This slim volume is a catalogue of an “in focus” exhibition, centered around Jan de Beer’s double-sided panel of Joseph and the Suitors and The Nativity in The Barber Institute of Fine Arts, Birmingham (England). This exhibition – only the second exhibition solely devoted to the work of Jan de Beer, after the 2011 exhibition in the National Gallery in London – is the first to bring together all the de Beers in the United Kingdom (plus one workshop piece, Catalogue #4). The exhibition catalogue represents a very welcome addition to the recent body of scholarship that has significantly advanced our understanding of Antwerp Mannerism and of Jan de Beer in the wake of the 2005 Extravagant exhibition catalogue, headed by Peter van den Brink, and the groundbreaking 2016 Jan de Beer monograph by Dan Ewing.

The catalogue includes three excellent short essays, which provide readers with a useful introduction to the artist’s paintings and drawings, along with new insights and up-to-date discoveries about stylistic development, iconography, technique, and collecting history. The first essay, by Dan Ewing, gives an overview of the material in his monograph, beginning with a consideration of the evidence of de Beer’s fame during his time and an assessment of the reasons for his later obscurity. Ewing explains clearly the nature of the Antwerp Mannerist style, with its focus on artifice, elegance, artfulness, and chromaticism, and he charts how de Beer’s works demonstrate the importance of religious art in Antwerp, even at a time when new, non-religious pictorial genres, such as landscape painting and social genre, were emerging. Ewing situates Antwerp Mannerism as a new and modern expression of the Gothic style, which did not survive past the 1530s, in opposition to the Renaissance trends, already found in some of de Beer’s artistic contemporaries, which would carry on through the later part of the century.

The last section of Ewing’s essay is devoted to the specific works in the exhibition. Ewing’s discussion of the Barber panel considers its function as a part of a painted wing of an enormous sculpted altarpiece. Given the quality of the Barber panel and its sophisticated iconography, Ewing is fully justified in concluding that the original intact altarpiece would have been one of the most impressive altarpieces produced in Antwerp in its day. Regarding The Adoration of the Magi, formerly owned by James Stillman (Catalogue #3), Ewing here revises his dating from de Beer’s early period to his middle period, based on newly available underdrawings made in conjunction with the work’s 2016 cleaning. The exhibition allowed viewers for the first time to see this work, which had not been seen by scholars for over a century, in its restored state.

The volume’s second essay is Peter van den Brink’s study of Jan de Beer’s drawings. Van den Brink presents a corpus of ten autograph drawings; since he does not accept the St. Jerome in His Studio in Rotterdam and also elevates The Penitent St. Jerome in London and The Birth of the Virgin in Frankfurt from workshop status, his corpus differs slightly from Ewing’s corpus of nine works. Van den Brink also examines nine underdrawings, considering changes in style over time, which proves helpful with dating and occasioned the re-dating of the Stillman painting, noted above. One of the most stimulating parts of Van den Brink’s essay is its attention to the differences between the roles of drawings and underdrawings, and the impact of these differences on drawing style. Hopefully this discussion will prompt further comparative studies of these two graphic forms for other artists who have an established oeuvre of both drawings and underdrawings.

The final essay in the volume, Robert Wenley’s examination of the collecting of Jan de Beer in England, provides fascinating insights into the acquisition of Netherlandish painting in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century England. The collector John Strange is thought to be responsible for bringing the first Jan de Beer painting to England. Strange acquired the Virgin Triptych (Catalogue #2) from a Venetian family before 1789, and the triptych in 1800, or at least by 1821, came into the collection of the Earl of Radnor of Longford Castle, who owned a number of other important Northern paintings, including Hans Holbein’s French Ambassadors. The Earl of Radnor considered his de Beer painting to be a Dürer, though in 1909 the painting’s attribution was updated and, like many Antwerp Mannerist paintings, given anew to Herri met de Bles, until Friedländer correctly attributed it in 1933. Although the Virgin Triptych, currently still at Longford Castle, is the first documented de Beer painting in England, Wenley thinks that the Barber painting may have been imported into England even earlier, perhaps when it was acquired by Sir John Frederick of Burwood Park around 1732. But, as Wenley argues, the collecting of Netherlandish sixteenth-century paintings and Antwerp Mannerists seems to have been most popular in England after the mid-nineteenth century, during the Victorian era, when tastes favored both religious art and art that was considered “primitive.” One oddity of all the collecting of de Beer’s works in England is that none of the collectors knew that they were collecting a work by that specific artist, because that artist’s identity had become so completely obscured over time.

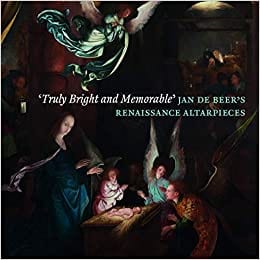

The catalogue section of this book treats the four paintings and three drawings on display in the exhibition, with the entries divided between Ewing and Van den Brink, respectively. These entries are succinct, clear, and well illustrated. All in all, the catalogue and the accompanying exhibition demonstrate the strengths of the “focus exhibition” format. Moreover, in focusing on the Barber panel – a work with gorgeous coloring and spectacular lighting, which represents the Antwerp Mannerist style at its very finest – the catalogue fully justifies Lodovico Guicciardini’s 1567 description of Jan de Beer as “truly bright and memorable.”

Lynn F. Jacobs

University of Arkansas