As the first in a series about Jan (and Hubert?) van Eyck’s Ghent Altarpiece (1432), this volume documents the research and conservation treatment of the exterior panels. It is undoubtedly an essential resource for scientists and conservators; however, I also urge art historians to read it cover to cover. It approaches the Ghent Altarpiece foremost from a material perspective, but also answers art historical questions in the context of its history of display, interventions, and conservation. The long list of authors shows that the research, examination, and treatment of such an important and complex artwork requires an interdisciplinary team. The Table of Contents also makes clear that the altarpiece is not only discussed in terms of its material parts; the reader seems to be guided through the experience of a conservator, as they unpack or “strip back” each layer of information, while considering the artwork as a whole.

Chapter 1, which explains the changes that happened to the altarpiece in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, is followed by chapters on: the frames and support (2), paint and polychromy (3), the conservation and restoration treatment (4), the Van Eycks’ creative process (5), the authenticity of the quatrain and the other frame inscriptions (6), imagining the original display (7), restoring in the public eye (8), an epilogue about implications and perspectives (9), and documentation (10). Each could be read as a stand-alone essay, but the reader would miss significant connections: for example, between the interventions that have occurred on different parts of the altarpiece, or the rationale that guided the conservation treatment. Some questions that were only partially addressed in an early chapter are fully developed in a later section. The frames, for example, feature in four separate chapters, which discuss their construction, their relationship to the oak panels, changes that have occurred over time, and the practicalities of their conservation treatment. These are necessary to comprehend how miraculous it is that despite – and sometimes because of – past interventions, the frames’ original polychromy has partially survived. The Van Eycks’ stone imitation, applied on top of a layer of silver leaf, is all the more remarkable when it is considered in the context of the altarpiece’s exterior.

The in-depth consideration of the frames also pertains to an ongoing art historical question addressed in Chapter 6, “The authenticity of the quatrain and the other frame inscriptions,” by Susan Frances Jones, Anne-Sophie Augustyniak, and Hélène Dubois. Illustrated as a foldout at the back of the book, the quatrain is reconstructed and reconsidered, with arguments supported by microscopic examination, high-resolution photography, paleography, and textual evidence. Although most chapters in the volume end with a discussion of results, Chapter 6 was one where a summary would have conveyed important conclusions. This is clarified in the epilogue by Cyriel Stroo and Maximiliaan Martens: “the discovery of the quatrain’s authenticity is nothing less than a coup de foudre in the discourse of art-historical research, for a long-standing debate can finally be concluded as we now can be sure that the quatrain was applied simultaneously with the polychromy of the frames” (354).

The quatrain has another important implication: it mentions that both Hubert and Jan van Eyck worked on the Ghent Altarpiece. Hubert’s precise role(s) in its genesis has long been debated: was he responsible for the concept, construction, drawing, and/or painting? Attribution is addressed in a section – “One painter – or several?” – within Chapter 5a, “The paintings: From (under)drawing to the final touch in paint,” by Marie Postec and Griet Steyaert. By illustrating and describing recurring painted motifs within the different parts of the exterior, they compare slight differences in handling, proportion, and color. In this section, the reader might feel empowered to draw their own conclusions about whether or not these motifs were painted by different hands. Ultimately the authors’ conclusion is expressed firmly on page 240: “Unless Hubert or an assistant was able to equal Jan in the art of underdrawing and in the spontaneity of pictorial execution, everything seems to indicate that these paintings were completed entirely by Jan van Eyck himself, from the laying down of the composition to the finishing touches.”

These two examples – the quatrain and the debated (co-)authorship – demonstrate how technical examination can shed light on long-standing art historical questions. Chapter 3, “Paint and polychromy: Chemical investigation of the overpaints” by Jana Sanyova and others, begins by comparing the types of analysis that were possible in 1950–51 – when Paul Coremans and his team conducted the first thorough scientific examination – to the technical advances available to scientists and conservators today. The most significant recent development is the adoption of non-invasive technologies that do not require touching the surface of the artwork; however, important information about materials and stratigraphy can still be obtained from the (re-)examination of microscopic samples. It is the combination of these micro- and macroscopic methods that provides a complete understanding of an artwork. (Specifics of some instrumental methods used to examine the Ghent Altarpiece are described on pages 78–79.)

