Lynn Jacobs has long been fascinated by Netherlandish altarpieces. Her pioneering Early Netherlandish Carved Altarpieces, 1380-1550 (1998) explored the diverse forms, manufacture, and sale of often elaborate wooden altarpieces across Europe. Next came Opening Doors: The Early Netherlandish Triptych Reinterpreted (2012), in which Jacobs asked what role “the triptych format might have played in the construction of meaning” (p. 1). How do the different parts, such as the center versus its wings or the interior versus the exterior panels, relate as the triptych is opened and closed? How do the panels convey thresholds and boundaries? Jacobs extended her inquiry to include sculpture and manuscript illumination as well as painting in her wide-ranging book Thresholds and Boundaries: Liminality in Netherlandish Art (1385-1530) (2018).

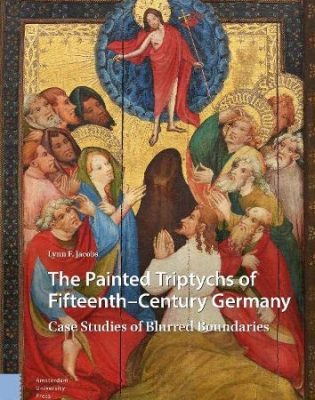

In her latest book, the author casts her discerning eye upon German painted triptychs. Here the blurred boundaries can refer to details of a specific triptych or to the permeable geographic and artistic borders between the Low Countries and the German lands. She challenges the long-standing assumptions that German painting was old-fashioned when compared with the Netherlandish ars nova. German masters were influenced by Netherlandish painting but often they intentionally held to their own traditions and aesthetic goals.

The introduction begins with a useful historiographic summary of the almost exclusively German-language literature. The field was shaped by Alfred Stange’s eleven-volume Deutsche Malerei der Gotik (1934-61) with its organization by regions, masters, and stylistic distinctions. Stange’s corpus has never had the same influence as Max J. Friedländer’s fourteen-volume Early Netherlandish Painting (1924-37; English translation 1967-76). Stange’s Nazi ideology has affected the reception of his series and long inhibited the study of the subject. Over the past three or four decades there has been a striking renewal of interest in German paintings, including Robert Suckale’s book on Franconian painting (2009), exhibitions on art in Cologne and other leading centers, monographs on single masters, and several superb museum collection catalogues. Jacobs adopts the German term Medialität that she defines as “the consequences arising out of a medium” (p. 30), including function, format, and medium-specific methodologies. The book focuses solely on painted triptychs rather than on the multitude of German altarpieces combining painting with sculpture. Jacobs restricts the scope of her book to a series of diverse case studies.

Chapter 1 (“Framed Boundaries”) opens with Conrad von Soest’s Niederwildungen Altarpiece (1403) in the Stadtkirche in Bad Wildungen. Like many Westphalian altarpieces, multiple small Infancy and Passion scenes are arranged across the interior. Clear pastiglia (decorative molded chalk) borders frame the individual narrative cells. Jacobs observes that von Soest subtly but quite intentionally breaches this seemingly rigid segmentation. He “transgresses” the borders by painting over some of the edges, such as the bright red cloak of the woman holding the turtledoves in The Presentation in the Temple. Did von Soest single out her as a mediating figure for the viewer, as Jacobs suggests? On the other hand, did he just need a bit more space better to include the bottom of her cloak? I wonder how legible this detail would have been to worshippers gazing from the front of the nave into the two-bay choir of this parish church. Other visual intrusions, notably Christ’s Ascension, breaching its upper frame and the lower edge of the scene of Christ in the Garden, are more visible at a distance. Was this painting-outside-the-lines a means of highlighting specific figures and details to generate meaning or a practice for displaying von Soest’s inventiveness? As Jacobs shows, von Soest’s followers borrowed this practice.

Chapter 2 (“Transparent Boundaries”) challenges the scholarly assumption that Netherlandish triptychs with grisaille exteriors and frequent fictive imitations of sculpture were the period’s standards. Most German artists, whether the Master of the Ehningen Altarpiece or Stefan Lochner, used similar color schemes and full pictorial scenes on the interior and exterior of their altarpieces. Jacobs argues that this scheme better harmonized the visual continuities, notably the liminality and “iconographic transparency” (p. 157), between the outside and inside of their triptychs. Particularly interesting is Jacobs’ discussion of Gabriel Angler, the Munich artist, who often employed various muted monochromatic tones throughout his altars, such as the Tabula Magna (1444-45).

Chapter 3 (“Regional Boundaries”) uses Rogier van der Weyden’s Columba Altarpiece (c. 1450-56; Munich), formerly in the Church of St. Columba in Cologne, as a case study for examining artistic choices and interchange. Did van der Weyden stop in Cologne while traveling on his pilgrimage to Rome in 1450? Jacobs suggests that the Netherlandish artist saw and was influenced by Lochner’s paintings, notably the Adoration of the Magi Altarpiece (or Dombild; 1442-45) painted for the city’s Ratskapelle in St. Maria in Jerusalem. The unknown patron, perhaps Johann I Rinck, may have stipulated the altarpiece’s large scale, which was more typical in Cologne than in Netherlandish triptychs, as well as its iconography, which celebrates the Three Kings, whose relics are in Cologne Cathedral. Yet other figural details, such as the woman dressed in green in Van der Weyden’s Presentation in the Temple, might derive from Lochner. Jacobs points out that while later Cologne artists were strongly influenced by Van der Weyden’s figures, they long adhered to local predilections, notable for gold leaf backgrounds and small-scale portrayal of donors.

Chapter 4 (“Spiritual Boundaries”) centers on the Master of St. Bartholomew. Scholars disagree about whether this artist was Dutch-born (?) and trained before moving to Cologne or whether his training and career were entirely in Cologne. Jakobs is interested in what she refers to as the boundaries between religious intensity and humor in his paintings. Are features like exaggerated poses, oddly shaped feet, foppish clothing, or two saints leaning on each other as if they were a couple expressions of ironic humor or else the artist’s striving for visual variety and emotional involvement in his paintings? The artist mimics polychromed and grisaille sculpture in several triptychs unlike most of the other contemporary Cologne masters.

Like her other books, Jacobs concludes with a coda of what happened next. In this case, how did the German painted triptych change in the age of Dürer? She addresses how Dürer, Hans Baldung Grien, and Lucas Cranach the Elder continued to exploit the triptych format, including the boundaries between the open and closed settings. Jacobs discusses how Cranach adapted the triptych to Lutheran altarpieces. Although outside the scope of her study, I wonder what insights she might have about the painted triptychs of a later master like Cologne’s Bartholomäus Bruyn, who studied with Jan Joest and Joos van Cleve.

Lynn Jacobs’s The Painted Triptych of Fifteenth-Century Germany is fascinating. Its grounding in close looking opens up surprising new insights as she guides you expertly through frequently overlooked details in these altarpieces. She also raises sometimes unanswerable questions about artists’ intentions and the contemporary reception of triptychs. Jacobs wisely limited the scope of her book to her chosen case studies. Yet I wonder how the story might change if she had investigated Franconian triptychs or those of Lübeck and Hamburg instead of Cologne’s triptychs. The richness and diversity of German fifteenth-century art, including the popularity of altarpieces combining painting with sculpture or wholly sculpted triptychs, offer other insights into Medialität.

Jeffrey Chipps Smith

University of Texas, Austin