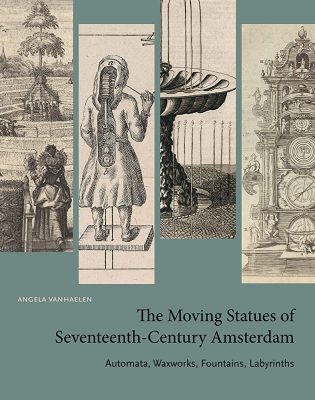

Among the cultural developments in seventeenth-century Amsterdam, the city’s doolhoven – planned environments containing moving sculptures, fountains, automata, waxworks, and clockworks – have remained among the most obscure. After receiving a smattering of scholarly attention beginning in the 1960s, these labyrinthine displays had been in more recent times overlooked by historians and art historians.[1] The situation began to reverse in 2004 when Angela Vanhaelen published an important article that situated the doolhoven in the context of Amsterdam’s religious culture and urbanism.[2] The book under review, a significant expansion upon the author’s previous work, examines the doolhoven afresh with thoughtful, detailed clarity. It enables readers to picture an important aspect of Amsterdam’s visual culture far more clearly than previously possible.

Vanhaelen provides a thorough theoretical framing of the topic in her opening chapter She begins with a drawing by antiquarian and accomplished draftsman J. G. L. Rieke of the unremarkable entrance to Amsterdam’s Oude Doolhof, which was located on the city’s modern outskirts. In Vanhaelen’s vision, Rieke’s conspicuously “clumsy” technique presents the doorway in the rhopographic tradition; an “uninteresting exterior” conceals “something intricate, artful, and potentially wondrous” (7). Vanhaelen credits Svetlana Alpers’s Art of Describing with sparking the field’s recent visual cultural turn beyond a focus on great master paintings to assess previously marginalized productions such as the doolhof and Rieke’s pedestrian drawing. However, she distinguishes the doolhof’s gallery of “illusory tricks” (18) from the scientifically grounded, descriptive mimesis at the core of Alpers’s argument. Recent works by Caroline van Eck, Frederica Jacobs, and especially Thijs Weststeijn (Visible World), comprise important interpretive models for Moving Statues.[3] Vanhaelen cites their attentiveness to the “moving quality” (19) with which early modern Netherlandish artists strove to infuse their works, and which audiences were encouraged to see in them. For Vanhaelen, doolhoven offered “models for understanding seventeenth-century visual culture as experimental, affective, embodied, and performative” (19).

Vanhaelen sequences her subsequent chapters to bring us inside and through Amsterdam’s doolhoven. Along the way, she tracks reception to a broad range of doolhof features, linking them to various cultural productions and historical events and contextualizing doolhoven within their developing political and technological spheres, respectively, tracing the history of the form. The book’s first two chapters comprising Part 1, “Ritual Routes,” explores the Bacchic fountains gracing the courtyards of the Oude and Nieuwe Doolhoven and their labyrinths beyond. Vanhaelen points out the importance of libations for the reception of these spaces, adjacent as they were to taverns. None other than Karel van Mander, she reminds us, dedicated Het Schilder-Boeck to two tavern keepers who collected and displayed art. Vanhaelen finds in the Oude Doolhof’s proprietor, Vincent Jacobsz. Coster the very type of cultural actor Van Mander praised. “Bacchus was his god,” she states (38). Moreover, he was a “leading citizen and avid art lover” whose Doolhof exhibits qualify him for Vanhaelen’s laudatory descriptor, “innovative curator” (38). For Vanhaelen, the Oude Doolhof’s elaborate Triumph of Bacchus and Ariadne fountain signifies most exemplarily the way the doolhof’s sequence of viewing experiences heightens awareness. Emblematizing intoxication at the start of the journey, the fountain shot water up the skirts of women who dared come near to investigate. As such, the fountain operates “in the manner of discordia concors;”per Vanhaelen, “immoderate desires were aroused by the salacious [fountain] and then quenched” (48), thus preparing participants for the intellectual challenges that lay beyond, in the maze leading to the sculpture gallery. For Vanhaelen, the maze comprised a metaphor for navigating past life’s temptations and confusions to lead a pious life. Calvin himself, she points out, compared such temptations to “an inexplicable labyrinth” (57).

