s Eyckian grisaille Annunciation, cat. 53), a carved prayer nut (cat. 50), and a small portable altar (cat. 52) with a porphyry surface (common among such altars) that the Rolin panel’s marbled reverse might well have evoked. Memorial imagery was represented mainly by two early fifteenth-century stone epitaphs of a sort likely familiar to Van Eyck and Rolin (cats. 60-61). Both depict eternal prayer to the crowned Virgin and Child.

The three other themes (Architecture, Landscape, Garden and Small Figures) invited us – as Van Eyck himself did – to pay at least as much attention to everything else in the world he created. While each sharpened focus on several facets of Van Eyck’s invention in the Rolin panel, they also brought important works that are not always regarded chiefly for these aspects. When the Washington Annunciation (cat. 18) travels to an exhibition it is usually as a core piece of Van Eyck’s relatively small surviving oeuvre. Here, it was foremost a key example of the pervasive, varied, and deeply meaningful roles of architecture in his art. Landscape, which in the 1430s did not yet exist as an independent subject of European painting, stepped forward from books of hours, most notably in the Flight into Egypt from the Boucicaut Hours (cat. 19); the Turin-Milan Baptism of Christ (cat. 23); the famous though still puzzling Eyckian drawing often referred to as the “Fishing Party” (cat. 22); and several canonical early Netherlandish panels, including the Philadelphia version of Van Eyck’s St. Francis Receiving the Stigmata (cat. 24), the Dijon Nativity attributed to Robert Campin or his circle (cat. 25), the St. Catherine diptych (Vienna) and St. George (Washington) attributed to Rogier van der Weyden (cats. 27-28), and the Petrus Christus Virgin and Child with St. Barbara and Jan Vos from Berlin (cat. 30).

If Garden and Small Figures (petits personnages in the catalogue and petits guides on the wall text) seemed at first like a less natural category than the others, it also reminded us just how central this combination is to the Rolin painting, and not only for its place in the middle of both the picture plane and its depth. Each of the two men with their backs turned to the Virgin, Chancellor, and us sees something that the other does not. With no signs of prayer, work, or motion, they are occupied entirely with observation and perhaps conversation in a garden full of flowers and birds. It is no wonder that they have always attracted, surely by design, attention far out of proportion to their less than 4-centimeter stature. Their closest cousins are a man and woman at the garden wall in Van der Weyden’s roughly contemporaneous St. Luke Drawing the Virgin, represented in the exhibition by the Bruges version of the painting. The fascinating kinship between the masters’ compositions is broached from different angles within useful catalogue essays by Philippe Lorentz (“Le Chancelier, le peintre, et la Vièrge: Genèse d’un chef d’oeuvre”) and Pierre-Olivier Dittmar (“Le génie des lieux”). The Rolin garden and its fauna brought others from artists working further afield, including Cologne, Paris, and northern Italy, most notably in drawings of rabbits and peacocks by Pisanello and his circle (cats. 35, 37), and an especially magnificent peacock painted by Belbello da Pavia in the ca. 1434 Breviary of Marie de Savoie (cat. 39).

About half of the deeply researched, amply illustrated catalogue is dedicated to entries for the individual works. They begin with cat. 2 (the Très Belles Heures de Jean de Berry), presumably because the rest of the book so richly explores cat. 1. Any scholars wishing for a more standard entry for the Rolin panel will be grateful for the excellent, concise account of technical findings by Élisabeth Ravaud and Patrick Mandron (“Étude matérielle de la Vierge du Chancelier Rolin”). Among the most intriguing discoveries are dowel holes almost 13 cm deep at the top and bottom edges of the panel. There appear to have been two for each of the three vertical planks, approximately evenly spaced above and below. The authors note that few if any other fifteenth-century paintings reveal this preparation of a support, which could have been devised to allow freestanding display of both front and back. Detailed reports and imagery of the examination and restoration are available separately from VERONA (Van Eyck Research in Open Access), which is online at Closer to Van Eyck, the invaluable, still-growing resource that documents the ongoing study and restoration of the Ghent Altarpiece.

The drama of entering the gallery was enhanced by a slim border of daylight from a window behind the central work. The wall that blocked it allowed the picture its own full glow. Visitors drawn around that corner toward a real vista behind Van Eyck’s painted one also found a video screen looping “une méditation dans le paysage” offered as an immersive, high-magnification stroll in the distance. It was a compelling focus on craft that allows minute strokes and dots of pigment to become a moment in a day in many lives on a bridge, in boats, at church, along streets. More importantly, it sent us back to the painting itself, where a mesmerizing exchange of distance and proximity is now far more alive than it has been in centuries.

Revoir Van Eyck encourages us to see the artist not just again, but anew. The conservation, exhibition, and catalogue are towering contributions to a surge of recent work on the artist. Will there ever come a time when we find nothing new in these paintings, which were designed to draw and hold one close as none before them had ever done? The teeming worlds on both sides of the Virgin of Chancellor Rolin suggest that we have a long way to go.

Alfred Acres

Georgetown University