The benefits of combining micro- and macroscopic examination methods is exemplified by the complex process of distinguishing original paint layers from later interventions, and the ultimate decision to remove the overpaint from large passages of the exterior of the Ghent Altarpiece. The clothing of Elisabeth Borluut and Joos Vijd had been almost completely overpainted, and the recent restoration treatment revealed Van Eyck’s original paint layer for the first time in centuries. Chapter 3 clearly describes and illustrates the ethical issues, the pros and cons of removing the overpaint, the steps in the removal process, and the possibilities and limitations of scientific examination methods. Although samples had revealed the presence of non-original layers on the surface, the extent of the overpaint only became clear when the paint was scanned with macroscopic X-ray fluorescence (MA-XRF) (see page 129, fig. 4a.19). This technology detects the chemical elements present in the pigments and produces an image that maps their distribution. MA-XRF was used as a visual tool to convince the International Committee, the stakeholders, and the public that removal of the overpaint was both visually desirable and safe for the artwork. The context of how these conclusions were reached is even more significant.

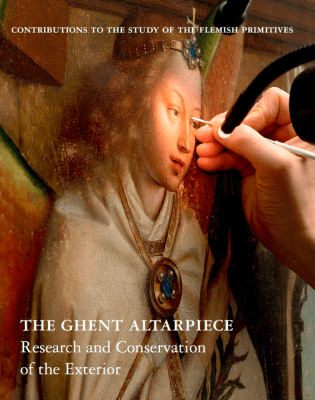

The photographs and illustrations in this book are of excellent quality. As a conservator, I inevitably wanted to zoom in further to explore their microscopic aspects. This is where the interactive website Closer to Van Eyck: The Ghent Altarpiece restored is a useful addition. If a digital version of this publication were to be considered in the future – perhaps following the publication(s) about the interior of the altarpiece – it is hoped that the illustrations could somehow be connected. The printed book has made great efforts to show the reader why this treatment was so necessary: at the end of the volume is a series of before-and-after photographs of each part of the altarpiece’s exterior. Within the chapters, technical images – like MA-XRF scans and microphotographs – are always clearly connected to the text, and labelled to indicate their location on the altarpiece. The figures are well chosen to demonstrate the progression of the treatment. For example, Chapter 4a, “Conservation and restoration treatment: The painted surface” (by Livia Depuydt-Elbaum and others), contains an image of the Prophet Zechariah that shows how yellowed varnish and other non-original layers were removed in stages to reveal the bright white interior of his ermine-lined cloak (fig. 4a.10). Work-in-progress photographs – like one illustrating the step-by-step process of applying and removing a gelled cleaning agent from the frame (fig. 4b.9) – are not common in publications, yet these are instructive for visualizing how and why the steps of the treatment were carried out.

The conservation treatment of the exterior was carried out in public view within the Museum of Fine Arts in Ghent. In Chapter 8, “Restoring in the public eye,” Bart Devolder candidly discusses the successes and challenges of this strategy. He also mentions the benefits and intrinsic issues of educating the public about conservation decisions and outcomes, and how this is a process that continually needs to be reassessed in the light of new findings and feedback.

It is important to remember that this volume only considers the exterior panels of the Ghent Altarpiece. The authors resist drawing too many conclusions about the entire artwork, but inevitably the altarpiece as a whole is discussed in Chapter 7, “Imagining the original display,” by Bart Fransen and Jean-Albert Glatigny. I wonder whether some of the information in this book will need to be repeated in future volumes that discuss the interior panels. Given the in-depth research contained in this volume, one expects that further research will help clarify – rather than correct – the findings presented here about the outside of the altarpiece.

Abbie Vandivere

Mauritshuis / University of Amsterdam