Many readers will have shared my disappointment at having missed the exhibition Van Eyck: An Optical Revolution, which opened at Ghent’s Museum voor Schone Kunsten on February 1st, 2020, and was scheduled to end on April 30th, but closed early on March 12th due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The phrase “once in a lifetime” gets tossed around rather carelessly when it comes to blockbuster exhibitions, but in this case it really does seem inconceivable that any of us alive today will witness so many of Jan van Eyck’s paintings – more than half of his extant oeuvre, including several newly-cleaned panels from the Ghent Altarpiece – gathered under one roof again. Those not fortunate enough to visit Ghent before the show’s premature closure can be grateful, at least, for thorough and thoughtful exhibition reviews by Susie Nash and Lorne Campbell (in the March and April 2020 issues of Apollo and The Burlington respectively), for the virtual tour of the show uploaded by the Ghent museum (https://virtualtour.vaneyck2020.be), and for the sumptuous accompanying publication that is the subject of this review.

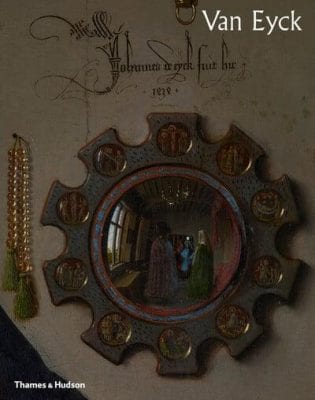

Originally released by Hannibal Publishing under the same title as the exhibition but simply called Van Eyck by its UK/US publisher, this weighty book is not a traditional exhibition catalogue; there are no individual entries for the exhibited artworks and no checklist is included. To judge from the virtual tour of the show, it appears that most of the exhibited works are illustrated but there is no way of telling which ones these are from the book alone. No doubt there were good reasons for forsaking the catalogue format, but the lack of individual entries is a pity. Both the Léal Souvenir and Baudouin de Lannoy portraits were specially cleaned for the show and so individual entries addressing their transformations would have been welcome. Lesser known works from Van Eyck’s orbit, like the Virgin of Engelendale, a rare Bruges sculpture of c. 1420 from the city’s Dominican convent (discussed briefly in Ingrid Geelen’s essay), are likewise crying out for entries. In contrast to the authoritative catalogue of the L’héritage de Rogier van der Weyden exhibition in Brussels (2013), which also closed early (albeit for different reasons), this book does not serve as a permanent record of the Ghent exhibition in quite the same way.

Van Eyck consists of nineteen essays written by 27 authors, organized into four sections: “Historical context,” “An optical revolution,” “Artistic context and iconography,” and “Dialogue.” According to its introduction, the volume “sums up the current state of scholarship of Jan van Eyck’s art” (19); Larry Silver’s brisk survey of Van Eyck research certainly does this, while the essay by Jacques Paviot that follows, “The Van Eyck family,” usefully updates his 1990 documentary biography of the painter while underlining the importance of diplomacy in his court career. A multi-authored contribution on Van Eyck’s home and neighborhood in Bruges expands our knowledge of his milieu (and includes the detail that the Sint-Gillis parish where he resided was a notorious red-light district in the fifteenth century). Jan Dumolyn and Frederik Buylaert’s lengthy essay on “Van Eyck’s world” offers a rich bird’s-eye view of the socio-economic context in which the artist operated and situates him within the various urban networks that overlapped in the Burgundian Netherlands. Several essays focus on tangible elements of Van Eyck’s world that found their way into his pictures, ranging from glass and metalwork (by Heike Zech) and sculpture (by Ingrid Geelen) to tiles and carpets (by Wim De Clercq, Maxime Poulain, Jaume Coll Conesa, and Jan Dumolyn). Van Eyck’s representations of the natural world are well served by Matthias Depoorter’s essay. The author’s ornithological expertise illuminates Eyckian motifs such as the migrating birds flying in a V-formation which were sometimes misunderstood by his imitators, like the Master of Jean Chevrot, whose St George miniature in the Morgan Library’s book of hours features a formation of flying birds in which the V is unnaturally (and illogically) inverted.

