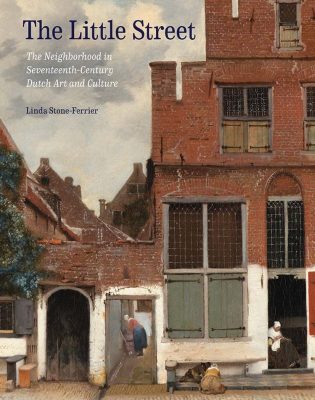

Vermeer’s so-called “Little Street”, which gives this striking book its name and graces its cover, depicts fragments of two housefronts linked by adjoining courtyards. Rooftops cluster in the distance. Two women, each at a different task, and a pair of children playing together, appear as if from across the street. They are too far away for their faces to be seen clearly, but close enough to look up if we called out to them. In other words, this serene moment represents a momentary view of a neighborhood.

Linda Stone-Ferrier shows how these local communities had great significance in Dutch urban culture. Her study of neighborhood as a subject for art – essentially hiding in plain sight – includes many engaging pictures, some rarely reproduced, others well known and seen afresh like Vermeer’s. The scrutiny she give these images feels long overdue. Along with the main dramas of community life, small details such as backgrounds, far-off figures, shop-signs, bridges, graffiti and more, often overlooked in earlier studies, get careful attention. The results are revelatory.

What exactly was a neighborhood? A block or two of houses, or a stretch of canal. The great influx of immigrants to Dutch cities in the first part of the seventeenth century created a dense, diverse population. Apart from larger municipal divisions of cities for taxes and services, neighborhood organizations (gebuyrten) were self-organized, operating freely and without supervision, electing their own leaders, and establishing their own regulations, to uphold ideals of togetherness. Unlike other organizations and institutions (such as guilds, confraternities, and so on) the communities were open to all, regardless of social status, religion, citizenship, or gender. They had names, identities, and reputations, “provid[ing] a primary organizing unit and social control in daily life.” (165)

Not surprisingly, there developed a market for images celebrating these gebuyrten and their shared values. The pictures realize an ideal beyond the messy realities of urban life. Neighbors mingle with conviviality and ease. The weather is always sunny, the streets are clean and tidy, and the ambience is calm. Stone-Ferrier distinguishes these scenes from more anonymous, commemorative city views evoking generalized civic or national pride. She observes that in inventories and auction records, pictures were described not as “city views” but as “neighborhood,” “street,” “canal,” “house“, “some houses,” and so on.

This book also sets out a distinct art-historical path. Rather than studying a single subject or genre, Stone-Ferrier proposes that not only street scenes, but portraits, images of household or courtship activity, stores and workshops, celebrations and festivals all “share the neighborhood as a meaningful context.” Further, she reconsiders the by now standard private – versus public – social analysis of Dutch pictures, with its attendant gender identification. Instead of seeing in Dutch interiors a link between home and world, she casts the neighborhood itself as an experience and a setting, which “served as the liminal bridge between home and city.” (3) She suggests that further pictures beyond this book might benefit from study through the lens of neighborhood culture.

Stone-Ferrier draws on scholarship in social history, sociology, anthropology, gender studies, to show how Dutch pictures reveal the interdependence of social relations in a small yet vibrant urban area. Along with stage designs, architectural books, city maps and plans, other primary sources such as inventories and auction lists, municipal records, city descriptions, letters, and diaries present some of what neighborhood life was like and what went into its representation. In an especially rich passage, Stone-Ferrier suggests how pictures (her example is a street scene by Jacob Vrel) might suggest not just the sights of a community’s daily life, but its soundscape: …“the cries of a street vendor, a bucket clanging in a well, [and] the squeaking of the shop signs buffeted by the wind …, the click-clack of steps on a tile or stone stoop …”(21) The audience for such pictures, perhaps residents of the community, perhaps from elsewhere, could orient themselves to a specific place.

This interpretive focus encompasses a range of engaging scenes. Views by Jan van der Heyden and Gerrit Berckheyde of canals and squares, often clearly identifiable, capture quotidian detail and even particular times of day. House interiors and courtyards by Pieter De Hooch and Ludolf de Jonghe are punctuated with neighbors who enter, peer inside, or are glimpsed across a street or canal. Jacob Ochtervelt, Gabriel Metsu and Nicolaes Maes depict people at their doorways, interacting with other locals: messengers, fruit sellers, street musicians, seekers of charity. This imagery of the immediate community was exclusive to the Dutch. Stone-Ferrier points out that while other early modern cities had similar small communities (Ghent, London and Paris, for example), they lacked the “native pictorial traditions that could have fostered neighborhood-related subject matter.” (2)

Introducing this uniquely Dutch imagery, the first two chapters are devoted to the cities of Delft, Amsterdam, and Haarlem. Stone-Ferrier offers a few examples of pictures of depicted areas in each city, sometimes interactions between two people, sometimes street scenes. Almost all are recognizable areas, sometimes with reshuffling of details, like Vermeer’s. One spot-on feature: we learn not only which street the artist lived on, but how long it would take him to walk to the location he depicts.

