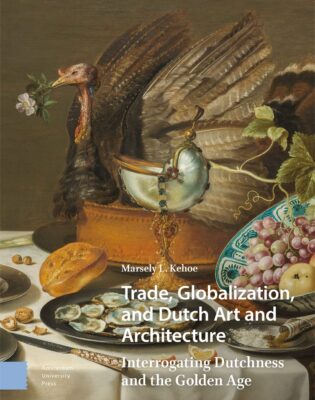

Marsely Kehoe begins her recent monograph, Trade, Globalization, and Dutch Art and Architecture, with two big claims: that the Dutch Republic’s global reach was key to the cultural as well as the economic flourishing of the young nation, and that the importance of this global framework has been forgotten in art historical scholarship on the so-called Dutch Golden Age. Whereas the first appears inarguably true, and is supported here, the second requires some qualification. In recent decades, the study of Dutch Art has been gradually but inexorably changed by the so-called ‘global turn’ in the humanities. Important English language contributions to this development include Rebecca Parker Brienen’s 2006 Visions of Savage Paradise, Julie Hochstrasser’s 2007 Still Life and Global Trade in the Dutch Golden Age, the 2011 exhibition Asian Splendour: Company Art in the Rijksmuseum and the 2015/16 exhibitions Asia in Amsterdam held at the Rijksmuseum and the Peabody Essex Museum, as well as that same year, Netherlandish Art in its Global Context, volume 66 of the Nederlands Kunsthistorisch Jaarboek. These investigations rest upon key historical and cultural studies by scholars such as Hannadea van Nederveen Meerkerk, Leonard Blussé, Peter J. Whitehead and Marinus Boeseman, Kees Zandvliet and Jean Gelman Taylor, to name a few.[1] Although it is somewhat overstated, Kehoe’s assertion here rings true and there still is work to be done in recovering the central role that overseas trade, the slave trade, and settler colonialism played in the history of Dutch art of the so-called Dutch Golden Age.

Kehoe’s book consists of an introduction, four body chapters and a brief conclusion. Helpfully, each chapter includes an abstract and its own works cited, making the volume easy to navigate and particularly useful for teaching. A key contribution of her study is the concept of ‘Dutching’ – the act of moving towards an ideal of Dutchness. This notion is explored in chapters on nautilus cups, ‘pronkstileven’, the urban design of Batavia and the more recent marketing of Willemstad in Curaçao. Kehoe explores the complex ways ‘Dutching’ could be accomplished. In the case of nautilus cups, she contends, for example, that the nautilus shell’s elaborate metalwork mounts produced by goldsmiths in Utrecht, Delft and Rotterdam made these natural objects, which were taken from across the globe, Dutch via the act of mounting, carving and adding designs.

However, there is more to unpack here on the motivations for this process. In her second chapter on nautilus cups, for example, how could a period viewer distinguish between Dutch and the just as common German silver-gilt mounts for these rare shells? How did period viewers understand the multinational reality of the Dutch East and West India Companies both of which employed English, French, German and Swedes, as well as numerous non-Europeans? How is ‘Dutching’ policed: can we claim to move towards a ‘decolonial’ art history (19) without interrogating the assumption that Blackness must be separate from Dutchness – especially as the work of Mark Ponte, Elmer Kolfin and others has demonstrated that there have long been Black residents of Amsterdam and other Dutch cities, among them Black employees of the VOC and WIC.[2] The author is remarkably self-reflexive on her own subject position, but in the introduction and first body chapter, it would be helpful to have more primary sources reflecting on Dutchness as a concept and a definition. For example, of the 10% of Batavia’s population considered to be ‘Dutch’ in 1673 [153], the following questions could be asked: Who were these individuals? How were their identities determined? Was Dutchness defined differently in Batavia than in Amsterdam? Considering questions like this, alongside specific archival examples, would have historically grounded the author’s rehearsal of historiographic and theoretical writing about identity politics.

