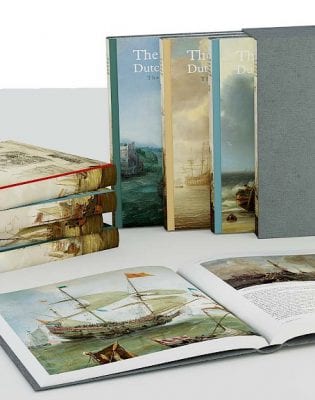

This lavishly produced four-volume boxed set accompanied an exhibition in 2019 at the Bredius Museum in The Hague devoted to the collection of Dutch marine paintings assembled by the London collector Anthony Inder Rieden. In the preface to this publication Inder Rieden comments that he did not collect over a forty-year period with the goal of assembling a comprehensive survey of Dutch seascape, but explicitly describes it as the result of his personal tastes and interests, guided by a focus on quality and condition. In consequence, the collection of sixty-seven paintings is in some respects idiosyncratic, with an emphasis on a number of less familiar seascape painters such as Cornelis Verbeeck, Justus de Verwer, Hans Goderis, Pieter Mulier, Hendrick Jacobsz. Dubbels, and Jan Abrahamsz. Beerstraten. The achievements of these “minor” masters are revealed in the numerous high-resolution details reproduced in the catalogue, in addition to many full-page details sprinkled through these volumes. Famous marine painters too are featured – Hendrick Vroom, Jan Porcellis, Simon de Vlieger, and Willem van de Velde the Younger, among others – but their works are seen in the collection and the catalogue in a wider context of images of quality and interest by artists of lesser fame. Another result of Inder Rieden’s personal interests are themes that receive more attention, most notably the number of beach and shore scenes, while other aspects of Dutch marine painting, especially large-scale works depicting battles and commemorating ceremonial occasions, typically made to public and private commission, are mostly absent.

The lead author of the catalogue, Gerlinde de Beer, is an authority on Dutch seascape, and the author of a monograph on the unjustly neglected master Ludolf Bakhuizen. In her introductory essay to the catalogue, de Beer laments the “dramatic lack of monographic studies” of Dutch marine painting, especially of catalogues raisonnés. She also comments on the number of flawed attributions she finds in such studies as there are, even while acknowledging the contributions of major scholars of this subject including, among others, Laurens J. Bol, George Keyes, Jeroen Giltaij, and the late Jan Kelch, a Simon de Vlieger specialist, to whom the publication is dedicated. Her catalogue of the Inder Rieden collection is clearly intended to be, at least in part, a contribution to remedying the state of research. Because the collection itself is so selective, volume one includes an overview essay by de Beer putting the collection into the larger development of Dutch marine art, surveying the state of scholarship on artists in roughly chronological order.

In this essay de Beer highlights in particular the contributions of Hendrick Cornelisz. Vroom, whom she rightly sees as the innovative source of many of the most important and long-lasting subjects and compositional types in Dutch marine painting and a major figure in the development of city views as well. Vroom’s primacy in many aspects of marine art seems secure, but the absence of dated paintings in the 1580s and 1590s means that some aspects of the development of this genre remain clouded. In this context de Beer’s disdain for the early marine specialist Cornelis Claesz. van Wieringen is particularly puzzling. Also surprising is her somewhat off-hand treatment of Jan van de Cappelle. While Van de Cappelle may not be adept at depicting ships sailing in stormy seas, his calm harbor scenes are masterpieces of value painting and of shimmering reflections illuminating remarkable, almost abstract compositions of sails, masts, spars, and rigging.

