This memorial volume commemorates the accomplishments – many of them not visible in publications – of a leading Rubens scholar of his generation: Arnout Balis. Collecting his published articles around the Flemish painter and his circle, some of them in obscure anthologies and in Dutch, the editors foreground Balis’s lasting contributions: both sharp-eyed connoisseurship and methodology based in artistic process and workshop production, always exemplified in these selected articles.

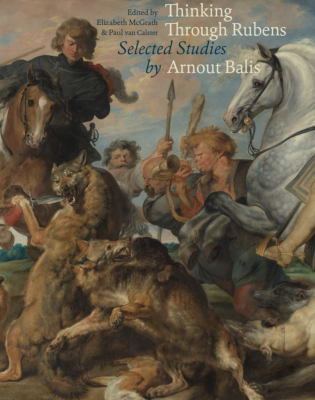

Regrettably, only one single-authored publication by Balis emerged from the Corpus Rubenianum Ludwig Burchard, his volume XVIII.2, Hunting Scenes (1986), based in turn on his 1983 dissertation at Ghent University. His own model catalogue for that ongoing series (begun 1968) was to be complemented by his opus magnum: the reconstruction of the ephemeral, largely lost, personal Notebook of Rubens. Two studies in this volume reveal his progress and discoveries in that pursuit, and a forthcoming Corpus volume (XXV), edited by Rubenianum colleagues, will complete his contribution for publication.

But Balis also made numerous invisible contributions, which inspired his colleagues with both admiration and affection: he meticulously edited Corpus volumes for other scholars with minimal credit. That selfless task salvaged several weaker contributions prior to publication and strengthened insights and analysis in even the very best volumes. Alongside professorships in both Antwerp and Brussels, Balis later assumed responsibilities as Chair of the Rubenianum and Editor in Chief of the Corpus before his untimely death (2021).

This collection of his work begins with a moving tribute to Arnout Balis by his close colleague, Elizabeth McGrath of the Warburg Institute, a renowned Rubens scholar in her own right, whose many studies on the painter include two celebrated Corpus contributions, her two-volume Subjects from History (Corpus XIII; 1997; edited by Balis) and her extensive participation in Mythological Subjects (XI, 2016, ongoing). Her warm, personal appreciation of his career (pp. 8-13) sets the scene for the articles that follow, in chronological order. The other co-editor of the volume, Paul van Calster, was Balis’s friend from childhood, a fellow scholar of Flemish art, and a book professional in his own right, both editor and designer. For both McGrath and van Calster, this posthumous volume was a labor of love.

At the heart of this volume and Balis’s lifelong research lie a cluster of articles fundamental to understanding Rubens and his workshop. The first, from a 1994 Tokyo exhibition catalogue (“Rubens’s Studio Practices Reviewed,” pp. 57-95) deftly analyzes Rubens’s studio practices; its revival alone is a lasting gift to Rubens scholarship. Of course, this issue remained central to his beloved hunt scenes but also addressed the basic project of his beloved Corpus Rubenianum.

Balis’s analysis includes collaboration with a precocious Anthony van Dyck on several works (1617-20): the celebrated Coup de Lance (Antwerp; now accepted by the museum); the cartoons for the Decius Mus tapestries (Liechtenstein Collections, Vaduz–Vienna); plus the lost panels of the Antwerp Jesuit Church. One documented figure, Willem Panneels, copyist of Rubens cantoor figural studies,[1] also returns in one of Balis’s last short studies, fittingly published in the Rubenianum Quarterly (pp. 181-189, 2020). Other artists, such as Abraham van Diepenbeeck, are cited as surely figuring in later painting productions. Raphael in Rome and Frans Floris in Antwerp provided the template for such processes.

Of course, massive late Rubens projects, the Triumphal Entry of Ferdinand and the Torre de la Parada, are well documented, and some collaborations with established, “specialist” painters, led by Jan Brueghel the Elder and Frans Snyders, are visually obvious and deliberate as a delight for connoisseurs (liefhabbers).[2] But Balis sets out a spectrum of authorial participation, ranging from fully autograph works to delegated assignments to assistants via oil sketches. Along with his full command of scholarship, Balis uses primary documents, including Rubens’s letters, as he distinguishes between apprentices, assistants, and collaborators, seeking to dispel a simple, commonplace assumptions of a studio “factory,” an assembly line of production by “pupils” on those massive canvases.

Much of this material is reprised in “Rubens and his Studio. Defining the Problem” (pp. 149- 179), which stems from a 2007 Brussels Rubens catalogue. It provides a meticulous survey of names mentioned in documents. Once more Balis closely examines the organization of production by Rubens, distinguishing between autograph works, larger but harmonious workshop participation (varied according to the patron, the size of the assignment, and the workshop assistants on hand), along with overt collaboration with recognizable specialists. A final section of the essay sorts out shifting roles in definable phases of Rubens’s career.