Nautilus cups are a somewhat counter intuitive choice for Kehoe’s first case study as they are a relatively small corpus, in contrast to say the millions of pieces of porcelain or objects made in brazilwood that were consumed and used in the Dutch Republic. As luxury objects, it is less clear how they engender ‘daily intimate interactions’ (40). Kehoe attempts to use these exquisitely mounted nautilus shells as a model for how global goods ‘framed’ Dutchness in the seventeenth century. In the following chapter, she turns to the luxury still life paintings of Willem Kalf and his ilk. After a useful rehearsal of the considerable and varied literature on Dutch still life paintings, Kehoe delves into the availability of pepper in the Dutch Republic to argue that the ‘showing off’ of such paintings (which often prominently feature pepper) “suggest[s] an anxiety that the wealth is slipping away” (109) in the 1660s. Although more evidence would be needed for me to accept her claim fully, Kehoe’s analysis calls attention to the economic ups-and-downs of the Dutch seventeenth century, particularly as Dutch maritime dominance was threatened by rival commercial empires, particularly the English.

The final body chapters shift from goods exported into the Netherlands to consider urban planning outside of Europe. Kehoe is on firmer ground here, exploring how the new city of Batavia simultaneously reproduced and undermined supposedly Dutch values of civic and social life, concluding that “What separates Dutch planning in the Republic from that in the colony is only the degree, not the presence, of hierarchy” (152). Kehoe provides a useful, teachable study of Batavia as a Dutch city. The following chapter follows this logic across the Pacific to the Caribbean, to consider how Willemstad has been made more Dutch in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries through practices of selective preservation and promotion that emphasize Dutchness. Kehoe draws parallels between the curvy gables of Willemstad’s townhouses and those found in Dutch communities in South Africa (186), while seeking to highlight the contributions of enslaved Africans, the Jewish diaspora and indigenous peoples to the city’s colonial architecture, in a counter-narrative to how Curaçao is promoted as a tourist site of Dutch colonial nostalgia. Here, and in the brief conclusion to the volume, Kehoe describes how Dutchness is marketed by communities both inside and outside of the Netherlands, taking her critique of the ‘Golden Age’ to its modern proponents.

Although the focus of the volume is primarily on the seventeenth century, it is in these final chapters on the modern rebranding of global Dutchness, where Kehoe’s claims feel the most innovative. While the importance of the Dutch trading companies is now regularly taught as part of our surveys of seventeenth-century painting (even featuring in preparatory materials for US high schooler’s AP Art History exams), there is still much work to be done documenting and analyzing the ways in which Dutch visual, material and built cultures were shaped by global commerce, enslavement, and colonial extraction. In its focus on still life painting, exotic trade goods, and the architecture of Dutch overseas trading posts, Trade, Globalization and Dutch Art and Architecture feels somewhat belated, representing something of the end of a productive first wave of art historical scholarship, but one which begins to indicate future potential trajectories for the study of early modern Dutch art, less focused on luxury, gift-giving and the export of Dutch models in favor for interrogating the very concept of ‘Dutchness’ in a global frame.

Stephanie Porras

Tulane University

[1] Hannadea van Nederveen Meerkerk, Recife: The Rise of a 17th-Century Trade City from a Cultural-Historical Perspective (Assen, The Netherlands,1989); Peter J. Whitehead and Marinus Boeseman, A Portrait of Dutch 17th-Century Brazil: Animals, Plants and People by the Artists of Johan Maurits of Nassau (Amsterdam, 1989); Jean Gelman Taylor, The Social World of Batavia, European and Eurasian in Dutch Asia (Madison, WI, and London, 1983); Kees Zandvliet, Mapping for Money: Maps, Plans and Topographic Paintings and Their Role in Dutch Overseas Expansion during the 16th and 17th Centuries (Amsterdam, 2002); Thomas DaCosta Kaufmann and Michael North, eds., Mediating Netherlandish Art and Material Culture in Asia (Amsterdam, 2014).

[2] See Elmer Kolfin, “Rembrandt’s Africans,” 376-85 in David Bindman, Henry Louis Gates, & Karen C. C. Dalton, eds., The image of the Black in western art. – New ed. – Vol. 3, pt. 1: From the ‘age of discovery’ to the age of abolition: artists of the Renaissance and Baroque (Cambridge, MA, 2011); Elmer Kolfin & Esther Schreuder, eds., Black is beautiful: Rubens tot Dumas (Amsterdam, 2008); Elmer Kolfin and Epco Runia, eds., with contributions by Stefanie Archangel, Mark Ponte, Marieke de Winkel, and David de Witt, Black in Rembrandt’s Time, exh. cat., The Rembrandt House Museum, Amsterdam, March 5 – May 31, 2020 (Zwolle, 2020).