The publication contains an unusually substantial and illuminating catalogue of the paintings in the collection. Extensive entries by de Beer dedicated to each work include numerous comparable images by both the painters in question and related artists. They treat many features of the images such as vessel types, the implications of the sails and tactics of vessels, the activities of figures, the implications of costumes, and indications of topography. The author’s careful discussions of the compositional structures and light and atmospheric effects are remarkable. The result is something like a concise monograph for each artist, particularly those with more than one picture in the collection. In the first volume alone, the discussions of Jan Porcellis, Hans Goderis, and Simon de Vlieger stand out, as does the treatment of Andries van Eertvelt, the only artist primarily active in the Spanish Netherlands in the collection or treated at length in the catalogue. Jaap van der Veen’s often lengthy artist biographies, most of which incorporate original research, add substantially to the usefulness of the publication.

These volumes are illustrated with over 900 images, the vast majority reproduced in color, many for the first time. The reproductions are mostly of high quality; and, in addition to the large, sharp details of the Inder Rieden pictures, a number of details of comparative works are provided as well. A further feature enhancing the value of this compilation for research is that many of the comparative images, having appeared on the market in recent decades, are now in private hands, location unknown.

Another feature of the first volume of this work is the essay by the meteorologist Franz Ossing discussing the accuracy of the clouds depicted in Dutch marine images. Ossing uses the definitions of clouds and associated weather of the World Meteorological Organization and provides photographs of weather that he compares with specific Dutch paintings. He introduces two useful distinctions based on these comparisons: first, that earlier Dutch marine paintings depict generic clouds of varying degrees of puffiness or wispiness, while later artists, from the 1630s onward, are more accurate in rendering observable cloud formations; and second that even in the later period, pictures illustrating battles or ceremonial events have inaccurate clouds, while paintings depicting more daily-life kinds of scenes are much more true to natural appearances in depicting weather. The comparisons he draws are to varying degrees convincing, and his thesis that cloud formations in later, everyday life seascapes are much closer to clouds in nature seems to be largely true. The contention of John Walsh in 1991, however, that the Dutch depicted a selective range of weather phenomena remains substantially valid not least in that these artists did not depict the decidedly flat, often dark, bottoms of clouds. This is readily evident when comparing Ossing’s Figures 10 and 11, 14 and 15, 21 and 22, or 24 and 25, which often render specifically identifiable cloud structures but lack this feature. The accuracy of weather in Dutch marine painting is variable and selective, in that regard resembling the degree of accuracy seen in Dutch pictures of naval battles and other historical events – and in most other categories of Dutch Golden Age painting.

The value of this great compilation and analysis of information, old and new, and of numerous images providing a context for Inder Rieden’s pictures is compromised to some degree by the dispersal of data and images through the text. The tendency to separate the treatment of pictures by one artist with catalogue entries on paintings by other artists has something of a fragmenting effect on the presentation. This is especially the case in Volume I, but is evident in Volume II as well. This organizational decision amplifies another feature of the catalogue, which is the dispersal of works by influential artists like Jan Porcellis or Simon de Vlieger or Ludolf Bakhuizen through numerous catalogue entries. This makes it difficult to form a coherent image of artists’ production, though this may well be an unavoidable difficulty in an exhibition catalogue providing comparable images illustrating the influence of major artists’ innovations. This difficulty is to some degree mitigated by the extensive set of indices in volume IV, compiled along with the bibliography by Charles Dumas. These include indices of artists’ names, geographical names, ship names, historical events, image titles, and sales.

In considering the clear value of this publication for research, as well as for making an impressive collection available to a wider public, the question inevitably arises in this digital age whether this remarkable and beautifully produced print edition is actually the most effective way of publishing both the pictures and the results of the authors’ extensive research. Would a digital publication reach a vastly wider public and make the collection and the research on it more readily accessible? I imagine the answer to this question is yes. And yet, as anyone who has worked through the boxes of mounted photographs in the RKD in The Hague can attest, paper texts and photographs provide in their physical textures, visual properties, and even smells a satisfying sensory experience entirely lacking in digital publications. Weighing these qualities against the ease of access that digital images and information provide makes the conundrum clear. This set powerfully argues for the sensory satisfactions of more traditional forms of publication, even as it suggests their limitations.

Lawrence O. Goedde

University of Virginia