In September of 2020, the Royal Library of Belgium in Brussels opened a state-of-the-art museum to great fanfare. Its purpose is to offer the public the opportunity to enjoy a rotating exhibit of medieval manuscripts from the collection. (Longtime users of the Royal Library will also be pleased to learn that the fifth-floor cafeteria, previously open only to library staff, will also shortly open to the public as a full-fledged restaurant.) The core of the Royal Library’s late medieval holdings, of course, are the hundreds of manuscripts, many richly illustrated by the leading artists of their day, that were commissioned or acquired by four successive dukes of Burgundy: Philip the Bold (reigned 1363–1404), John the Fearless (1404–19), Philip the Good (1419–67), and Charles the Bold (1467–77). Among these codices, the richest trove in the Royal Library are the almost 300 volumes cited in the post-mortem inventory of Philip the Good’s manuscripts.

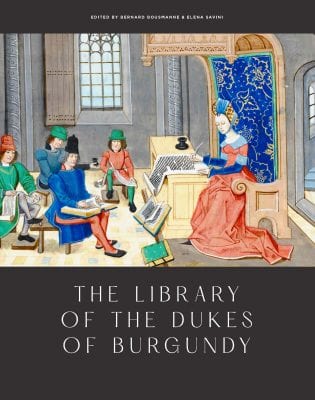

To celebrate the opening of the Royal Library Museum, head curator Bernard Bousmanne and co-curator Elena Savini have edited a beautifully designed and richly illustrated volume of essays with contributions by the two curators and eight other late medieval specialists entitled The Library of the Dukes of Burgundy. As the absence of footnotes or endnotes makes clear, the publication’s primary target audience is the educated general reader rather than scholarly specialists. A one-page Preface by Royal Library director Sara Lammens is followed by five essays complemented by 63 figures. In the first, Bernard Bousmanne provides a history of the ducal library from its inception in the late fourteenth century to the establishment of the kingdom of Belgium in the early nineteenth century. The second, by art historian Dominique Vanwijnsberghe, provides an overview of southern Netherlandish illumination from Philip the Bold to Charles the Bold. In the third, historian Jelle Haemers looks at the roles of consent and confrontation in the Low Countries across the entirety of the late medieval Burgundian era (1384–1506). The fourth essay, by literary specialists Tania Van Hemelryck and Olivier Delsaux, considers French literature at the Burgundian ducal court from Philip the Bold to Charles the Bold. In the fifth, Royal Library conservator Tatiana Gersten describes the work of restoring and caring for its manuscript holdings. The book concludes with a catalogue of 55 Burgundian manuscripts in the Royal Library. Each codex is accompanied by a descriptive text; the 83 color illustrations in this final section ensure that at least one page from each of the 55 books is reproduced.

At the incipit of his contribution, Vanwijnsberghe notes that his text is based on his scholarly essay in volume V of La Librairie des ducs de Bourgogne: Manuscrits conservés à la Bibliothèque royale de Belgique (Brussels, 2015). His 2015 essay is complemented by 23 color figures, eight of which are also found among the 13 figures in the 2020 essay. Setting the two essays side by side thus provides readers with 28 figures. Another 23 manuscripts considered in the 2020 essay are the subjects of individual catalogue entries at the end of the volume. Unfortunately, readers cannot readily turn to that bounty of additional images and accompanying texts, the latter of which offer the interpretative perspectives of other contributors, because the codices in the 2020 catalogue are not numbered; are not in shelf-number or chronological order within that catalogue; and are not indexed in an alphabetical list of manuscripts cited, reproduced, or both. As a consequence, Vanwijnsberghe can only cite the Royal Library shelf numbers in his contribution, forcing readers to create their own indices if they are to locate the 23 manuscripts and accompanying texts in the catalogue and thereby draw the fullest benefit from their reading of Vanwijnsberghe’s essay. The other essay to suffer from this absence of indexing is the study by Tania Van Hemelryck and Olivier Delsaux. Fully 30 of the manuscripts cited by the authors are illustrated in the catalogue of manuscripts, and 28 of the 30 accompanying texts are by other contributors. But like Vanwijnsberghe, Van Hemelryck and Delsaux were only able to cite the Royal Library shelf numbers within their essay.

Fortunately, these shortcomings do not compromise the three other essays in The Library of the Dukes of Burgundy: Bousmanne, Haemers, and Gersten cite no Royal Library manuscripts beyond those that they illustrate within their texts. Of the three, the contribution of Haemers is the most ambitious. A late medieval urban historian, he is a member of the Young Academy of Belgium, an “association of young top researchers and artists with their own views on policy, society, research, and the arts” (kvab.be/en/young-academy). Haemers informs us from the start that he will not view the history of the late medieval Burgundian Netherlands only through the traditional lenses of the dukes themselves, the ducal court, the nobility, elite churchmen, and the urban patriciate, all of them overwhelmingly men. Instead, he will give equal attention to rich and poor, powerful and powerless, rural and urban, secular and religious, and female and male in order to elucidate how all of the social estates actively or passively worked in the political, economic, social, and cultural arenas to check and balance one another’s power and personal interests.

Haemers bookends his narrative with two events that transpired near the beginning and the end of the Burgundian era in Sluis, some 16 kilometers northeast of Bruges. The first, in 1396, involved a woman named Wendelkin, otherwise unknown but probably of modest social station, who was made to march through the streets of Sluis weighted with two heavy stones while declaring loudly in each street that she had spread rumors about the previous Count of Flanders, Louis de Mâle, and had sung ditties that ridiculed him. Haemers provides an illustration of a punishment like Wendelkin’s in a bas-de-page in the celebrated Hours of Catherine of Cleves (fig. 28). The second event, in 1492, involved two powerful men: on 12 October of that year the armistice known as the Peace of Sluis was signed by the nobleman Philip of Cleves, lord of Ravenstein (1459–1528), and his suzerain, the Holy Roman emperor Maximilian I (1459–1519). Philip had turned Sluis into a stronghold of resistance to Maximilian rather than acknowledge the emperor as the rightful regent of his 14-year-old son by Mary of Burgundy, Philip the Handsome (1478–1506). What was at stake was the delicate balance of power between the emperor and the Burgundian nobility. When Maximilian could not dislodge Philip from Sluis militarily, the former accused the latter of slander, rebellion, and treason, just as Wendelken had been accused of slandering Louis de Mâle a century before. Those two happenings in Sluis and the succession of Burgundian historical events and personalities in between them are brought to life by Haemers with perspicuity and verve.

Its structural shortcomings aside, The Library of the Dukes of Burgundy is a welcome addition to the secondary literature on the late medieval Burgundian Netherlands, and will provide pleasure and benefit to readers interested in the era’s history, literature, and art history as well as the science of book conservation.

Gregory Clark

Sewanee: The University of the South