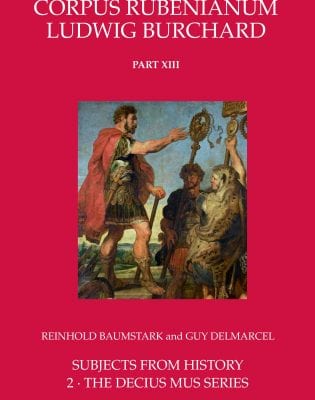

Rubens’s first commission for a monumental cycle of decoration was the Decius Mus series, the first of his four tapestry cycles and the subject of this two-volume study of monumental scope. The subject is a heroic drama in six scenes (plus an allegorical scene of Victoria and Virtus) about the legendary Roman consul Decius Mus, drawn from the ancient historian Livy’s account of his sacrifice in battle to save Rome. The six magnificent narrative canvases, Rubens’s grandest undertaking to date, are in the Liechenstein Collection, Vienna. The court chaplain in Brussels eulogized Rubens as “the most learned painter in the world.” The authors provide conclusive proof that the tribute was no hyperbole.

The identity of the patrons (“gentilhuomini genovesi”) for whom the two sets of Decius tapestries were to be woven (with different and precise dimensions) remains shrouded. Whoever chose the unusual subject in late 1616 – never before illustrated by such an epic cycle – it provided Rubens an opportunity to express his lifelong devotion to classical antiquity. The themes of virtus, pietas, and devotio – the underlying meaning of this story of self-sacrifice for the salvation of others – are explored in Baumstark’s first chapter, “The Subject and its Sources.” Its proto-Christian potential resonated with the devout Rubens. For Rubens there was no conflict between the ideals of ancient Rome and the Christian faith of New Rome. Rome remained Rome, a continuum of revelation.

Baumstark’s exploration of Rubens and classical antiquity, the subject of the next chapter (“Reconstructing the Ancient Past”) sums up the transformative aspects of Rubens’s study and quotations from antiquity as a process of translating – as his Italian Renaissance predecessors Mantegna, Raphael and Giulio Romano had done – “classical dignity and beauty into a Christian context, to adopt supreme images of the ancient past to invest them with new validity….” (p. 119). His analysis is elegantly reinforced by Kristin Belkin’s lucid translation from the German.

Baumstark’s concluding chapter (“Work in the Rubens Studio”) offers an illuminating account of Rubens as conductor of Europe’s most productive workshop before Bernini’s. The year 1617 was arguably Rubens’s busiest to date, and Baumstark speculates that Rubens may have farmed out the two final and grandest cartoons (the Death and Obsequies) to another studio to be worked up from his detailed modelli, which represent the largest and most highly finished of the oil sketches. He proposes Jordaens’s studio (p. 186) – and Jordaens himself as the primary painter of those two canvases. It is hard to imagine that Rubens would have assigned these most difficult compositions to a collaborator removed from the master’s immediate oversight. But if so, that might explain the highly detailed, finished quality of Rubens’s autograph modello for the Death of Decius (Prado, Madrid), which Baumstark describes as “an entanglement and staggered arrangement of figures and action as not seen before in Rubens’s work” (p. 204). Rubens would have wanted no ambiguity or lack of clarity in the heroic task of enlarging his composition into the full-scale cartoon. What I consider untenable is Baumstark’s hypothesis that Rubens delegated not only the cartoons but the execution of the final oil sketch modelli of the two concluding scenes to a collaborator (p. 208). I can more easily imagine Mozart delegating to a colleague the orchestration of the final act of Don Giovanni.

Rubens never delegated the painting of the preparatory oil sketch to an assistant, even one as talented as Van Dyck or Jordaens. In every subsequent cycle – from the thirty-six Jesuit Ceiling paintings to the Torre de la Parada, which required over sixty oil sketches as modelli to work up into finished paintings – Rubens painted the oil sketch himself. Baumstark cites the large modelli (executed by studio assistants with the master’s final touches) for the later Achilles tapestry cycle as analogous. But in the case of the Achilles tapestries each of those large modelli was closely based on an original autograph oil sketch by Rubens, and the qualitative gulf between the two is readily apparent (see my HNA review of the 2018 Prado – Rotterdam exhibition of Rubens oil sketches). There is nothing in these two modelli for the most complex of Rubens’s Decius tapestries to suggest the hand of Jordaens – or any other assistant. Incidentally, the single half of the snaffle bit on Decius’s horse represents not (as Held once suggested and Baumstark cites, p. 137) an error unworthy of the equestrian Rubens but rather an example of his economy: only the foremost bit is delineated so as to render its curvilinear form with utmost clarity, unblurred by a shadow image (which was easily replicated in the final cartoon).

