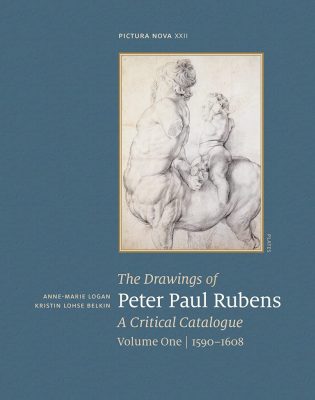

Anne-Marie Logan’s catalogue of Rubens’ drawings, which to public knowledge, has been a very long time in the making, in fact going back as far back as 1965, when she started collecting material under the aegis of Egbert Haverkamp Begemann. In 2005 she offered a taste of her research in the memorable exhibition of a selection of the master’s drawings, arranged in conjunction with Michiel Plomp, at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Although drawings are slowly being catalogued, subject by subject, as part of the ongoing series devoted to Rubens’ work in the Corpus Rubenianum Ludwig Burchard, this is the first time a catalogue of all his drawings, according to one scholar’s estimation, has been attempted and its fulfillment represents a milestone in Rubens studies. The first part, in two handsomely produced volumes, covers the early period in Antwerp followed by the eight years spent in Italy (1590-1608). Part two (1609-1620) and part three (1621-1640) will follow.

As Logan makes clear from the outset the attributions, and presumably the dating, are hers and hers alone. Kristin Lohse Belkin, no less qualified to make an informed opinion about the subject, has here taken on the responsibility of bringing the book to fruition, expertly editing the material. The result, both in manner of presentation and conclusions reached, is immaculate, providing full discussion of provenance, with interesting asides on collectors, literature and discursive comment on each drawing. Some of the last are of essay length, such as those devoted to the copies after Holbein’s Images of Death, the copies after Michelangelo’s Sistine Ceiling, the copies after the antique Laocoön and his Sons, and the artist’s Anatomy Book. The subject is full of difficult decisions, and Logan takes a cautious line, never hesitating to express uncertainty. One good point is the punctilious acknowledgement of differing opinions expressed by other scholars, so that one is presented with the full range of options. The catalogue is arranged in a precisely conceived chronology, even down to separating recto and verso when they are assigned different dates. In the accompanying volume every drawing is reproduced in excellent color, to which is added the very welcome bonus of illustrations of every work that Rubens has copied. The present reviewer is left with only one small wish, namely that indexes of subject matter and collections had been included.

Given the scale of the subject it is understandable that a list of rejected attributions is not given. But it is perhaps regrettable when it concerns Van Dyck, that often brilliant imitator of his master’s style of drawing, whose shadow hangs over the connoisseurship of Rubens’ drawings; it is often only a hunch which nudges an opinion one way or another. Logan touches on the problem by mentioning the case of The Massacre of the Innocents, in the Palais des Beaux-Arts, Lille, over which opinion is split between three scholars who believe it is by Rubens and three, including Logan, who think that it is by Van Dyck. Also not included in the catalogue are drawings by other artists retouched by Rubens of which there are legion, and which can be studied as a separate subject.

Logan is selective when dealing with identifiable copies after lost originals. In the case of the large group made by Willem Panneels in the so-called ‘Rubens cantoor’ in Copenhagen—its integrity in making such copies in Rubens’ absence is stoutly maintained—she only includes a number. Also omitted are copies after drawings originally in the destroyed Theoretical Notebook, or Pocketbook as it is often known, apart from the one or possibly two known originals which have survived. Very recently and therefore too late for inclusion, is the discovery of a third original double-sided sheet.1

Instead of prefacing the catalogue with an overview of Rubens’ practice as a draftsman, extended examples of which are, as Logan rightly points out, to be found in Julius Held’s book on the drawings2 and in her New York catalogue (2005), she has here contributed an introductory essay examining in considerable detail the history of Rubens drawings scholarship. It opens with volumes devoted to selections of Rubens drawings, starting with Rooses (1892) and continuing with Glück and Haberditzl (1908), Burchard and d’Hulst (1963) and Held (1986), all of which make a serious contribution to the subject. Following on are collection catalogues, exhibition catalogues, of which there have been numerous examples in recent years, and a selection of articles. Particularly commended are the discoveries of Michael Jaffé and Julius Müller Hofstede, and the iconographic studies of Elizabeth McGrath. It provides a record of an impressive array of scholarship, told here for the first time.

If you leaf through the plates in the second volume, you are forcibly struck by the fact that you are largely looking at Rubens the pupil rather than Rubens the master. Of the 204 entries well over half concern copies after other works of art (sixty-eight after the antique, sixty-four after other works of art) and only seventy-four original studies. (The apparent discrepancy in numbers is accounted for by the fact that several sheets have originals on one side and copies on the other side.) His very early work is almost exclusively limited to copies after Northern art, particularly after German prints. It is only on arrival in Italy, when he, apart from making copies after Michelangelo and one or two other Italian artists, turns his serious attention to many of the famous antique sculptures to be found in Rome, such as the Farnese Hercules, the Laocoön and the Torso Belvedere; in numerous sheets they are studied whole, often from different angles, as well as in varied details. He literally devours the sculptures, his copies to be put aside for future use.

Rubens only comes into his own as the draftsman we know when he arrives in Rome and draws such masterly pen and wash sheets as The Washing and Anointing of Christ’s Body (Museum Boijmans van Beuningen, Rotterdam) and The Descent from the Cross (Hermitage, St Petersburg). From then on there are a number of fine original drawings, culminating in the preparatory studies for the altarpiece for S. Maria in Vallicella (“Chiesa Nuova”), which completes his time in Italy and ends the volume. But for the full range of his draftsmanship one must await the appearance of the next part of the catalogue.

And finally the good news that the second part, covering the years 1609 to 1620, is in an advanced state of preparation and should be published before long.

Christopher White

London

1. A Satyr pleasuring herself against a Herm: after the Antique (recto) and Pentheus: after Daniele da Volterra (verso); the drawing is now in the Phoebus Foundation, Antwerp. (Balis in Staatsgalerie, Stuttgart, Becoming Famous Peter Paul Rubens. Exh. cat. by Niels Büttner and Sandra-Kristin Diefenthaler et al. 2021, pp. 157-165, no. 36, repr.).

2. Rubens: Selected Drawings, Mt. Kisco, N.Y.: Moyer Bell Ltd., 1986.