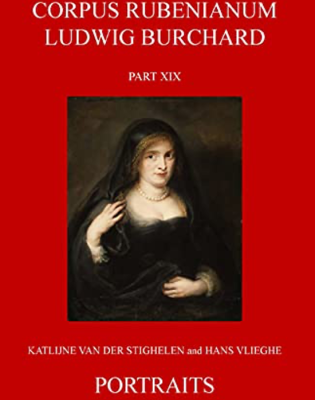

In the Corpus Rubenianum Ludwig Burchard four volumes are devoted to Rubens’s portraits. The first, by Frances Huemer, Portraits Painted in Foreign Countries, appeared in 1977, the second, by Hans Vlieghe, on Identified Portraits Painted in Antwerp, in 1987, the third (though numerically the fourth) by Konrad Jonckheere, on Portraits after Existing Prototypes, in 2016. This volume which catalogues Unidentified and Newly Identified sitters painted in Antwerp appeared in 2021. It comprises numbers 162 – 216 of the total catalogue of portraits. It is a collaboration between Hans Vlieghe and Katlijne Van der Stighelen. They are each responsible for about half of the catalogue entries but Van der Stighelen also contributes a long essay on “Rubens as a Painter of Portraits” which is a valuable survey of the entire subject. Rubens shared the contemporary view that portraiture was a lesser form of art and the personal view that it was a distraction from the far more important business of history painting. Van der Stighelen explores the reasons why Rubens undertook portraits, using telling examples: for personal or family reasons (for example, the Self-Portrait with Isabella Brant in the Honeysuckle Bower), for reasons of friendship (for example, the portrait of The Artist and his Friends in Mantua), in the hope of further patronage (for example, the portrait of Lady Arundel and her entourage), as well as court portraits (notably of the Archdukes) which were part of his role as a court painter. Also discussed in this volume is a substantial group of religious sitters – Van der Stighelen remarks that “He [Rubens] seems to have developed a predilection for portraits of pastors in Antwerp”- which presumably can be explained as a consequence of admiration for individuals (a number of whom were attached to St. Michael’s Abbey, where his mother was buried) and his own faith. After his return from Italy in 1608 he reverted, as Van der Stighelen notes, to a more traditional portrait format while Van Dyck proceeds to revolutionize portraiture. Rubens does eventually incorporate some of Van Dyck’s innovations and a section of Van der Stighelen’s essay contrasts the portraiture of the two artists. She writes of the sculptural quality of Rubens’s portraiture, which is very different from Van Dyck’s style, but could have extended this idea further. Rubens’s close study of antique sculpture and Van Dyck’s remarkable lack of interest in the antique is the key here and a profound difference between the two.

The catalogue entries are well-argued and both attributions and deattributions largely convincing. A number of the latter feature the asterisk which is now used by contributors to the series to indicate those paintings whose attribution to Rubens by Burchard is not accepted. There are seven such asterisks and three rejected attributions and in almost every case I would agree, although the Barber Institute Carmelite (cat. No. 168) is by Rubens in my opinion. There are a number of outstanding individual entries – for example, the identification by Van der Stighelen and Jean Bastiaensen of the goldsmith Robert Staes and his family in the portrait group in Karlsruhe (cat. No. 176), a remarkable piece of research published at length in The Burlington Magazine, 2020. Another excellent entry by Van der Stighelen is A Woman with a Veil (cat. No. 206) in the Metropolitan Museum of Art whom she (tentatively) identifies as Helena Fourment. The authors accept the attribution to Rubens and the identification of the near-grisaille portrait of Clara-Serena Rubens (cat. No. 212) which was auctioned in London in July 2018. This portrait had been deaccessioned by the Metropolitan Museum in 2013. It is a fine portrait by Rubens of his eldest daughter, possibly rendered in grisaille as a memorial to her. Van der Stighelen wrestles with the Portrait of an Old Man (cat. No. 178) sometimes said to be Thomas Parr who fascinated contemporaries as he was supposed to have lived to the age of 152. Rubens, on his trip to Cambridge in 1629, is said to have possibly visited Parr in “nearby Shrewsbury.” In fact Shrewsbury is 142 miles to the west of Cambridge, a substantial detour. If it is Parr which is by no means certain, Rubens presumably based his portrait on an existing one.

There are a number of drawings catalogued here, although the rationale for their selection is by no means clear. They add significantly, however, to the value of the volume. There is, for example, a fascinating discussion of the well-known drawing in the Getty now identified by Thijs Weststeijn and Lennert Geesterkamp as Yppong, a Chinese merchant, on the basis of a drawing in the album amicorum of Nicolaas de Vriese.

There is much to admire in this volume, one of the most distinguished to have appeared as part of the Corpus Rubenianum project, of which the end is now in sight, largely because of the prodigious efforts of the much-missed Arnout Balis.

Christopher Brown

University of Oxford