Anyone who has had the singular pleasure of making a Riemenschneider cultural crawl to the small towns in Franconia where his giant altarpieces are preserved in situ will appreciate the benefit and delight of this important new volume of collected essays. The co-editors are specialists in both the artist and the limewood medium. Boivin, Associate Professor at Bard College, has just published her Riemenschneider dissertation on the great Holy Blood Altarpiece in Rothenburg (Penn State Press, 2021). Bryda, Assistant Professor at Columbia, has earned his chops with a major Art Bulletin article (2018) about the wooden cross of the Isenheim Altarpiece, extending his innovative Yale dissertation on late-medieval German cultural associations with wood and the vegetal. Both scholars also performed the unsung service of translating numerous German texts by the volume’s contributors. The volume they have assembled makes important, albeit sometimes conflicting, new contributions to knowledge, so these essays will be discussed individually.

Certainly, Tilman Riemenschneider (active ca. 1483-1531) has not been neglected, either in German or in English. One major exhibition of his sculpture was mounted in Washington and New York (1999) by Julien Chapuis, who discusses the opposite experience to this book—about both that exhibition plus current museum installations of detached sculptures in Munich and Berlin–as the first essay of this volume. There he stresses the issue of showing an object’s original height. That exhibition catalogue featured essays by an international all-start cast (including Hartmut Krohm of the Bode Museum, whose obituary introduces this book, dedicated to him); it also prompted a companion volume (2004) from a follow-up National Gallery symposium.

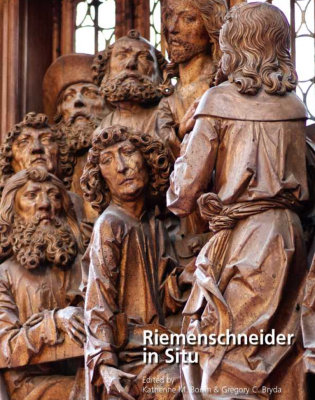

But what sets this new book apart is its emphasis on so many aspects of works studied in relation to their site, particularly at Creglingen’s Church of Our Lord as well as Rothenburg. After beginning with a focus on the unusual Maidbronn Lamentation (including the self-portrait of the artist as Nicodemus, discussed previously by Corine Schleif), an Introduction by the co-authors outlines the contours of the volume, drawn from a 2017 conference. Part One, Place and Placement, considers the locations themselves, while Part Two, Dynamic Environments, discusses relationships of the sculpted ensembles with other media in their churches. Part Three focuses more closely on Surface and Composition. Taken together, these essays often revise received knowledge about Riemenschneider altarpieces, reviewed (along with the pendant Bamberg Cathedral tombs) in the historiographic first essay by Jeffrey Chipps Smith. With the notable exception of Michael Baxandall in 1980, earlier scholarship has usually analyzed all these sculptures in isolation from their original, individual environments.

Boivin’s important synoptic study (“Topography of a Style”) centers, appropriately, on Rothenburg but also considers other regional locations (with map) and patterns of patronage in Franconia, especially across the bishopric of Würzburg. There the Riemenschneider house style, sorted according to material of stone or wood as well as location and cost, varied according to local socio-political networks. In Rothenburg alone, no fewer than nine altarpieces were installed, though other cities commissioned different kinds of works, including city hall decorations (Ochsenfurt).

An extensive material study by Volker Schaible of the Creglingen Assumption Altarpiece leads to his startling, revisionist assertion that the work did not originate for its current site, but rather once sat (as of 1496) on the lay altar at the same St. James’s church in Rothenburg itself, moved after a 1587 renovation there; this claim tallies with new dating for the supporting beams of the Creglingen shrine. After all, its Assumption centerpiece and rosary orientation do not even accord with the newer church’s dedication to Our Lord. Because it also participates in the newer, open shrine instead of the closed boxes of previous retables, Creglingen would take an earlier place in the oeuvre of Tilman Riemenshcneider, i.e. between the Magdalen Altarpiece of Münnerstadt (1492) and the Holy Blood retable of Rothenburg (1499-1505). Part One ends as Matthias Weniger complements Chapuis in discussing the Bayerisches Nationalmuseum’s reinstalled Riemenschneiders, featuring the remains of the Münnerstadt Altarpiece, in relation to their varied original appearances.

