During the sixteenth century, a wealth of historiated stained glass filled the interiors of religious and secular buildings in the Netherlands, yet only a fraction of these luminous panes remains in Belgium today. While many factors including religious conflicts, changing fashion, and the fragility of the medium itself played a role in their loss, the widespread taste for the Gothic style in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries also contributed to this disappearance. By the first decades of the nineteenth century, dealers and collectors had shipped vast quantities of Flemish stained-glass windows to England, France, and the United States, where they were repurposed to adorn local churches and stately residences, or were acquired by museums, where many of them have since languished in storage.

Among these dispersed windows is one of the most important stained-glass cycles from the early sixteenth-century Netherlands, the spectacular glazings from the former Cistercian abbey of Herkenrode, which was located near the city of Hasselt in the province of Limburg. In the 1790s, French Revolutionary forces occupied the region, suppressing its religious communities, including the abbey at Herkenrode, and confiscating their assets. The nuns were forced to leave the Abbey, and it was finally put up for sale in 1797. The subsequent owners sold the Herkenrode glass to an English aristocrat who arranged the sale of the lion’s share to Lichfield Cathedral in England, where they were installed during the first years of the nineteenth century. A smaller group of panels from the Abbey are preserved in the Church of St. Mary, Shrewsbury (Shropshire) and the Church of St. Giles, Ashtead (Surrey). Other panes are now housed in private collections and in Het Stadsmus, the Hasselt city museum.

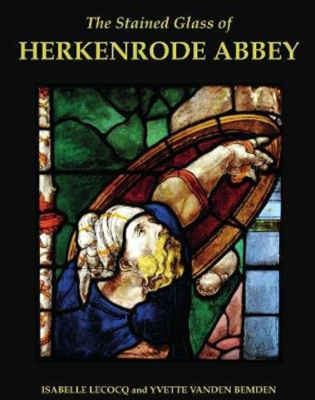

The Herkenrode windows are the subject of this weighty and meticulously researched volume written by Isabelle Lecocq and Yvette Vanden Bemden, members of the Corpus Vitrearum Belgium, in collaboration with colleagues from the Corpus Vitrearum Great Britain. This study, part of the Corpus Vitrearum’s ongoing series of publications documenting medieval and Renaissance stained glass, represents the first joint effort between the international committees, bringing together art historians, architectural historians, and conservators. (For a discussion of the Corpus Vitrearum international committees and for reviews of other volumes from the series, see this writer in the HNAR December 2021, April 2017, and April 2012).

In a lengthy general introduction, the authors reconstruct the windows’ original locations in the Abbey. The most important were those in the Abbey church and represented an extensive redemption cycle, beginning with the Annunciation and concluding with the Resurrection of the Dead, with the religious scenes inserted above registers depicting donors at prayer. The authors also discuss other glazings that were once in other parts of the Abbey, including the Abbess’s private chapel. The introduction further provides a detailed context for the windows, outlining a history of Herkenrode Abbey, its architecture, and the patrons and community associated with it. A wealthy institution in the 1530s and 1540s, the Abbey commissioned art of extremely high quality. To illustrate the Abbey’s taste for the modern Italianate style especially current in Antwerp, Lecocq and Vanden Bemden point to some of the many works in various media commissioned by the Abbess Mathilde de Lexy (1520-1548) and produced at the same time as the stained glass. Examples include majolica pavement tiles with Italianate ornament made in Antwerp in 1532; an antependium made in 1528-29, also in Antwerp, representing the Last Supper surrounded by an Italianate garland with ribbons on crimson velvet; and Lambert Lombard’s painting on canvas of Judith and the Head of Holofernes (now in Stokrooie, Church of St. Amand) from a series of Virtuous Women commissioned for the Abbey in 1547-48. In another example, in a manuscript made for the Abbess in 1544-48, the illuminator modeled his St. Bernard on the Antwerp artist Dirk Vellert’s 1524 engraving with its Italianate architecture and lavish antique ornament.

As Lecocq and Vanden Bemden show, the Herkenrode windows – works of great skill and accomplishment – also employ the current Antwerp style, and are extremely close to the oeuvre of the great tapestry designer and painter Pieter Coecke van Aelst (1502-1550), a dominant artist in the city. The windows’ similarities to Coecke’s dynamic figures and compositions have been long noted, but the extent of Coecke’s direct participation in their creation is not known. Archival documents record Coecke’s activity as a designer of monumental windows, and drawings for large-scale stained glass have been ascribed to him. Lecocq and Vanden Bemden examine Coecke’s drawings and paintings as well as the works in his circle, and while they are cautious about some of the attributions to Coecke, they analyze many striking connections between the Herkenrode glass and works associated with the artist. Questions of attribution are typically difficult in the medium of stained glass, which involves the collaboration of multiple specialists and may depart significantly from the original design in the course of its production. As Lecocq and Vanden Bemden amply demonstrate, however, the Herkenrode windows stem from Coecke’s powerful artistic personality. The authors suggest that Coecke and his shop were involved with the creation of the windows from their initial design to the making of the cartoons, and that Coecke himself, as an artist-entrepreneur, may even have supervised the glaziers himself. As works closely connected to Coecke, the Herkenrode windows expand our knowledge of his activity in a less-studied medium and deepen our knowledge of sixteenth-century artistic production in Antwerp. (For an overview of Coecke’s oeuvre, see also Stijn Alsteens, “The Drawings of Pieter Coecke van Aelst,” Master Drawings 52, no. 3 [2014]: 275-362, and Elizabeth Cleland, ed., with Maryan Ainsworth, Stijn Alsteens, and Nadine Orenstein, Grand Design: Pieter Coecke van Aelst and Renaissance Tapestry, exhibition catalogue, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2014). Lecocq and Vanden Bemden also situate the Herkenrode windows in their larger artistic milieu, comparing them to many other contemporary works, for instance, paintings by Bernard van Orley and the large-scale windows associated with Van Orley in the Cathedral of Saints Michael and Gudula, Brussels.

In addition to the sections on Herkenrode Abbey, the volume provides a detailed history of Lichfield Cathedral, and describes the restoration campaigns carried out on the windows, including the recent conservation completed in 2015. A major part of the volume comprises a catalogue of the Herkenrode windows, with extensive essays and important comparative material, beautifully illustrated in color.

This installment of the Corpus Vitrearum publications greatly advances our knowledge of Renaissance stained glass in the early sixteenth-century Netherlands. It also makes an important contribution to the study of Netherlandish drawings and other media, to the history of sixteenth-century monastic patronage, and to the understanding of the history of trade, collecting, and the international transport of sixteenth-century Netherlandish art works in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In addition, the authors highlight the importance of stained-glass design in the career of a major figure, Pieter Coecke van Aelst. By integrating stained glass into the wider context of painting, drawing, and printmaking of the period, this excellent study helps clarify our view of the Netherlands in the first half of the sixteenth century, and will be of great interest to all scholars of Northern European art.

Ellen Konowitz

State University of New York, New Paltz