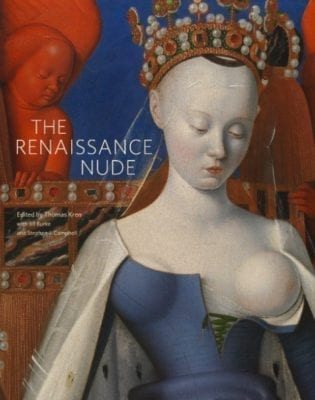

This handsomely produced and beautifully illustrated catalogue considers the development of the naturalistic nude in various media produced in northern and southern Europe, c. 1400-1530. It accompanied an exhibition originating at the J. Paul Getty Museum and shown in modified form at London’s Royal Academy. Today the nude is seen as a defining feature of Renaissance art. As this collection of eleven essays and 112 catalogue entries written by eighteen scholars clarifies, the nude as a subject for art arose in the early fifteenth century both in the North, when artists demonstrated increasing interest in the natural world, and in Italy, when others turned to classical sources to explore the human form. The essays, each followed by catalogue entries, consider themes including the roles of religion, the Reformation, and humanism; poetic traditions and the rise of secular art; artistic theory, beauty, and aesthetic pleasure; workshop practices, life drawings, and printmaking; eroticism and shame; and both ideal and dangerous female nudes, and heroic and abject male figures.

Jill Burke, Stephen J. Campbell, and Thomas Kren open with an overview (1400-1530) of major developments during this period and the many conflicting responses to nude imagery, whether of European bodies or those of the New World and Africa. Thomas Kren, in “The Nude and Christian Art,” explores the emergence of sensual bodies in Christian art, in figures such as Eve, Christ, David, Bathsheba, and Saints Sebastian and Agatha. As he notes, the majority of fifteenth-century nudes appear in religious art, though later in the century, secular nudes proliferated. For Christian figures, nudity generally implied virtue, as in Michelangelo’s male nudes, yet could be dangerous: reports of women aroused by a scantily clad Sebastian led, for example, to the removal of an altarpiece by Fra Bartolomeo.

Diane Wolfthal’s “From Venus to Witches: The Female Nude in Northern Europe” responds to scholarship that typically credits Italian artists with “inventing” the nude. Stating emphatically that fifteenth-century northern nudes did not derive from their southern counterparts and in fact pre-dated Italian experiments, she explores the nude’s origins in the North’s “rich and complex native traditions” (81). She notes fourteenth-century secular art included nudes, in bathing scenes, brothels, and images of the Fountain of Youth, for example. But by around 1400, particularly at the Valois courts, changes occurred, as such images became increasingly naturalistic, more ubiquitous, and the subject of easel paintings. While Italian artists focused initially on male nudes, northern artists like Jan van Eyck and Rogier van der Weyden developed the female nude. Although Italian influence became important for sixteenth-century northern artists, important differences remained. Partly influenced by the Reformation’s restrictions on religious art, artists like Lucas Cranach produced eroticized classical subjects, and – as a backlash against women around 1500 worsened their positions in society – additional misogynist themes proliferated: images of witches and of the Power of Women, for instance. Wolfthal’s essay, one of the strongest in the catalogue, offers a rich and convincing re-evaluation of the role of northern artists in the development of the nude as a subject.

C. Jean Campbell, in “‘Painting Venus’ in the Poetic Tradition of the Early Renaissance,” considers literary traditions concerning nudity, initially focusing her analysis on Ovid, the late medieval French court, and the thirteenth-century poem, Le Roman de la rose. Questioning Erwin Panofsky’s typically Neoplatonic interpretation of female nudes, where physical beauty reflects metaphysical beauty and virtue, Campbell writes of art that stimulates desire: “Painting Venus” in late medieval Europe served as a “synecdoche for amorous discourse” (119). She explores the early fifteenth-century Querelle de la Rose, the debate between nascent feminist Christine de Pisan and misogynist writers; the flourishing Ovidian tradition in Italy, seen for example in Bocaccio’s writings; and considers the humanist-poetic culture of Botticelli and Titian.

