Our enduring attraction to Rembrandt and the vast art historical scholarship devoted to his works can be largely attributed to the artist’s boundless visual curiosity about everything he saw around him, or imagined, and his technical brilliance as a painter, draughtsman, and printmaker. A new book by Christopher White – his third on Rembrandt – encompasses all this and more with a compelling topic. The Intimate Rembrandt is about the artist’s distinctively introspective creative process and his constant attention, in and beyond depictions of people, to “life beneath the outer skin” (63). This deeper aspect of Rembrandt’s art has long been recognized, especially in his many self-portraits. Here, however, examples of both paintings and works on paper cover his full range of subject matter, over the trajectory of a long career within the context of his life and his responses to other artists. Five well-chosen chapters open with “The Artist and his Family,” followed by “Portraits in Situ,” “Everyday Life in Amsterdam,” “Landscape and the Bucolic Scene in the Countryside,” and finally, “Narrative Subjects.”

These essays are written with such clarity, personal warmth, and seemingly effortless mastery that a comment about the art historian himself seems appropriate here. Christopher White (knighted Sir Christopher in 2001 by the Queen whose collections of Dutch and Flemish pictures he catalogued) has had a distinguished career in British and American museums and universities, including his first appointment in 1954 as Assistant Keeper in the British Museum’s Department of Prints and Drawings and the directorship of the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford (1985 -1997). His extensive experience with major collections and his knowledge of works on paper give this volume its solid foundation, but it is the writer’s ability to capture so directly what he sees and feels that creates its exceptional appeal. That it was conceived with a general audience in mind is noted in the preface, but White’s professional colleagues will find much to inform and delight them, for his selections are often fresh and unexpected and even well-known works offer new insights.

The subtle shadings of effect and meaning that Christopher White notices often opened the eyes of this reader. Diverse examples of one small detail follow, for they highlight an easily overlooked motif: the hand. The early painting of Tobit and Anna of 1626 (139-142), which the author presents as the beginning of Rembrandt’s psychological approach to narrative, is a case in point. The work’s untraditional focus on Tobit lets the viewer experience his mortified repentance, conveyed by his hands as much as his face. In the tender silverpoint betrothal portrait of 1633 (11-12) Saskia’s “elegantly tapered” left hand, which draws attention to her eyes, normally goes unnoticed as we focus on the right hand holding the rose. In the etched Portrait of Ephraim Bonus of 1647 (56-58) the sitter gazes out in a contemplative moment, captured between his world and ours as his hand at the end of the banister places him exactly at the transition between the two. Most movingly, the intimate connection between an artist and his art is expressed in The Goldsmith etching of 1655 (104-105) where the big hand of the sculptor, embracing his statue, is echoed in the thin, delicate fingers of the sculpted Caritas figure embracing her child.

The author’s interest in Rembrandt’s depictions of hands parallels his close attention to the artist’s handling of his materials and implements. Etchings and pen-and-ink or chalk sketches of children (77-86) and animals (89-97) come wonderfully to life on the page, transfixing a reader seeing them through Christopher White’s eyes. In his later paintings Rembrandt’s daringly visible manipulation of oil paint produced works of arresting immediacy. Here White features the 1654 Portrait of Jan Six (62-64), in which the innovation of showing a man actively pulling on gloves is captured by both his pose and the thickly active brushwork. Not surprisingly, the “infinite subtlety of both subject and technique” in Hendrickje Wading (31-33), painted in the same year, emerges as the author’s special favorite. The book concludes with perhaps the most intimate and universally loved Rembrandt painting: The Jewish Bride of c.1665 (189-192). Rendered in the tangible, varied textures of thick brushwork, with flatter accents of the palette knife, this “marvel of painting” makes the embracing hands of Isaac and Rebecca its central focus.

A chapter devoted to landscape in a book about intimacy might seem misplaced until we recall Rembrandt’s erotic images, following Saskia’s death in 1642. In them amorous figures are fused within nature as in The Flute Player of the same year and The Sleeping Herdsman of 1645 (119-122). Less explicit, but deeply personal too, are his responses to his own local countryside outside Amsterdam, through which he walked again and again between 1640 and 1652, sketching trees, land, water and weathered cottages and farmhouses. Among the architectural examples are structures artfully cropped and modeled by light and shadow to bring out their complex shapes (109-112). Of the many splendid landscapes in this chapter, one of White’s choices stands out among Rembrandt’s most intimate studies of nature. This stunning black chalk drawing, Canal Between Bushes in the National Institute, Wroclaw, of c.1645 (116-117) takes us into a private corner of nature where soft foliage and watery reflections, framed by tall trees and a wooden footbridge, place the viewer directly within its shimmering world.

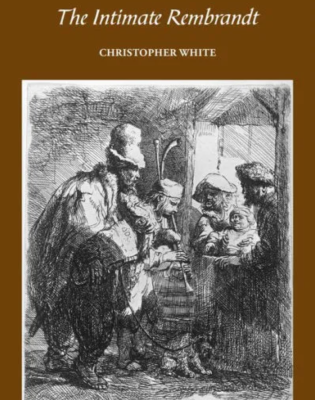

Rembrandt’s repeated explorations of human encounters, we find, ranged from serious historical narratives to the most down-to-earth incidents of everyday life. Surely the oddest in this volume is The Rat Catcher etching of 1632 (75-77). As White points out, its disjunction between the householder inside the open door and the itinerant outsiders is utterly unlike the harmoniously unified grouping in a later print of 1648, where a blind street musician and his family receive alms at a similar doorway (98-100).The author credits the contrast to Rembrandt’s maturing approach to composition, but this reader also noticed how well this example sharpens the book’s focus on intimacy by showing its opposite.Instead of Christian charity to beggars, the transaction for rat poison involves an awkward confrontation between social opposites. The grisly presence of the seller, with his display of dead and living rodents atop a tall vertical pole, is only slightly mitigated by the pet rat on his shoulder. As the client recoils in disgust, the men’s hands barely touch just outside the threshold as both the doorway and the composition isolate each one within this intimate glimpse of urban alienation.

For both author and publisher, the challenge of producing this book must have been considerable. There were so many choices to make, or regretfully decline, to cover such diverse material under the umbrella of “intimacy.” The result is a volume, easily held in the hand, which calls for close attention but remains invitingly accessible. The many small but excellent color reproductions are so well placed that a reader can examine each one almost side by side with the author’s words. This is not a study to scan quickly, but to savor slowly. That, after all, is the condition for every kind of intimacy: the opportunity and time to feel closely connected, within one’s individual self, to a person, a place, an idea, an artist, or a work of art. Here we find them all within Rembrandt’s presence and Sir Christopher’s too.

Susan Donahue Kuretsky

Professor of Art Emerita

Vassar College