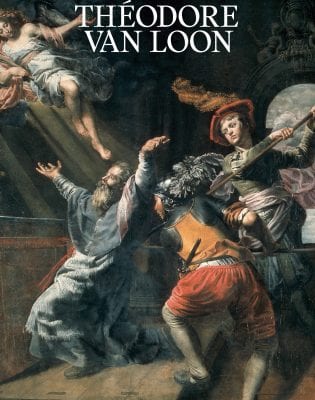

Despite the high esteem in which he was held by contemporaries in Italy and the Netherlands, the Brussels painter Theodoor van Loon (1581/82–1649) had until recently been largely ignored by modern scholars and the public at large. Fortunately, Sabine van Sprang’s 2018–19 exhibition held in Brussels and Luxembourg went a long way to remedy that injustice, bringing a conclusion to her and a fellow group of scholars and conservators’ initial study on the artist in 2011. The first ever monographic exhibition dedicated to Van Loon, the show brought together nearly thirty paintings, one drawing, and more than two dozen prints designed by the artist, in addition to a small group of paintings by Italian and Netherlandish contemporaries. It aimed to represent the core of Van Loon’s oeuvre: primarily large-scale religious paintings commissioned to satisfy the demand for devotional works in Brussels’ Catholic churches and monasteries in the early seventeenth century.

This review focuses exclusively upon the catalogue published to accompany the exhibition. Authored by Van Sprang and a team of experts, the book consists of seven wide-ranging and thoughtful essays followed by detailed entries on the paintings and graphic works chosen for exhibition. The catalogue offers fresh perspectives upon Van Loon’s artistic development, stylistic and iconographic models, painting materials, and technique, and provides new insights into the artistic, intellectual, and religious climate of the period. Van Loon emerges as a highly successful artist, one sought after and befriended by prominent figures at home and abroad. Not only did he earn the patronage of the Habsburg Archdukes Albert and Isabella, and work closely with their court artist Wenzel Coebergher, Van Loon won admission to a network of intellectual and ecclesiastical elites that included the German scholar and papal herbalist Johannes Faber, and the Flemish humanist Erycius Puteanus. In an unusual reversal, Peter Paul Rubens plays a minor role in this narrative, situated as Van Loon’s rival – if not his equal – and a member in overlapping artistic circles in Rome and Brussels. Tracing the arc of Van Loon’s career in this way, the authors position him as both witness to, and participant in a broader series of changes and innovations taking place across early modern Europe in the early seventeenth century, and one in which Italy played a reoccurring role.

The book opens with an essay by Van Sprang introducing Van Loon’s life and work and his distinctive approach to painting. As the author reminds us, documentary evidence pertaining to Van Loon is frustratingly sparse. No information survives about his education or training, or whether he operated his own studio in Brussels (the author suggests that he did, possibly after having worked under Coebergher). He never married, had no children, and moved repeatedly: he made no less than three trips to Italy – and possibly a fourth – over the course of his career (c. 1602–1608/1612; 1617; 1627/28; c. 1628–31), and called Brussels, Leuven, and ultimately Maastricht (where he died in 1649) home. Van Loon’s paintings are seldom dated, and many of commissions, which often came through Coebergher, leave little trace in the historical records. The author goes on to characterize Van Loon’s style as one grounded in tangible reality. It features sturdy, sculptural figures, rendered with “morphological exactness and refined execution,” designed, we are told, to awaken religious feelings in the viewer and encourage identification with the faithful (20). Although Van Loon occasionally borrowed thematic motifs from Rubens, according to Van Sprang, he largely eschewed the Antwerp artist’s complex synthesis of Italian, Flemish, and antique sources in favor of a blend of naturalism and classicism (19).

