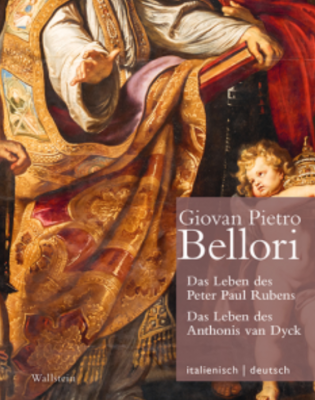

Fiona Healy’s commented edition of Giovan Pietro Bellori’s biographies of Peter Paul Rubens and Anthony van Dyck is the sixth volume of the bilingual Italian-German edition of Le Vite de’ pittori, scultori et architetti moderni (The Lives of the Modern Painters, Sculptors, and Architects) of 1672, prepared under the responsibility of Elisabeth Oy-Marra, Tristan Weddigen, and Anja Brug. The book bridges a gap in the otherwise rich scholarly literature on the early biographical contextualization of the two Flemish artists. It was a wise decision to treat the lives of the two artists, connected through a teacher-pupil relationship, in one volume rather than in isolation from each other. Scholars have occasionally puzzled about the fact that Bellori included Rubens and Van Dyck among the twelve exemplary “modern” artists in the first part of what was originally planned as a two-part book, but whose second part never materialized. However, Bellori began to assemble material on Van Dyck – and most probably also Rubens – already in the mid 1640s, after the two artists had died within a year of each other in 1641 and 1640, respectively, and the fame of Rubens had reached its zenith. At the beginning of his–, Bellori speaks of a shining light that appeared in Antwerp (which he erroneously believes to be the painter’s birthplace) at the hour of Rubens’s birth, thus emphasizing his decisive role in the renewal and ennoblement of the visual arts (pp. 12–13). In a similar way Karel van Mander, in the Schilder-Boeck of 1604, had already framed Jan van Eyck’s birth as a miracle manifested by a “brilliant and resplendent light” (“claer blinckende licht”).[1]

With the exception of a short trip south of Rome, Bellori never left his hometown during his lifetime and thus knew only a very few of these artists’ works from his own experience. This makes all the more interesting the question of which networks of collectors and connoisseurs Bellori used to assemble all the information, which he then weaved into a convincing account of the roles of the two Flemish painters in the advancement of the arts. In his life of Van Dyck, Bellori mentions that he had received valuable material on Van Dyck from Sir Kenelm Digby (1603–1665), one of the artist’s most important patrons when he was staying in Rome in 1645 and 1646, negotiating with Pope Innocent X for support for the Royalist cause in England (pp. 166–67). According to Healy, Digby – who served as chancellor to Queen Henrietta Maria after she had fled to Paris – might have acted as a middleman in providing Bellori with information or even a (no longer extant) set of oil sketches by or after Rubens for the cycle on the life of Maria de’ Medici (Henrietta Maria’s mother) in the gallery of the Palais du Luxembourg. Bellori’s rather precise description of the colors, which exactly matches the actual paintings, would speak for that assumption. The central role the cycle plays in Bellori’s fashioning of Rubens makes it less likely that Rubens copied the passage from another written source, as has been previously suggested (pp. 224–270).[2] In Bellori’s view, “in these compositions Rubens displayed his great swiftness of hand and the fire of his spirit, having worked with marvelous assurance and freedom of his brush. […] This gallery surpasses every other work of his, and in it, all the best strokes of his brush shine forth” (pp. 56–57).[3] As already suggested by Arnout Balis, Digby might also have told Bellori about Rubens’s so-called Theoretical Notebook, which the Italian describes as containing “observations about optics, symmetry, proportion, anatomy, and architecture, and a study of the principal affetti and actions drawn from descriptions by poets, with demonstrations of these by painters” (“un libro di sua mano, in cui si contengono osservazioni di ottica, simmetria, proporzioni, anatomia, architettura, ed una ricerca de’ principali affetti ed azzioni cavati da descrizzioni di poeti, con le dimostrazioni de pittori,” pp. 112–113).[4] As for Van Dyck’s Genoese portraits, Healy convincingly suggests that the Antwerp art agent Cornelis de Wael (1592–1667) who hosted Van Dyck during his stay in Genoa and later moved to Rome could have acted as Bellori’s informant (p. 222).

