The legendary drawings collection of the Albertina in Vienna, which includes peerless holdings of early Netherlandish drawings, was on glorious display at the Cleveland Museum of Art from October 2022 to early January. The Cleveland exhibit is now immortalized in this superb catalogue, a joint collaboration, like the exhibition, of the Cleveland Museum and the Albertina Museum. Of the 96 works shown in Ohio, 87 were from the Albertina. In effect, the Cleveland exhibition was a showcase for many of the Albertina’s sixteenth-century Netherlandish greatest hits, together with less-familiar but equally fascinating and relevant works. For an American audience, this loan exhibition was a special event.

The essay by curator Emily Peters, subtitled “Drawing as Communication in the Urban Context,” directly addresses the catalogue’s title and focus: the relation between sixteenth-century Netherlandish drawings and the new centrality of urbanism, which emphatically defined the geographical region and its century. Peters emphasizes, for example, that population growth in the Southern Netherlands increased at approximately three per cent per annum between 1500-1550. This uniquely Netherlandish reality, especially in major urban centers like Antwerp and Haarlem, transformed the functions and meanings of drawing practices and subjects. As Peters highlights, the new urban context encompassed two distinct realms: the physical place of the city (urbs) and the social structure of the city (civitas). Both aspects are addressed in the drawings in the show, as Peters shows. Among the new subjects and strategies taken up by sixteenth-century draftsmen are the urban stagings of religious, historical, and mythological scenes; drawings devoted to town views and their associated landscapes; designs for church windows and altarpieces; and images planning the numerous Joyous Entries into cities. The latter served as a basis for the subsequent prints that insured a permanent, widely circulated record of these essential performances of civic and political identity.

Stephanie Porras’s essay addresses the subject of chiaroscuro drawings (drawings on colored grounds), although she opens her account by considering the new phenomenon of artists gifting their drawings (Dürer, Jan de Beer). She then lays out the varied functions of chiaroscuro drawings. For example, within model-books, these drawings were kept in the artist’s studio as a reference; and sometimes they were used to make a vidimus, the drawing presented to a client or patron for approval and / or contract. They might be used for a fully worked-up scale cartoon for a tapestry or church window. And smaller-scaled, finely finished chiaroscuro drawings might serve as records (ricordi) of a completed workshop design, a visual document for the artist’s studio. Above all, during this period chiaroscuro drawings were often used for roundel drawings to be traced, or else transferred by pricking-and-pouncing, to make silver-stained glass windows for domestic and religious settings. Porras concludes by discussing the likelihood that already in the early sixteenth century drawings were beginning to be collected as autonomous art works.

In her essay, Laura Ritter shows how, with the rise of Protestantism, representations of traditional Catholic saints, such as Martin, James, and Anthony, were reconfigured in drawings and prints to address the dangers and corruptions of contemporary urban life. The drawing sources for prints that generated these new constructions of civic identity often do not survive, but the engravings that support her thesis come mainly from the circle of Hieronymus Cock, the leading print publisher in Antwerp, well-known for his stable of draftsmen employees who designed his prints. The final essay, by Koenraad Jonckheere, concerns the difficult problem of theory. Although there was no established art theory as such in the Low Countries, in contrast to Italy, Jonckheere shows that by analyzing little-studied Catholic and Protestant tracts of the late sixteenth century about the image debate, their textual terms and principles argued for new, idea-centered approaches to image-making. Northern artists could adapt that conceptual, essentially theoretical framework for their practice of drawing along with other arts.

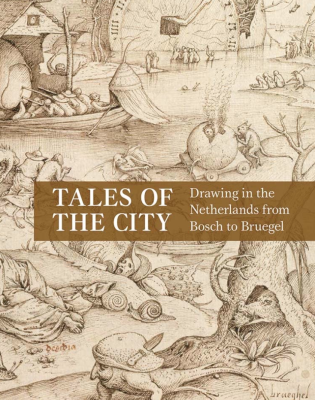

Drawings in the exhibition represent the catalogue’s subtitle: Bosch’s famous Tree Man (no. 4) and Bruegel’s equally famous Big Fish Eat Little Fish (no. 73), plus a second sheet by Bosch (no. 5) and three others by Bruegel (no. 74-76). The great coup of the Cleveland exhibition was the Albertina’s generous loan of Jan de Beer’s early sixteenth-century Tree of Jesse cartoon (nos. 28, 29). This fifteen-foot-high cartoon, made for an unknown church window, was divided horizontally in the middle years ago and framed as two individual works. Even so, each half comes to nearly 230 cm in height. To my knowledge, these huge drawings had never left the Albertina for a loan exhibition. Other well-known drawings on exhibit included three “naer het leven” drawings by Roelant Savery (nos. 57-59) and six drawings from the Netherlandish History (Belgica-Folge) series by Joachim Wtewael (nos. 91-96).

Most drawings clearly manifested the urban focus of the exhibit – city views, urban inhabitants, and the city as a setting for religious narratives. A remarkable and eccentric example of the latter is a beautiful Antwerp Mannerist chiaroscuro drawing of Bathsheba standing naked in a shallow bathing pool in the middle of an imaginary city square, surrounded by her servants; they converse or play music while one of them delivers King David’s letter (no.21). Occasionally, the urban thematic link of certain drawings is more indirect, yet these works still enhance the exhibition, such as Joris Hoefnagel’s pen and watercolor Grotesques (nos. 84-86) and beautiful self-portraits by Jacques de Gheyn II and Hendrick Goltzius (nos. 65, 66).

Those Americans fortunate enough to see the Cleveland show in its imported splendor should thank their lucky stars. The transatlantic loan of so many gorgeous Netherlandish masterworks from an unrivalled European collection is unlikely to happen again anytime soon, if ever. For this remarkable occasion, an enormous debt of gratitude is owed, chiefly to the Albertina, plus the organizers at the two museums and the catalogue contributors.

Dan Ewing

Barry University