When one looks deeply at a Vermeer, one often borrows – however contingently – a lover’s rapt gaze. As Edward Snow observed, the painter’s “most profoundly dialectical”[1] tendencies hold the viewer’s perceptive and analytical faculties in tension – between the sense of visual presence that contradicts physical absence, or the ephemeral impression of momentary action and its eternal pause in paint. That these tensions should remind us of the back-and-forth pull of infatuation is no accident: the familiar Dutch proverb, “liefde baart kunst” (love gives birth to art) was in Vermeer’s time well-known to, and oft repeated by, those who made, analyzed, or were simply held fast in the sensual sway of art. This meditative and beautifully-illustrated volume examines the truth behind the sentiment, offering up love – earthly, divine, and metaphysical – as a potent conceptual framework for unpacking Vermeer’s stylistic and iconographic preoccupations.

The book is divided into two halves, each organized into short sub-sections. The first, “The Varied Faces of Love in Dutch Genre Painting,” profiles the circulation of visual and literary motifs of romance, courtship, and family life that would have been familiar to Vermeer as well as his patrons and peers. Brief essays explore familiar topics such as amorous emblem books and the ubiquitous symbol of Cupid, the close ties between music and flirtation, masculinity and “hunting” for love, images of prostitution and procurement, moralizing images of chaotic and harmonious families, and so on. The complexity of these themes – and their often ambivalent or paradoxical presentations – demonstrates what Georgievska-Shine terms a “cultural fixation on hypocrisy” (48), spurred by the inherent contradictions between ideal and lived realities, as well as the restless uncertainties of early modern Dutch life. In particular, the work of the fijnschilders – a group with whom Vermeer was in constant dialogue – is offered as a resonant metaphor, as the meticulous delicacy of their brushwork was frequently turned to suggestive compositions. Romance and courtship were necessary, but always in question, fraught with social pitfalls; painters’ “gently ironic” (57) treatments modeled and reflected these tensions. Georgievska-Shine manages to cover an enormously broad body of imagery and iconography in light, succinct, and well-illustrated chapters that function as primers for the meatier second half, “Vermeer’s Difference.”

In chapters 8-14, Georgievska-Shine digs into comparisons between Vermeer and his contemporaries in their depictions of music-making, letter-writing, and mirror-gazing, positing that Vermeer’s works are “more conducive to wordless contemplation” (10) than similar compositions and themes presented by peers such as Pieter de Hooch, Gabriel Metsu, or Gerard Ter Borch. Her comparison of the solitary quietude of Vermeer’s Woman with a Pearl Necklace against Ter Borch’s more narrative – and more populated – Young Woman at Her Toilette, convincingly affirms the former’s “tendency to suppress the anecdotal” (139) and return stilled focus to the interior life of both subject and viewer. The painter’s habitual removal of significant iconographic elements – a man and dog from A Maid Asleep; a map and lute from Woman with a Pearl Necklace – suggests a desire to elide theatricality in favor of absorption. Throughout, Georgievska-Shine affirms the “slowed” nature of Vermeer’s works, their insistent and evocative sense of pause, as the source of their potent grasp on attention and affection: this slowing-down of vision and apprehension, she argues, produces in the beholder a “lover-like absorption with the process of representation” (11).

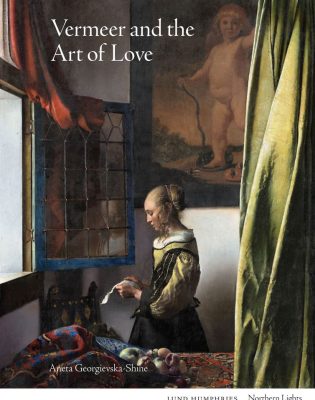

Romantic love and its captured likeness loom largest here. Vermeer’s own marriage to Catharina Bolnes is frequently mined: in a chapter titled “The Reappearing Cupid” Georgievska-Shine argues for the supposition that Catharina may have been a regular model and hints that the figure of Cupid now visible in Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window – obscured by later overpainting until 2021 – may render the picture a “personal homage” that “affirms… love as the source of all art” (70). Petrarch and his devotion to muse Laura, as well as the works of humanist poet Pietro Bembo, undergird discussion of Woman in Blue Reading a Letter and A Lady Writing; like the poets, Georgievska-Shine argues, Vermeer is “composing a paean to his beloved” and “invoking a moment of perfect correspondence between himself and his lady” (108). As the identity of Vermeer’s models remains an open question, more compelling are her examinations of the infatuated effect that images reproduce in the viewer. In “Returning the Lover’s Gaze,” Georgievska-Shine examines tronie heads and the power of painted glances to summon response – and compel love. Drawing on period sources from Franciscus Junius’ “unspeakable admiration” to Samuel van Hoogstraten’s “saturated” sense of astonishment at a portrait’s beauty (115), she affirms that the desire evoked by paintings (particularly paintings of beautiful women) was understood to be as real as the desire brought forth in the presence of one’s beloved.

Chapter 13, “Metaphysical Love,” relocates love from its earthly context to a heavenly one, in an appraisal of Woman Holding a Balance. Is this figure a spotless Virgin or a pregnant wife, or both simultaneously? Georgievska-Shine explores the dichotomies of purity and impurity, corporeality and spirituality, with the mysteriously empty balance at center, passing in turn through Jesuit theology, Stoicism, and Erasmian humanism enroute to Vermeer’s Allegory of the Catholic Faith. As she notes, the first known description of the latter, penned in 1699, reads “a sitting woman with more than one meaning, depicting the New Testament” (127), confirming that its evocative ambiguity was recognized even shortly following the artist’s passing. She presents Vermeer’s composition as a “Pauline mirror” of a visible world acting in service of the invisible and inexplicable which lies beyond it – a process of revelation that Georgievska-Shine ultimately terms “the metaphysics of love” (131).

The book’s insistence on absorbed devotion as a mode of viewing is replicated in Georgievska-Shine’s close attention to detail, her explorations of Vermeer’s unusual and abstracting techniques, and her lingeringly poetic descriptions of romantic “first glances” imagined between painting and observer. While there may be few major surprises here for readers already familiar with the significant body of scholarship exploring Vermeer through the concepts of love, courtship, and correspondence, this book still delights, and will provide an especially fresh and useful approach to Vermeer’s oeuvre for students and interested non-specialists.

A final note on mechanics: perhaps to appeal to non-specialists, the author eschewed the convention of naming paraphrased sources within the body of her text (except for period sources, which are directly named). This decision forces readers wishing to follow her arguments to pause and track down essential information in the endnotes, a time-consuming and potentially frustrating process. That Vermeer’s oeuvre is such well-trodden ground compounds the issue. Vermeer and the Art of Love engages in productive dialogue with works on Vermeer and love penned by Eric Jan Sluijter, H. Rodney Nevitt Jr., and Michael Zell, among others. Yet, as continual endnote-hunting is necessary to follow these conversational threads, many finer points of this interchange will prove challenging for readers to parse. Regardless, Georgievska-Shine’s book remains a highly cogent, pleasurable look at Vermeer through loving eyes.

Elisabeth Berry Drago

Science History Institute

[1] Edward Snow, “Head of a Young Girl.” Salmagundi (Spring/Summer 1979, 44/45): 130.