In current scholarship, Bellori’s life of Rubens has long been eclipsed by Roger de Piles’s (1635–1709) more detailed Abrégé de la vie de Rubens of 1677, based on information the French critic received from a broader variety of sources including Rubens’s nephew Philip and also Bellori himself whom he met in Rome between 1673 and 1674. While aware of the shortcomings of Bellori’s biography vis-à-vis that of De Piles, Healy explores the two lives from a new perspective by focusing on the ways in which Bellori framed the two Flemish painters, who had both spent formative years in Italy, as distinct, but complementary artistic personae, each with his unique painting style, preference for subjects and genres, and each of course also with his own individual imperfections. At the core of Bellori’s Rubens biography are the large commissions for the decoration of the gallery of Maria de’ Medici (pp. 34–59), the cartoons for the Triumph of the Eucharist tapestries, given by the Infanta Isabella Clara Eugenia to the church of the Descalzas Reales in Madrid (pp. 60–69), and the sketches and paintings for the triumphal entry of Cardinal Infante Ferdinand into Antwerp (pp. 70–97). Bellori also discusses Rubens’s altarpieces for the churches in Rome, Antwerp, Brussels, Ghent, and Lille, but not his mythological works apart from briefly mentioning his copies after Titian’s poesie (pp. 58–59) and the canvases with the stories from Ovid’s Metamorphoses made for the Torre de la Parada, the hunting lodge of Philip IV. Both Rubens and Van Dyck are introduced as great colorists for whom the experience of Venetian painting had been formative for their approach to color. But whereas Rubens’s coloring is described as a “force” (“forza”), infusing his painted historical narratives with life, Van Dyck’s refined use of color is praised for its pleasing and graceful effects (“grazia”), as especially visible in his portraits. Healy convincingly shows that for Bellori Rubens and Van Dyck represented two different approaches to and uses of (Venetian) painting, either in the service of history painting, ranking at the top of the hierarchy of genres, or for portraiture, the slightly lesser genre, but which allowed for the animated display of life-likeness, and, above all, also ensured a steady flow of income. Born in the imperfect art world of Flanders, their works were also characterized by flaws. Rubens’s singular creative freedom by which he achieved the most stupendous effects of color and movement “in one dash of the brush” also made him, in the eyes of Bellori, distort the great models of antiquity by transforming them into his own style (pp. 116–19).

For art historians interested in the early history of the critical reception of Rubens and Van Dyck, Healy’s edition of Bellori’s biographies of the two artists is a highly recommended reading. Her extensive annotations provide the most up-to-date bibliographical information of these two artists’ works. Her lucid essay not only lays the foundation for a critical comparative analysis of Rubens’s and Van Dyck’s different painterly languages, but also opens up a window into the valorization of Flemish painting in seventeenth-century Europe and the way it shaped the perception of the two artists up to the present time.

Christine Göttler

University of Bern

[1] Karel van Mander, Het Schilder-Boeck, Haarlem 1604, fol. 199r.

[2] Donatella Sparti, “Bellori’s Biography of Rubens: An Assessment of its Reliability and Sources,” Simiolus: Netherlands Quarterly for the History of Art 36, no. 1/2 (2012: 85–102, at 94–96.

[3] Here cited from Giovan Pietro Bellori, The Lives of the Modern Painters, Sculptors and Architects: A New Translation and Critical Edition, ed. Hellmut Wohl, trans. Alice Sedgwick Wohl, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005, p. 198.

[4] Cited from Bellori, The Lives of the Modern Painters, 205. See Arnout Balis, “Rubens und Inventio: Der Beitrag seines theoretischen Skizzenbuches,” in Rubens Passioni: Kultur der Leidenschaften im Barock, ed. Ulrich Heinen and Andreas Thielemann (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2011), pp. 11–40.