As psychologists have long known, there is no visual experience more powerful than coming face-to-face with another human being. It is not surprising, then, that human physiognomy has occupied artists and art theorists of the Western tradition for millennia. Yet, while portraiture, understood to represent specific historical persons, has dominated the genre of face painting since antiquity, early modern artists were evidently the first to cultivate the anonymous face or figure as a motif worthy of interest. As studies by Franziska Gottwald, Dagmar Hirschfelder, and others have shown, Dutch and Flemish artists played a strong role in this development.

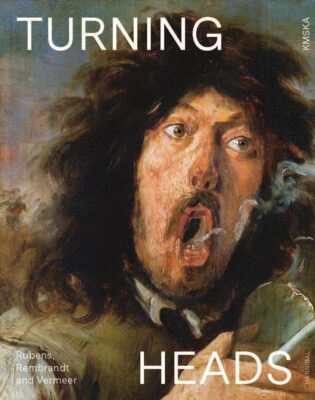

Lacking a precise translation, the term ‘tronie’ (colloquial Dutch for ‘face’) has become common in both English and Dutch to identify a pictorial category loosely defined as an autonomous study of the human head or face. Paintings of this type formed the subject of an engaging exhibition held at the Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Antwerp and the National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin. This writer saw the exhibition in Dublin, where the presentation was organized in five sections aligned with themes treated in the catalogue, such as studies intended for larger works, expressions of emotion, and the uses of evocative costume. According to promotional materials, the Antwerp installation was also presented in five sections. Beginning with a small prelude of fifteenth-century works and ending with a few nineteenth-century examples, it featured 78 objects from 43 lenders, anchored by the work of Rubens and Rembrandt. Unfortunately, the catalogue (in English and Dutch) does not provide a checklist or indicate to readers which of the works illustrated were presented in the show. (This is a frustrating trend in recent exhibition publications, perhaps driven by logistics, such as the need to send books to press before lending agreements are confirmed.)

This exhibition made an important contribution by bringing together Flemish and Dutch examples of the genre. In the introductory catalogue essay, Koen Bulckens and Nico Van Hout argue that sixteenth-century Flemish artists, especially Pieter Bruegel and Frans Floris, originated the tronie, later popularized by Dutch artists such as Rembrandt. The scope of the exhibition reflected this claim, while the catalogue expands further with an essay by Michael W. Kwakkelstein on the physiognomic ‘grotesques’ drawn by Leonardo da Vinci, an important source for Northern artists such as Quentin Massys and Albrecht Dürer. (In 2023, Massys’s Leonardesque caricature of female old age was the focus of a small exhibition at the National Gallery, London. The catalogue, The Ugly Duchess: Beauty and Satire in the Renaissance, edited by Emma Capron, makes a useful complement to the volume reviewed here.)

From Adriaen Brouwer’s Bitter Potion (Städel Museum, Frankfurt) to the Rembrandtesque Man in a Golden Helmet (Gemäldegalerie, Berlin), each painting presented is appealing in itself, but what, exactly, holds these works together? Bulckens and Van Hout rightly observe that the definition of the tronie as a pictorial genre is fraught with complications. While the word ‘tronie’ was used broadly in period documents, modern scholars have attempted to refine it, perhaps (the authors argue) too closely, to distinguish it from portraits and other images in which the human head plays a central role. Bulckens and Van Hout aim “to bring clarity” to the question of what sets the tronie apart from other categories such as portraits, head studies created in preparation for more complex compositions, and single-figure genre and history paintings. However, their choice of representative examples only obfuscates their case. The authors claim that Rembrandt’s Laughing Man (Los Angeles, J. Paul Getty Museum) “poses no problem” as a tronie and that Rembrandt’s “main aim … was for the work not to be recognised as his self-portrait” (11). Yet, among Rembrandt specialists, the reasons for his prolific depiction of his own features have been hotly debated. As the present writer and others have argued, Rembrandt’s features were recognized by well-informed connoisseurs, providing added value alongside his virtuosic depictions of form and feeling.

Among Flemish prototypes, Bulckens and Van Hout focus on several works in which Abraham Grapheus, messenger for the Antwerp Guild of St. Luke, served as model. Here they identify as a ‘pure’ tronie a sketch by Anthony van Dyck, now in the Gemäldegalerie, Berlin, that presents Graphaeus with face turned heavenward. It seems to me, however, that although no accessories identify this figure (as in other works where Grapheus impersonates a specific apostle), Van Dyck must surely have asked Grapheus to hold this pose with a devotional subject in mind. The same reverent face appears, for instance, in Van Dyck’s Descent of the Holy Spirit in Potsdam. Thus, the small panel was likely not an independent tronie but a preparatory sketch defining an emotive character for future use. In a second essay, Van Hout delves further into the function of head studies as preparation for multi-figured history paintings, originating around 1400 and culminating in the extensive cast of characters kept for collective use in Rubens’s workshop and only sold after the master’s death. While Van Dyck’s pieced-together panel in Berlin was enlarged later on, presumably for sale, surely the addition of praying hands only reinforces a saintly identity. Does this make the enlarged panel a tronie, then, or a single-figure history painting? In this writer’s opinion, these ambiguities suggest that the tronie as a category is still as slippery as ever.

The rise of the tronie in Dutch seventeenth-century art has been closely associated with the workshop shared in Leiden in the late 1620s by Rembrandt and Jan Lievens. A key point is that the two young artists marketed their head studies as autonomous objects from the start (not preparatory sketches that later became collectibles). In an essay on costume, Lizzie Marx explores how Rembrandt and others used exotic fabrics and accessories to create quasi-historical types that defy precise definition yet clearly exist outside quotidian reality. The results reflect prototypes by artists such as Lucas van Leyden, Floris, and Rubens, as well as encounters with foreign goods and visitors. (One of their best-known types, the richly turbaned character identified in period sources as a ‘Turkse tronie’, will be explored in an exhibition forthcoming at the Rembrandthuis.)

Sixteenth-century Flanders (not the Dutch Republic) may well have been the birthplace of the tronie, but the earliest examples were largely either generic (Bruegel) or idealized (Floris). The tension between stereotype and individual creates another conundrum. Is a conventional social type (‘the jester’, ‘the crone’) a tronie, or a single-figure genre subject? As Friederike Schütt explores in an essay on depictions of emotion, seventeenth-century artists developed a more varied and broadly evocative repertoire of faces. Yet, she suggests that didactic intent may still have informed depictions of coarse emotions that contrasted with the Neo-Stoic ideal of self-control.

Apart from emotion, the ways in which tronies might reflect on aspects of the human condition (gender, class, age) receive scant coverage in these essays. Attention is given to their status as demonstrations of virtuosity; Bulckens devotes an essay to the depiction of light and shade. Short ‘reflections’ round out the catalogue with musings on the human face by contemporary psychologists, artists, an actor, and a hat designer.

Since the mid twentieth century, the fields of Dutch and Flemish art scholarship have become increasingly polarized. Few scholars today have the breadth of learning demonstrated by Julius Held, Egbert Haverkamp-Begemann, or J. Richard Judson, all of whom published on major Flemish as well as Dutch artists of the early modern period. More cross-cultural projects like Turning Heads could surely produce welcome new insights into the fertile exchange between Dutch and Flemish artists that flourished despite the Dutch Revolt and its political consequences.

Stephanie S. Dickey

Queen’s University, emerita