The massive polyptych known as The Ghent Altarpiece (Ghent, Cathedral of Saint Bavo) is one of the key monuments in the history of art. Originally comprised of twelve panels including nineteen paintings, the quatrain on the frame gives a date of 1432 and states that it was begun by Hubert van Eyck and finished by his brother Jan. Of Hubert almost nothing is known save that he died in 1426. On the other hand, Jan van Eyck (ca. 1390-1441) is a figure of singular importance. At the core of his oeuvre are nine signed and dated paintings made between 1432 and 1439. He was primarily a court artist, beloved and protected by Duke Philip the Good, and one for whom we have a certain amount of biographical information. It is no exaggeration to say that he is one of the greatest artists of all time and recognized as such since the fifteenth century.

The conservation of the Ghent Altarpiece began in 2012. The initial campaign, which ended in 2016, was restricted to the exterior panels. For the results of this investigation and treatment, see The Ghent Altarpiece: Research and Conservation of the Exterior (Contributions to the Study of the Flemish Primitives, 14), edited by Bart Fransen and Cyriel Stroo (Brussels: KIK-IRPA, 2020; reviewed by Abbie Vandivere for HNAR in October 2020).

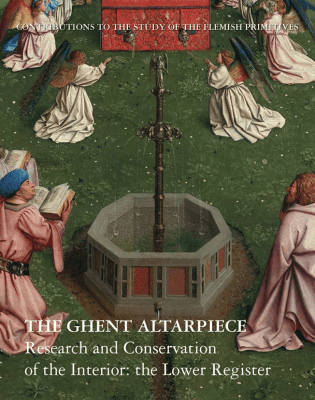

The volume under present consideration deals with the paintings on the interior of the lower register: Knights of Christ; Adoration of the Lamb; Hermits; and Pilgrims. As is well known, the Just Judges panel is a modern copy. In addition to this publication the authors also recommend consulting the excellent images on the Closer to Van Eyck website.

The first chapter discusses the conservation and restoration of the lower interior panels which took place between 2016 and 2019. This included the removal not only of multiple layers of varnish and retouching, but also sixteenth-century overpainting. These overpainted areas were followed by Michiel Coxcie in his copy of the Ghent Altarpiece done in 1557-1558 (the dismantled panels of which are now in Berlin, Munich, and Brussels).

The second chapter sets forth an analysis of the various stages in the creation of the altarpiece and in so doing confirms the inscription on the quatrain. The altarpiece was produced in three stages. Painted over a preparatory layer of chalk and animal glue, the first was a preliminary version of the composition, but several elements were abandoned or modified along the way. Unpainted borders and barbs tell us that the panels were already in their frames. The second phase is marked by a number of changes. In the center panel a fountain was added over a spring and a second meadow covered the first. The lamb was added and then enlarged over the background meadow, as technical photographs make clear. On the horizon buildings were added, including the tower of Utrecht Cathedral and the former Abbey of St. Bavo in Ghent (demolished in 1540). The authors attribute the first phase to Hubert van Eyck and the second phase to his brother Jan. Lastly, a third phase is identified which can be distinguished by the use of ultramarine rather than the azurite found in the other two layers. By virtue of their ineptness these paint strokes are believed to be later than the Van Eycks’. This is particularly true in the case of the dove who hovers at the top of the center panel.

The third chapter is an extensive report on the chemical analyses of the preparatory ground, priming, underdrawing, and paint layers. There is a useful chart (p. 119) and discussion of the pigments and additives that were disclosed. For the most part these correspond to the materials found in other Netherlandish paintings of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.

In the fourth and final chapter Griet Steyaert and Marie Postec use the conservation and restoration information as the basis for a stylistic analysis. At the risk of repeating what was said earlier, they conclude that the first stage was executed by Hubert van Eyck and in a second stage, Jan van Eyck finished the composition. In the case of the figures grouped around the Adoration of the Lamb in the center panel, some heads are assigned to Hubert, some to Jan, while a few others are considered to be by Hubert but reworked by Jan. Further, the “disordered impression” created by the underdrawing in the Adoration of the Lamb is alien to Jan’s more coherent manner and thus belongs to Hubert. Although I have not had the opportunity to examine the interior panels of the Ghent Altarpiece at first hand, I tend to agree with the differentiation and attributions to Hubert and Jan proposed by Steyaert and Postec. In the case of Hubert in particular this seems an excellent starting point for considering the attribution of other works to him. Keep in mind, however, that caution is required in attempting to distinguish the contributions of Hubert and Jan.

In sum, this generously illustrated, clearly written volume is an essential addition to the literature on the Ghent Altarpiece. Removing the dirt, varnish, and centuries of repaint has now allowed access to the staggering achievement of the Van Eycks and perhaps of equal importance, has provided a starting point for considering the oeuvre of Hubert van Eyck.

John Oliver Hand

National Gallery of Art Curator Emeritus