Only a handful of essays focus on specific works of art. Guido Cornini offers a rather Italo-centric account of Van Eyck’s treatment of the Vera Icon, while The Virgin in the Church is the subject of Stephan Kemperdick’s contribution. He provides a thorough study of the Berlin painting and its various copies and derivations, and makes a plausible case that its lost facing panel included an exterior view of the church and might have featured Christ on the cross or the Man of Sorrows. Dominique Vanwijnsberghe’s essay includes an admirably succinct account of the historiography of the Eyckian miniatures from the Turin-Milan Hours together with his own tentative proposal regarding their creation. Noting hitherto overlooked connections with illuminations emanating from the county of Hainaut, he suggests that the Eyckian miniatures might have been commissioned by Margaret of Burgundy, Countess of Hainaut and widow of William of Bavaria, and were perhaps even conceived as a memorial to the late count.

Some well-studied aspects of Van Eyck’s work garner relatively little attention among these essays. Technical studies are largely absent (although Hélène Dubois surveys the conservation history of the Ghent Altarpiece), and topics such as Van Eyck’s drawings, his work as a portraitist, and his relationship with his Netherlandish contemporaries receive only passing mention. The perennial question of the origins of Van Eyck’s art is mostly bypassed too, having been examined in Rotterdam’s 2012 The Road to Van Eyck show. By contrast, substantial attention is given to his legacy, in contributions addressing the Ghent Altarpiece’s sixteenth-century reception (by Astrid Harth and Frederica Van Dam, as well as by Dubois), and his effect on manuscript illumination (by Lieve De Kesel) and on nineteenth-century painting (by Johan De Smet). Till-Holger Borchert’s essay, “Reflecting Van Eyck,” surveys the pan-European impact of Van Eyck’s art, ranging from the Polling Master in Upper Bavaria and Konrad Witz in Basel to Lluís Dalmau in Barcelona and Niccolò Colantonio in Naples. By contrast, Paula Nuttall’s contribution, “The other ‘optical revolution’,” focuses only on Italy and sets aside questions of influence to consider instead Van Eyck’s common artistic ground with his Italian contemporaries. It is all too apparent that their work often falls short of Van Eyck’s achievements, despite their shared representational goals. Fra Angelico’s Vatican St. Francis, for instance, looks almost crude compared to its Eyckian counterpart, although Nuttall persuasively argues that the friar’s picture is its own “small milestone” (407) in its innovative depiction of divine light.

As the exhibition’s title suggests, optics and optical theory feature recurrently in several essays contained in this volume. Bartolomeo Fazio’s comments that Van Eyck was “not unlettered, particularly in geometry,” and that he learned about “the properties of colors” from reading ancient writers like the elder Pliny act as a springboard for a number of contributions, most extensively in Maximiliaan Martens’s essay on Van Eyck’s “optical revolution.” Martens reexamines the case for Pliny’s influence on Van Eyck but also proposes that the artist was versed in geometry and optics through the work of the eleventh-century Arab mathematician, astronomer, and physicist known as Alhazen. While Fazio’s ekphrastic account suggests first-hand encounters with Van Eyck’s paintings, his biographical notes seem more grounded in Italian humanist criteria for assessing painting than in direct knowledge of the painter’s education and training. As forceful a case as Martens makes for Van Eyck’s familiarity with Pliny and the theories of Alhazen, actual proof remains elusive. Might the artist’s own formidable powers of observation and imagination, together with his technical virtuosity, alone account for his extraordinary paintings? Martens thinks not, but the extent to which Van Eyck’s art was beholden to the texts and treatises cited by some of the authors in this volume remains an open question.

Not only is the quality of the book’s illustrations superb, but the selection of juxtapositions made by its editors and designers is both thoughtful and stimulating. The introductory essay uses a sequence of ravishing details from the Washington Annunciation as a case study in close looking; the array of images of other works that follows is similarly rewarding. The reproductions of the black and white photographs of the leaves from the Turin portion of the Turin-Milan Hours, taken before it was destroyed by fire in 1904, are the best that I have seen. In some instances though, the images do not relate closely (or at all) to the text that they accompany, while in others – like De Kesel’s essay on Van Eyck’s influence on illuminators or Borchert’s essay on his European impact – the reader hungers for illustrations of the comparative artworks tantalizingly described in the text. In the grand scheme of things though, these are minor quibbles. This book is a major addition to the rapidly expanding shelf of recent literature on Van Eyck; its expert contributors should be congratulated.

Douglas Brine

Trinity University, San Antonio