Baumstark is surely correct in assuming that Rubens preceded his modelli with either “first thought” drawings or cursory oil sketches, but there is no evidence that he prepared each modello with a distinctive bozzetto as he did for the Jesuit Church, Medici, and Eucharist cycles. Those three commissions had royal or ecclesiastical patrons, and those bozzetti, however cursory and spare in color, were compositionally set so as to serve as preliminary models for discussion with patrons or their advisors.

Baumstark has in this volume reversed his original belief – shared by the majority of Rubens scholars as well as by his co-author Guy Delmarcel – that the full-scale studio canvases served as cartoons for the tapestry production, either as direct cartoons for the weavers or as exact models to be copied or transferred onto paper by cartoon specialists at the tapestry workshops and cut into strips. Instead, Baumstark here conjectures that Rubens’s assistants painted duplicate full-scale enlargements: the Liechtenstein canvas and, side by side, an identical now-lost paper cartoon. But there was no need for the latter to be made by Rubens’s already overcommitted studio once the former existed. Transferring designs to paper cartoons was a specialty of tapestry workshops.

Back in 1982 at the International Rubens Symposium (Ringling Museum, Sarasota) Baumstark provided the most compelling argument in favor of those Liechtenstein canvases being the “alcuni cartoni molto superbi” that Rubens described in his 1618 letter to Sir Dudley Carleton. If not – if those canvases instead represent, as Baumstark now proposes, studio works painted in addition to the paper cartoons – then Rubens would have been able to give Carleton their identical dimensions without having to inquire with the Brussels weavers to whom the cartoons had been consigned. Baumstark is surely right in assuming that their more permanent medium (oil on canvas) reflected – as he quotes this reviewer (p. 228) – Rubens’s intention that they “have a life apart from the tapestries for which they were designed.” His theory that they may have served as permanent decorations for the Tapissierpand, Antwerp’s tapestry market (pp. 232-234), is compelling. But in no way does it negate the initial function of those canvases as full-size models to be copied on the paper cartoons at the tapestry workshops and cut into strips for the weavers, as Delmarcel affirms (p. 243). Rubens was the master of recycling: the afterlife applied to his art as well as his faith.

Delmarcel’s model chapter on the tapestries themselves is a most welcome addition to the literature on Rubens’s designs for tapestries. He notes that despite the many extant re-weavings of the Decius series the two editiones principes – the original tapestries sets which Rubens was to inspect – have yet to be identified. One may only hope that they remain safe, if hidden, in some Genoese palazzi.

The catalogue raisonné (vol. 2) that concludes the study is as thorough as it is illuminating. Beside my rejection of Baumstark’s ascribing Rubens’s modelli for the Death and Obsequies to the workshop (supra), I agree with Held (Oil Sketches, 1980, I, pp. 29-30) that the modello for the Consecration (Neuburg) is a copy of a lost original (p. 81). Nor do I see the two drawings after Rubens (figs. 43 and 60) as possible reflections of lost bozzetti. Fig. 43 is surely sketched after the modello to which it so closely corresponds. Fig. 60 was likely made from a finished tapestry, as Baumstark himself suggests (p. 80). Likewise, the Rubens Cantoor drawing (fig. 122) corresponding “precisely in all its details with the modello” of the Obsequies (vol. 1, p. 201) cannot have been drawn from a hypothetical bozzetto simply on the basis of a stone step at the bottom left. The drawing is far too precise. That added detail represents no more than the anonymous draughtsman’s rationalizing that lower corner of the scene. One copyist’s invented step need not posit an additional step in Rubens’s design process.

What remains beyond doubt or debate is the enormous value of this two-volume addition to the Corpus Rubenianum and to future Rubens scholarship. It is as heroic as the story – and cycle – it treats so magisterially: Rubens-worthy!

Charles Scribner III

New York