As points of transition, thresholds offer new possibilities, but they also mark boundaries, divisions of time and space. Employing the anthropological theories of Arnold Gennep and Victor Turner, who extensively studied rites of passage, Lynn Jacobs investigates the liminal character of Netherlandish art. In the introductory chapter, she highlights numerous ways in which visual images have functioned as thresholds. Jacobs also calls attention to the ambiguous and paradoxical character of Netherlandish art placed betwixt and between various realms of time and space.

In the second chapter, Jacobs addresses the Chartreuse de Champmol as a threshold of death, where living monks offer prayers and perform masses for their deceased benefactors residing in purgatory. Jacob notes that the figure of Mary (porta coeli) appears to be turning from the portrait of Philip to her child. Her gesture elicits the possibility of divine intervention. The donors are accompanied by John the Baptist and St. Catherine rather than their patron saints. Jacobs suggests that the two saints represented, which are closely associated with the Valois dynasty and readily linked to Final Judgment, may have been placed there to assure continuation of the ducal line and to ensure the salvation of the individual souls of its family members. Inside the Carthusian monastery’s choir, an image of the recumbent duke is carved atop his tomb. Surrounded by monochromatic mourners, the open-eyed duke is presented in color, evoking his entrance into the glories of heaven. The Well of Moses, with its sacramental associations, functions as a fons vitae, providing an opening for everlasting life.

Next Jacobs turns her attention to the way in which thresholds can divide, rather than unite, spaces. In the third chapter, she discusses how the boundary of class is reinforced in the calendar pages of the Très Riches Heures, suggesting that in the February and March pages, the peasants reside within restricted spaces. By contrast, aristocrats rendered in the January and April pages appear to be placed in front of scenes. The setting is reduced to a backdrop, one often under their control. She also notes the strong divisions between fields and castles and those between labor and leisure depicted throughout the calendar. At the close of the chapter, Jacobs compares this manuscript to contemporary codices, the Luttrell Psalter and the Rohan Hours. None of these books makes any reference to peasant uprisings. Instead, they all affirm the status-quo, calming aristocratic anxieties concerning social mobility, foreclosing the possibility of political and economic change.

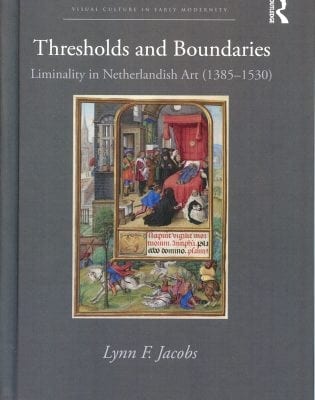

The fourth chapter investigates the use of thresholds and boundaries in manuscript illuminations. Jacobs notes that the layering of complex spatial relations in books attributed to the Master of the Dresden Prayer Book, the Master of the Mary of Burgundy Hours, and other Ghent–Bruges painters map out various meanings within a single page as they juggle multiple views of reality, representing objects in ways that affirm the two-dimensionality of the page as well as objects that deny it, seeming to appear in virtual space. Not only do these pictures offer effective ways of communicating ideas through metaphorical associations, they also do so in a manner that manifests and places greater value on artistic inventiveness. The interplay of perspectives within single illuminations is further complicated by the turning of pages, opening and closing pictorial possibilities of meaning. Playing off the expectations of the beholder, painters are appreciated for their ability to elicit surprise and wonder.

In the fifth chapter, building on her book Opening Doors: The Early Netherlandish Triptych Reinterpreted (2012), Jacobs discusses the function of altarpieces as thresholds. She draws attention to the use of grisailles exteriors to suggest a liminal space between the actual appearance of the church interior and the colorful depiction of the interior panels of altarpieces. She also notes that the themes addressed on exterior wings, such as the Annunciation and Last Judgment, are often readily associated with thresholds. In addition, altarpieces, placed behind sacramental tables, reinforce participation in the Eucharist, itself a threshold conferring divine grace.

Jacobs closes the book with a coda focusing on seventeenth-century Dutch paintings of domestic interiors as evoking liminal spaces. Moving her attention from the church to the home, she addresses preoccupations with romantic love and social class. She particularly analyzes the work of Jacob Ochtervelt, who depicts scenes occurring in the voorhuis (foyer) of wealthy homes, a place between home and street, private and public, where the urban rich and poor confront one another. Another point of discussion is the significance of staircases in the genre paintings by Nicolaes Maes. These liminal places are related to lucidity or playfulness, where naughty, eavesdropping domestic servants humorously observe the tension between love and lust. In addition, Jacobs considers the significance of doors and windows in the work of Pieter de Hooch. She ends the coda with a discussion of Rembrandt’s Return of the Prodigal Son, pointing to the juxtaposition between the promised interior of the father’s home and the outside world. Beholders are invited to step into the threshold of the painting’s foreground and imaginatively identify themselves in the role of the reckless son now seeking forgiveness and salvation. Surprisingly, Jacobs does not address the work of Pieter Saenredam or Emmanuel de Witte. Their depictions of church architecture also elicit notions of the private and public, the sacred and the profane.

Although Jacobs does not offer substantially new interpretations of particular works, her book rightfully encourages readers to look more closely at the dynamics of thresholds and boundaries at play in early Netherlandish art. Perhaps more importantly, her work offers a strong reminder to see the multivalent character of these images. The significance of ambiguity and play should not be underestimated. Her book addresses Netherlandish art, but it invites readers to think about other visual thresholds. For instance, Byzantine icons are often described as passageways or as windows revealing the presence of the divine. How do these sacred images compare and contrast to Netherlandish depictions of the Holy Face and the representations of particular saints? Jacobs does not discuss the genre paintings of sixteenth-century Netherlandish artists such as Jan Sanders van Hemessen and Pieter Aertsen. Yet their imagery often plays on tensions between foreground and background. Did their work open the door for seventeenth-century depictions of liminality? Finally, Jacobs evokes a closer examination of the development of the self in early modernity, to reconsider personal interiority as a threshold and as a boundary. Her book, like the liminal images that Jacobs addresses, unveils new opportunities of further discussion without foreclosing the allusive quality of early Netherlandish art.

Henry Luttikhuizen

Calvin College