Stephen J. Campbell’s rich essay, “Naked Truth: Humanism, Poetry, and the Nude in Renaissance Art,” offers further perspectives. First focusing on the tension between Christians’ condemnation of nudes as licentiously pagan and humanists’ admiration for the classical world, Campbell offers the well-known humanist defense, where Neoplatonism sanitizes sensuous nudes by emphasizing their virtuous qualities. As Manuel Chrysoloras noted, viewing art was distinct from viewing real bodies, for seeing the physical beauty of the former allowed one to appreciate the beauty of the artist’s mind while the latter was mere carnal experience. More innovative is Campbell’s analysis of funerary monuments for scholarly men like Pius II and Jacopo Sannazaro, which included nude classical figures and personifications, either replacing Christian figures or located alongside them: Eros, Diana, and Apollo; the Three Graces; or Fame and Victory. Campbell’s consideration of recumbent nudes in landscapes delves into the sub-rational mind, the world of dreams and the passions generated in the fantasia (image-forming function) of the mind, and draws on poetry and classical literature as sources for these often enigmatic images.

Jill Burke’s excellent “The Body in Artistic Theory and Practice” offers a welcome focus on the male nude and its crucial role in European artistic theory. Further, she explores demands on Italian and northern artists to expand their working techniques, especially their use of drawings and the roles of both observation and canons of proportions, and to understand the relationship between nature and the divine. Her discussion of Vitruvius and human proportions considers distinctions between depicting women’s and animals’ bodies on one hand, and the perfect male body. As Cennini advises, the former two were to be drawn from life, while men were to be depicted via set measurements. She analyzes drawings by artists such as Pollaiuolo, Leonardo, Dürer, Gossaert, and Raphael; considers the rise of dissection and scientific studies of the human body; and raises the notion of artists improving upon nature, especially via their study of the nude.

Davide Gasparotto’s “The Renaissance Nude and the Study of the Antique” also discusses observation of nature as opposed to theoretical practices, but focuses on the role antiquity played for artists and their desire to surpass art produced by the ancients. Italian artists equated ancient art with high craftsmanship, and so judged it better than nature as models. Drawing upon written accounts of artists’ encounters with antique images, the discovery of works like the Laocoön, and upon extant sculptures and drawings, he analyses the role that the Greco-Roman tradition played in Italian Renaissance art.

Stephen J. Campbell, in “Unruly Bodies: The Uncanny, the Abject, the Excessive,” turns away from Renaissance bodies as idealized forms of virtuous beauty by exploring unidealized bodies – fantastic, macabre, or horrifying – by Hans Baldung Grien, Michelangelo, Bronzino, Dürer, and others. He explores self-portraits that display what he calls a corporeal understanding of the self; considers aging, suffering, and tortured bodies; and Wild Men and other marginal outsiders.

Ulrich Pfisterer’s “‘Here’s Looking at You’: Ambiguities of Personalizing the Nude” explores differences between male and female bodies, the head’s recognizability as opposed to the body’s, and public versus private viewing. Turning to Dürer and self-portraiture, he questions how representations could simultaneously be personal likenesses, yet also be idealized and symbolically meaningful. Accordingly, tomb figures, nude portraiture of both men and women, and eroticism in art are also examined.

The catalogue concludes with two Epilogues, Thomas Kren’s “Reformation and Beyond in Northern Europe,” and Thomas Depasquale’s “Michelangelo’s Last Judgment and the Reception of the Nude in Counter-Reformation Europe.” Kren considers the sensual nude’s longevity, seen in the sixteenth-century French court’s continued interest in erotic bodies and Reformation Germany’s conflicts over image making. The latter led not to suppression but to increasing interest in erotic art: as religious art declined, secular nudes proliferated, like those produced by Cranach and his shop. Based on recent scholarship, Depasquale finds the Counter-Reformation’s censorship of art “extremely sporadic” (368). He notes the Italian inquisition says nothing against nudes, and in fact rarely concerns itself with art (the famous Paolo Veronese case is an unusual exception). Indeed, the nude survives. As Kren concludes, artists’ interest in sensual nudes, beginning in the fifteenth century, “would influence profoundly the language of European art for centuries to come, an impact so pervasive that representations of naked bodies have become an expected feature of galleries and art museums” (363).

With its extensive bibliography, index, and rich essays, plus 112 detailed individual object entries, this catalogue offers great resources to scholars and students. More attention could have been paid to scientific theories about bodies, their procreation and gender difference; to the relationship of body to soul; as well as to the rise of dissections and scientific illustrations. Surprisingly the catalogue lacks sustained, focused consideration of additional “outsider” bodies – monstrous bodies or, most importantly, New World and Black bodies. On the positive side, perhaps most impressive is the attention to nudes both North and South, and assertions that not all major developments arose in Italy. Indeed, I suspect the most discussed artist in the catalogue is Albrecht Dürer. Overall, this exemplary catalogue offers extremely useful and intelligent perspectives on the Renaissance nude.

Penny Howell Jolly

Professor Emerita of Art History

Skidmore College