During the 1650s, Delft artists such as Jacob Vrel and Jan van Der Heyden began producing small-scale street scenes, responding to a rising market for images of local customs. At the same time, they were incorporating perspective design into their work, a practice which spread beyond Delft to other cities. Stone-Ferrier situates such pictures of community life in a larger visual culture of portraying streets with buildings: architectural designs of Hans Vredeman de Vries; the elegant rows of houses in Sebastiano Serlio’s theater designs; and the influence of both on set designs for the Amsterdam theater. She frames Carel Fabritius’s View of Delft with a Music Stall as not just as a performance in optics and perspective, but as a neighborhood scene. She further shows how Jan Steen sets a portrait in a local context, depicting his neighbor Adolf Croeser at the front stoop of his house.

In Haarlem, Job and Gerrit Berckheyde experimented with oblique views of the large marketplace next to St. Bavo’s Cathedral, from the perspective of locals walking through it. In Amsterdam there developed a market demand for scenes of new neighborhoods, and more elegant ones. Van der Heyden, having left Delft, may have been inspired by the rebuilding of the Town Hall in 1660 to create images of the Dam Square from several viewpoints. He also produced scenes of various neighborhoods, sometimes under construction.

The three chapters that follow are thematic, exploring characters, experiences, and rituals of neighborhood life. The first of these chapters, appealingly subtitled “Glimpses, Glances, and Gossip,” describes how community life involved seeing and being seen, and how this appears in pictures. Residents “intervened in each other’s lives to negotiate conflicts…” since it was for the communal good. Neighborhood honor would depend on mutual visibility and support. Typically, this is depicted only in a positive or perhaps comic manner, omitting any actual tensions. Scenes of houses and courtyards reveal people sitting at windows and doorways, looking out while others look in. A sub-genre of the half-length figure looking directly at the viewer through a window or half door is interpreted here as a moment of personal engagement, a common encounter in neighborhood life. (Rembrandt’s Girl at a Window is an interesting example here.)

Stone-Ferrier also shows how architectural design enabled people to see each other easily. The ideal house design recommended by Flemish architect and engineer Simon Stevin – voorhuis, achterhuis, courtyard – was concretely realized in community experience. Many interior scenes are situated at or near the voorhuis, the liminal space right off the street which “functioned as a private display for public scrutiny.” (92 Details of construction also contributed to such scrutiny. In Maes’s Virtuous Woman, a woman sits sewing at a window as a child pulls on the shutter and looks in. Her chair rests on a zoldertje, a wooden platform which enabled people to see outside the window to the street. Zoldertjes of different sizes were typical features of house and shop interiors, frequently represented in pictures.

The next chapter turns to images of local trades and artisans. Artisans, like shoemakers, tailors, smiths and bakers, were depicted frequently, along with alchemists, pharmacists and barber/surgeons. The display of wares and depiction of commerce reinforced the status of local tradespeople whose clients were their own neighbors. Along with indoor scenes of shops, showing artisans at work with their patrons looking on, other scenes are set in a framing window, with sculpture relief on the outside. Stone-Ferrier shows how these nisstukken and their reliefs are not necessarily motifs about illusionistic painting but actual architectural details on houses. These were essentially advertisements, and their compositions were also used for signs and commemorative medals for guilds. Images of painters in their studios – also forms of self-promotion – are offered as the exception. While artists might live in the same neighborhood as their patrons, their businesses were not necessarily tied there. These images are more generic, omitting local details.

The author proposes an intriguing reason why many trades were never pictured in Dutch art, such as cabinetmaking, construction, the grain trade, dairy, harbor work, fishing and shipbuilding industries. These industries contributed to civic well-being and the Dutch economy as a whole, rather than to a particular neighborhood. Their activities “took place in a centralized location within a city, at an ever-changing civic site, or on a city’s outskirts” (130). Such was the neighborhood orientation of urban imagery.

The final chapter, “Neighborhood fraternity,” explores pictures of events which embraced the whole community. Life-cycle events – births, marriages, funerals – involved the presence of neighbors, not only members of a single household. Metsu’s Visit to the Nursery depicts a popular “lying-in” ritual, where newborn babies were shown to local visitors. Weddings, deathbed scenes, and funeral processions, such as depicted in Emanuel de Witte’s Interior of the Oude Kerk, Amsterdam likewise involved the whole community.

Finally, pictures of merrymaking by Jan Steen are reinterpreted as depictions of annual feasts as well as holiday celebrations. Such events, described in city documents, were regular features of neighborhood life. Steen’s revelers in these crowded, vivacious scenes reflect a wide range of ages and professions, clothing, and behavior, like the inhabitants of street scenes. Some can even be identified as elected neighborhood officials. Like the smaller-scale images examined throughout this study, these scenes of festive diversity would enhance and reinforce a community’s sense of shared values. In an afterword, Stone-Ferrier describes sociological approaches to urban life and how these community ideals – ties of honor and reputation, mutual respect and aid – persist to this day.

This lucidly written book sparkles with insights, unexpected associations, and rigorous scholarship. (I should point out that the great variety of sources is difficult to pin down since there is no bibliography – incomprehensible in a scholarly work.) Two ideas emerge. One is the strong presence and agency of women. They are everywhere in scenes of community life, at a distance and up close. In courtyards, houses, streets, women are observing, buying and selling, socializing – sometimes with men, a practice documented despite moralizing texts. Second is the market for pictures that engage audiences with a sense of belonging, in particular to a physical location. It attests to the enormous psychological power of seventeenth-century Dutch imagery in the daily lives of its viewers.

Martha Hollander

Hofstra University, emerita