Part Two begins with a reminder by Johannes Tripps about the multi-media effects of altarpieces in their original locations as part of liturgical performances. Sometimes, using movable parts or descending elements, they even performed active roles in creating biblical scenes, using both space and light effects, particularly after the shrines were perforated for backlighting. Thierry Greub applies this same approach boldly to the Holy Blood Altarpiece in Rothenburg. He suggests that the work was originally placed in the east from the central nave of St James’s, thus facilitating equation of the image with the Mass itself, represented as instituted on the altarpiece (though a different location undercuts Michael Baxandall’s time-sensitive discussion of shifting light at the retable’s current location). Tripps notes that the problematic central emphasis on Judas by Riemenschneider obscures the fact that Judas was a removable figure, which could be eliminated from the scene except during Holy Week (One also thinks of Dürer’s unusual 1523 Last Supper woodcut, another later narrative moment without Judas).

The multi-media focus of Part Two shifts to Creglingen in the next two essays, which contest Schaible’s study. Mitchell Merback emphasizes the theological significance of the Assumption theme, both for its Eucharistic setting—within his studies of German host miracle sites–and for Marian grace through intercession. He also notes the empty space below Mary as equivalent to the Virgin’s empty tomb (Of course, if one accepts Schaible’s claim above of a Rothenburg origin for the altarpiece, some specifics about Creglingen dissolve). Tim Juckes considers Creglingen’s surrounding interior decorations, including side altars, as ensemble complements to the Assumption Altarpiece, while presuming that, “given the lack of evidence that it stood anywhere else” (pace Schaible; p. 248 n. 61).

Part Three’s object-centered studies begin with Krohm’s essay on how the original lighting conditions shaped perceptions of Riemenschneider folds, not only as graphic or two-dimensional (as suggested by Baxandall) but also as shifting substances under changing daylight (cf. Baxandall on Rothenburg), “a continuously unfurling liveliness, the actual presence of a saint in the sacred place” (p. 262). The same effect applies to Veit Stoss figures, whose abstract folds convey a sacred aura. Ruth Ezra also invokes Stoss folds in engraving and carving as models for Riemenschneider’s Detwang Resurrection (originally at Rothenburg), as shared forms between these two master sculptors rather than contrasting signature styles.

Riemenschneider is most often celebrated for his monochrome, unpainted “raw” [ruh] surfaces. Georg Habenicht, author of a dissertation and a 2016 monograph on that subject, revisits this phenomenon through both the Apostles Altarpiece (Heidelberg) and documents. He notes its patronage in Windsheim by widow in 1509 and its original painting by a local but then overpainted twice before being restored as monochrome. Such highlights of paint over priming [Fassung] adorned almost all sculpture surfaces, but sometimes suffered delays, including the Reformation interruption. Later restorations, removing deteriorated color, have shaped our vision of works, just as in the case of ancient sculptures. In short, painting was expected. Yet the next essay by Michele Marincola and Anna Serotta uses a noninvasive imaging technique (Reflectance Transformation Imaging, or RTI) to discover that sections of the Creglingen Altarpiece surface were never gefasst, or glazed, let alone colored, though further full examination remains.

The final essay by Assaf Pinkus discusses a less familiar work: the Last Judgment portal of Bern Minster (1460-85), carved by a Riemenschneider apprentice, Master Albrecht of Nuremberg as well as a local Bernese, Erhart Küng (act. 1456-1507). This dense composition recalls Gothic facades in full color. Pinkus considers its vertical layout as a process of compilation from painted models of the theme, derived largely from Küng’s Netherlandish-Westphalian origins, but used for new portal emphases, notably the central figure of St. Michael in gilded armor.

A brief afterward by Oliver Gussmann reprises Rothenburg’s Holy Blood Altarpiece, but as a contemporary experience—both religious object (in a Lutheran church) and tourist attraction. Examining a guest book and TripAdvisor along with church tours, he marks in situ responses to this powerful work and the difficult gap separating medieval rites from modern visitors.

As always, Harvey Miller production values and extensive color illustrations accompany these important contributions richly. With this volume’s own internal arguments about Creglingen and its revisionist interpretations about Rothenburg, clearly Riemenschneider scholarship is in a volatile but fertile moment of reinterpretations and new methodologies. Thanks to the efforts of editors Boivin and Bryda, these original, thoughtful essays provide essential and stimulating enrichments to our understanding of Tilman Riemenschneider projects.

Larry Silver

University of Pennsylvania