In Part 2, “The Moving Statue Strikes” Vanhaelen brings us into in the sculpture gallery itself. The author surmises that, “the sobering test of solving the maze was a rite of preparation to attain an appropriately receptive state” (77) in which to view the doolhof’s displays. Over two chapters, this part lays out types of works, their content, and how they functioned for viewers. Vanhaelen identifies three types of works in the gallery proper: figures, picture shows, and clockworks, all of which were kinetic and introduced by showmen. From the start, the author is intent on layering our understanding of these displays philosophically. She links their functions – “to amaze, confound, and change” (82) their audiences – to Aristotle’s musing that wonder prompted thoughts on the origins of things. Thus, for example, while images of the story of David and Goliath encouraged viewers to contemplate its meaning, its recreation via moving sculptures gives rise to questions about the relation between divine will and human agency. Part 2’s second chapter links the “transcultural” nature of many of the doolhof’s automata to Amsterdam’s diverse population and its status as an international trade hub. Vanhaelen cites Descartes’s notion that the “repeated encounters with strange things” constitutes the “cure for astonishment” (103). In this way, doolhoven functioned as early modern means for raising global consciousness.

Part 3, “Protestant Paganism,” focuses on the doolhof’s sculptures of kings and princes, seated behind the moving, mechanical shows, and, as its title suggests, the relation between these displays and the religious politics that informed their production and reception. Here, Vanhaelen asks if the Reform-inflected fear that sculptures in sacred environments risked idol worship was transferrable to these secular environments. By Part 3, she has primed us for her answer: a resounding “yes.” But how did such conflict play itself out in doolhoven? Vanhaelen declares that “the victory of Protestantism in Europe” was the doolhof’s “unifying purpose” (132). Thus, the exhibit’s mixture of beloved and infamous figures – particularly the Duke of Alba in the latter category – facilitated a shared memory of the atrocities the Spanish perpetrated on the Dutch. The Oude Doolhof’s statue of Alba, whom William of Orange, called “a Nebuchadnezzar,” appeared to viewers in an “idolatrous and vainglorious light,” thus spurring “critiques of monarchical authority” (144). This historical consciousness is important for understanding the significance of the doolof’s clockworks, which Vanhaelen describes in her final chapter. They reminded audiences of the temporality of the events portrayed, recent history’s status as a comparandum with the ancient past and a warning of the end of time. In her epilogue, Vanhaelen traces the doolhof’s decline to obsolescence in the nineteenth century.

Viewing engagement lies at the core of Vanhaelen’s interpretation of doolhoven Nevertheless, questions regarding reception arise. The author contends that the doolhoven “took mimesis to its extremes … deceiving the viewer” into believing that the sculptures therein were living beings (18). To be sure, some contemporary viewers did write about the trickiness of the moving sculptures; these passages are duly cited by the author. To stress repeatedly that viewers were deceived, however, seems to me an overplay. Noting that works of art looked “as if alive” was a frequently deployed rhetorical conceit, as often applied to two-dimensional productions that did not move And beyond the fountains that doused viewers with water, we find little evidence for other specific ways in which automata and their audiences interacted. It seems, in fact, that despite their more physical aspect, the main mode of reception that doolhoven engendered was spectatorial, even cerebral. The many sources Vanhaelen quotes attest to this as they ponder the philosophical implications in the perceived vivification of these non-living, albeit kinetic things. This book’s “elephant in the room,” then: rather than being “deceived” by automata, viewers knew full well that what they were looking at did not live. Accordingly, where the phrase “as if” precedes the words “they live,” it embeds a rich poetics. It seems more likely to me that viewers knowingly suspended their disbelief to explore mimesis’s treasure trove of metaphors. This slight overreach in no way clouds the author’s main point: that by virtue of their motion, automata made a more visceral appeal to their audiences, one that activated a broader range of senses, thus classifying them as a breed of image that prompts their own important set of questions.

This valuable book, written in an engaging storytelling mode that never sacrifices rigor, teaches us much that we did not know about Amsterdam’s doolhoven. Before its publication, those enriched, dynamic display environments were nearly lost to us. Now, thanks to Vanhaelen, we at last have a clear vision of them.

Arthur Di Furia

The Savannah College of Art and Design

______________________________________________________________

[1] Key works include Silvio Bedini, “The Role of Automata in the History of Technology,” Technology and Culture 5 no. 1 (1964): 24–42; Hanny Reneman, Het ‘Oude Doolhof’ te Amsterdam, PhD diss., Leiden University, 1975; Jean-Claude Beaune, “The Classical Age of Automata: An Impressionistic Survey from the Sixteenth to the Nineteenth Century,” in: Fragments for a History of the Human Body, Michel Feher et. al., eds., (New York: Zone Books, 1989): 431–80.

[2] Angela Vanhaelen, “Local Sites, Foreign Sights: A Sailor’s Sketchbook of Human and Animal Curiosities in Early Modern Amsterdam,” RES: Journal of Anthropology and Aesthetics 45 (Spring 2004): 256–72.

[3] Thijs Weststijn, The Visible World, Samuel van Hoogstraten’s Art Theory and the Legitimation of Painting in the Dutch Golden Age (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2008); Frederica Jacobs, The Living Image in Renaissance Art (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009); Caroline van Eck, Art, Agency, and Living Presence: from the Animated Image to the Obsessive Object (Leiden: De Gruyter, 2015).