Balis’s last word on the subject, “Many Hands in Rubens’s Workshop” (pp. 191-209, 2021), appeared in an anthology, Many Antwerp Hands, devoted to collaborations. Appropriately that volume resulted from its own Rubenianum conference (2018).[3] Here he offers more complex assessments of the Decius Mus series and the Marie de’ Medici cycle, while calling for closer inspection of individual canvases, especially around the uncredited role of Van Dyck. Again he reminds us about how many social and economic considerations, even viewing locations, could shape the degree of workshop participation in a picture or series while following the range of preliminary steps in the process of production. We see in this swan song how Balis resonated with Rubens’s working methods as he embodied the fundamental goals of the entire Corpus Rubenianum.

In addition, Balis provided a broader synthetic overview of designs used for various media, including cartoons for tapestry and stained glass, along with studies after nature and head studies, tronies. That essay, “Working It Out: Design Tools and Procedures in Sixteenth- and Seventeenth-Century Flemish Art” (pp. 97-121, 2000), was featured in a volume that he co-edited. It remains valuable.[4]

Closer up, Arnout Balis’s pet project was reconstructing the lost Rubens Notebook, once viewed by Roger de Piles, who transmitted an important text, “On the Imitation of Ancient Sculpture in Paintings.” His progress appears in two articles. One analyzes a recently rediscovered single-sheet drawing (Phoebus Foundation, Antwerp) for its Roman sources (“A Sheet from Rubens’s Theoretical Notebook,” pp. 210-218, 2021).[5] But Balis’s more ambitious outlook appears in “Rubens and Inventio. The Contribution of his Theoretical Notebook” (pp. 122-147; recovered from a German publication, 2001). Rubens included both ink drawings of motifs and physiognomy as well as literary quotations, reflecting on his depiction of human passions for grand narratives. Balis pursues his clues like a detective, comparing varied copies and paraphrases, including a Chatsworth notebook of drawings, ascribed by Michael Jaffé to young Van Dyck.[6]

Two other articles of this book present Balis juvenilia about animals: “Hippopotamus Rubenii: A Small Chapter in the History of Zoology” (pp. 14-27, 1981); and “Picturing Fables in Seventeenth-Century Flemish Painting,” (pp. 39-54, 1985). The former was presented on the occasion of the opening of the Rubenianum, while the latter was rescued from an obscure catalogue of animal pictures, Zoom op Zoo, held at the nearby Antwerp Zoo, showing Balis’s engaged local outreach.

To savor Balis’s insights in a related field, one should seek his several studies on Van Orley’s tapestry designs for the so-called “Hunts of Maximilian.” That work was based on his 1980 Master’s thesis, a kind of prequel to his dissertation on Rubens’s hunts. Here (Gentsche Bijdragen 25, 1979-80, pp. 14-41), he offers a critical corrective to work by Sophie Schneebag-Perelman, from which he went on to collaborate in the tapestries’ definitive publication with Guy Delmarcel and other Belgian experts about Van Orley’s role for the series (1993). Balis also co-edited a New Hollstein catalogue about the Collaert printmaking family (2005), and he co-authored the Corpus Vitrearum volume on the stained glass of his hometown cathedral in Brussels (1994).

Many other edited volumes, easily overlooked but crucial interventions, are listed in a roster of principal publications. As they readily reveal, the loss of Arnout Balis is keenly felt by many of his own collaborators and even more of his colleagues.

Larry Silver

University of Pennsylvania

[1] Paul Huvenne and Iris Kockelbergh, eds., Rubens Cantoor, exh. cat. (Antwerp: Rubenshuis, 1993).

[2] Elizabeth Honig, “The Beholder as Work of Art: A Study in the Location of Value in Seventeenth-Century Flemish Paintings,” Nederlands Kunsthistorisch Jaarboek 46 (1995), pp. 252-297; also Honig, in Abigail Newman and Lieneke Nijkamp, eds., Many Antwerp Hands: Collaboration in Netherlandish Art (Turnhout, 2021), pp. 163-171 (reviewed in this journal by this reviewer, October 2021).

[3] Newman and Nijkamp, Many Antwerp Hands.

[4] Hans Vlieghe, Arnout Balis, and Carl Van de Velde, eds., Concept, Design & Execution in Flemish Painting (1550-1700) (Turnhout, 2000), pp. 129-151.

[5] Also discussed by David Jaffé with Amanda Bradley, “Rubens’s ‘Pocketbook’: An Introduction to the Creative Process,” in Jaffé et al., eds., Rubens A Master in the Making, exh. cat. (London: National Gallery, 2005), pp. 21-27; now see D. Jaffé, “Rubens im Werden,” in Becoming Famous: Peter Paul Rubens, exh. cat. (Stuttgart: Staatsgalerie), pp. 51-63, also the source of Balis’s study.

[6] Michael Jaffé, Van Dyck’s Antwerp Sketchbook (London, 1966).