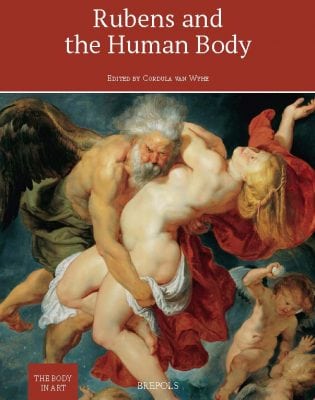

The book under review is the third in a series of Brepols monographs addressing the human body in early modern visual arts. Given the stated aim of this series – to explore new approaches and methodologies in the representation of the body, as shaped by conventions, beliefs, and values within a specific socio-historic context, a volume centering on Peter Paul Rubens could not be a more appropriate choice. For it was Rubens, more than any other artist of the early modern era, with the possible exception of Michelangelo, who used the human body to speak of some of the most complex and wide-ranging ideas about the boundaries between the corporeal and the spiritual. Male or female, young or old, sensual, or stoically firm under the extremes of passion, the human body was his most copious signifier and key figure of his visual rhetoric.

The background of this welcome addition to Rubens scholarship is a 2010 conference organized by Cordula van Wyhe, where most of these essays were first presented as papers. As she observes in her excellent Introduction, both that conference at the University of York and this volume were motivated by a surprising lacuna in the literature concerning the Rubensian body. Yet, as she also notes, this monograph does not aspire to be “exhaustive or orderly,” nor show a “unity of critical approach.” (p. 35) Rather, it presents “cross-referential readings” informed by various areas of interest, to “stimulate the discussion of a panoply of viewpoints.” (p. 35)

The contributions to this volume live up to this goal both in terms of the variety of topics and modes of inquiry. Van Wyhe herself sets the stage in the introduction by drawing on three different possibilities of looking at the Rubensian body which have not been sufficiently explored to date: humoral theory, the early modern connections between pictorial and medical knowledge, and the rhetorical conventions of the period, especially the idea of enargeia and its classical (specifically Aristotelian) origins. The first contributor is Andreas Thielemann, whose untimely passing away in 2015 led his colleagues to dedicate this volume to his memory. His essay revolves around the well-known, fragmentary theoretical text On the imitation of statues, widely considered as Rubens’s most important verbal exposition on the body. Like earlier scholars who had written on this manuscript (reproduced in Latin and English in an appendix), Thielemann highlights its theoretical underpinnings, which range from classical ideas on imitation to the rhetorical premium on brevitas associated with Lipsius, or the contemporary discourse on depiction of flesh among theorists like Lomazzo. However, as he significantly points out, the artist’s epistemology was fundamentally based on experience.

Rubens’s stated goal in the treatise On the imitation of statues – to transform his ancient marble models into living bodies – is also addressed by Anne Haak Christensen and Jørgen Wadum in an essay on the technical aspects of his painting style. Specifically, they attend to the ways in which Rubens’s theoretically informed painting technique – especially his use of particular pigments and layering modalities in the depiction of “flesh,” influenced that of his follower and rival Jacob Jordaens.

The relevance of the medium as such is also foregrounded in Joost vander Auwera’s essay. He returns to another oft-mentioned statement by the artist – his avowal that he is much better suited to working on a large, than a small scale – to suggest its possibly Aristotelian underpinnings. As he points out, scale is especially pertinent to the depiction of human figures, which relates both to classical notions about mimesis and rhetorical decorum. At the same time, while large format may be especially efficacious in moving and instructing an audience, the author also reminds us of the market conditions that played a role in Rubens’s ambition as a painter on large scale. Notwithstanding Auwera’s excellent points, his essay essentially reaffirms Rubens’s sensitivity to theoretical ideas and the art market, prompting us to think of ways in which one could expand on this inquiry towards a fuller understanding of his singular power to elicit emotional response through those life-size or larger-than-life-size bodies.

Two other scholars, Suzan Walker and Margit Thøfner, do so by attending more closely to what makes Rubens not just a man of his time, but truly exceptional. Walker looks at his self-conscious defiance of the rule of pictorial decorum in representation of the body in agony, while Thøfner focuses on his play with established iconographic codes, arguing that he could transform even such deeply coded figures as the lactating mother into self-referential metaphors about his own creativity. Of the two, Walker’s consideration of the ways in which Rubens “deforms” the agonized body is more persuasive. Thøfner’s alignment of the viscosity of milk and the painter’s pigments, needs, in the opinion of this reviewer, greater corroboration than the one she is able to provide in her imaginative take.

Nonetheless, both of these essays demonstrate the value of close looking, which also applies to the next contribution in this volume, by Karolien de Clippel. Her subject is another facet of Rubens’s visual intelligence, his striking use of drapery as a pictorial device to enhance the corporeality and the sense of movement of his figures. I only wish this analysis extended a bit further, to a discussion of his choice of colors of those draperies – especially the Rubensian red as a virtual index of his presence in so many of his paintings.

Another group of authors situate Rubens’s approach to the human body within the framework of the medical discourses of the period. An intellectual historian, Jacques Bos, provides a good overview of seventeenth-century psychology and its historic origins in neo-stoical and humoral theories. Lucy Davis continues in a similar vein by exploring the artist’s concerns with humoral imbalance, immoderation, and aging in a corpus of paintings on that most paradoxical of Renaissance characters – the drunken Silenus.

Katerina Geourgoulia complements these readings in an insightful analysis of one of Rubens’s most remarkable and understudied works – Pythagoras Advocating Vegetarianism. So does Elizabeth McGrath, in another of her typically erudite analyses of Rubens’s representation of Africans. Last but not least, Irene Schaudies returns to Jordaens to contrast his less subtle and more market-driven Bacchic paintings with the densely layered and semantically multi-faceted works of Rubens as his life-long model.

Joanna Woodall provides an effective summation of the main concerns of the contributors in her Afterword to this volume, highlighting the importance of “Nature” for our understanding of Rubens’s attitude towards the body/soul relationship. In this context, she draws attention to the need for further investigation of the interdependence of these two aspects of being, as manifested in the ways in which Rubens’s bodies transcend gender categories, or, for that matter, even the “binaries between self and other.” (p. 348)

This was the approach to the body/soul relationship that I was looking for in this volume, and which I hope to find in further studies on this far from exhausted subject. For, Rubens’s bodies do not fascinate as much on account of his technical bravura or knowledge of art theory, but because of his unruly melding of the sensual and the spiritual that defies explanation – whether in the satyress from the Munich Drunken Silenus as an archetype of a mother, or in that outstanding portrait of his wife, lover, and mother of his children in Het Pelsken.

Aneta Georgievska-Shine

University of Maryland – College Park