The following chapter, written by Irene Baldriga, explores Van Loon’s crucial early artistic influences and assesses the dynamic artistic climate of post-Tridentine Rome. Newly arrived in the city c. 1602, Van Loon lived on the Via di Ripetta not far from Santa Maria del Popolo, home to paintings by Caravaggio and Annibale Carracci. The author maintains that both Italian artists proved pivotal for Van Loon, providing sources for his handling of light and shadow, composition, and color. Equally significant for Van Loon’s stylistic development was the softer visual language of Federico Barrocci and Marco Pino, and later, the work of Guido Reni and Guercino.

Chapter three, also written by Baldriga, investigates Van Loon’s connections to the Accademia dei Lincei, the scientific academy founded by Federico Cesi in 1603. The author explains that, through his ties to members like Johannes Faber, Van Loon participated in several projects for the Accademia, including the design of the title page for the Animalia Mexicana, a treatise on the fauna of the New World published by Faber in 1628. This context provides a new lens through which to examine Van Loon’s commitment to naturalism, not only as a product of his own Flemish traditions, but also as an expression of the philosophical and empirical ideas he experienced in Rome.

The essay that follows, by Joost Vander Auwera, considers Van Loon’s contribution to the spread of Caravaggism in the Southern Netherlands. The Brussels painter represents the first generation of Flemish Caravaggists, along with Rubens and Abraham Janssen in Antwerp, but his engagement with this pictorial tradition – filtered through the work of other contemporaries – remained remarkably steady over his lifetime. This commitment, as Vander Auwera demonstrates, emerges most strongly in the effect of “relievo,” in which the use of chiaroscuro endows the figures with a powerful illusion of three-dimensionality (71).

Next, Ruben Suykerbuyk examines Van Loon’s paintings within the religious culture of the Southern Netherlands. The author’s starting point is Puteanus’s remark that Van Loon’s cycle of paintings in Scherpenheuvel seemed like “a theater of miracles” (73). In investigating the essential role of miracles in Flemish devotional culture, Suykerbuyk demonstrates the ways in which they strengthened beliefs and the sense of a collective Catholic identity. Van Loon’s paintings were thus not only of exceptional beauty, but they also stimulated and reaffirmed the miraculous experience of devotion itself. This argument underlines a point made earlier in Van Sprang’s essay – figures like Puteanus and Coebergher must have seen Van Loon as part of a larger, critical effort to introduce the “avant-garde” of post-Tridentine painting into the Low Countries (21). In this context, it is important to remember that it was Van Loon, and not Rubens, who had earned the commission for Scherpenheuvel.

In chapter five, a team of conservators at the Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage (KIK), including Claire Toussat, Paul Duquesnoy, Isabella Happart, Steven Saverwyns, and Charlotte Sevrin, presents the results of the restoration and technical investigation of five paintings by Van Loon undertaken for the exhibition. As the authors demonstrate, Van Loon adapted his materials and technique based on local traditions in Italy and the Netherlands. This research lends support to the new chronology of Van Loon’s work proposed by Van Sprang.

The essay section closes with a contribution by Hans Vlieghe considering the impact made by Van Loon’s art upon contemporary painting in and around Brussels. Vlieghe discusses the little-known artist Melchoir de la Mars, who, in 1621 in Ghent, made a direct adaptation of Van Loon’s Presentation in the Temple from Scherpenheuvel. He also points to works by Philippe de Champaigne, Michael Sweerts, and Michaelina Wautier that display – in varying degrees – elements of classicizing naturalism that Van Loon pioneered.

The exhibition catalogue Theodoor van Loon is a major contribution to the study of Brussels, one sure to serve as a springboard for further investigations. As the book shows, Van Loon was widely celebrated and admired by contemporaries. Yet while his solidly robust and naturalistic pictorial language served him well in the early decades of the century, his work lost some of its verve as time went on. Perhaps it was the painter’s reluctance to evolve that led art history to overlook him, or perhaps, as Van Sprang suggests in her essay, Van Loon did not find a place in a young nation still looking for its identity (19). The Archdukes would have likely disagreed. So would have Erycius Puteanus, whose description of Van Loon as “Apelles of the Netherlands” resonated throughout the painter’s long career.

Lara Yeager-Crasselt

The Leiden Collection