The early modern Netherlands were, statistically speaking, a land of women: estimates suggest that during the seventeenth century women outnumbered men four to three. These women were not only subjects of art, but makers and consumers. And yet it is still possible to open a twenty-first century survey of Dutch or Flemish art and encounter no images made by women, or few references to their role in shaping artistic cultures. Women Artists and Patrons in the Netherlands, 1500–1700, edited by Elizabeth Sutton, is therefore a timely intervention for the field of Netherlandish art at large. Not only does it offer a useful selection of case studies, the book issues a provocative call for greater scholarly self-reflection on the systems that continue to erase, downplay, or omit women’s names, tastes, artistry, and labor. As this collection convincingly demonstrates, the continued relative obscurity of Netherlandish women artists today is not merely a consequence of historical circumstances but also formed by choices that reflect contemporary priorities.

Originating from a panel titled “Women Artists and Feminist Historiography in and of the Netherlands,” an Historians of Netherlandish Art affiliated session at the 2017 Southeast College Arts Conference, the volume takes inspiration from Linda Nochlin’s seminal 1971 essay, “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” (Nochlin is mentioned in multiple chapters as well as the introduction, which is understandable if slightly repetitive). Sutton’s introduction is joined by six essays, each focused fairly tightly on a particular woman (or two): three painters, one patron, and two printmakers or print publishers. While some names may be familiar (Judith Leyster, Amalia van Solms) each of the essays highlights a lesser-known aspect of their creative identities, in order to make a greater point about the way these women have been misrepresented or neglected.

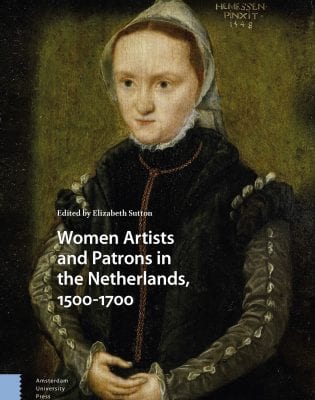

Part of the work that Sutton describes in the introduction, the attempt to render visible “how open the pathways are to do art history differently,” (23) involves re-evaluating hierarchies around labor, media, and topics as fraught as “originality.” As Sutton and others point out, women artists often operated by necessity in fluid spaces between the amateur and the professional, between the trailblazing and the stylistically conservative, between capital-a Art and “craft.” This was the case for Catharina van Hemessen, whose self-portraiture is brought into fresh focus here by Céline Talon. Van Hemessen’s use of highly conventional imagery, specifically the iconography of Saint Luke painting the Virgin, to craft a subtly unconventional representation of a female painter at her easel speaks to women’s frequent need to tread lightly when breaking new ground. Likewise, in her compelling reappraisal of the career of Magdalena van de Passe, Amy Reed Frederick notes that in addition to virtuosic reproductive engraving, too often treated by scholars as imitative byproduct, Van de Passe was also granted a privilege in 1630 to produce printed caps and linens. At that time, she was the only person in the Dutch Republic to hold such a right. Reclaiming both reproductive printmaking and wearable art is therefore not only an overturning of stale hierarchies (copy versus original, hand versus mind) but a recognition of the chronic devaluation of fields inhabited by women.

Even those women whose names and careers have received sustained attention are often pigeonholed and offered up as solo female counterweights within projects primarily concerned with men. In her essay exploring the nocturnal scenes of Judith Leyster and Gesina ter Borch, Nicole Cook notes the longstanding resistance towards incorporating women in general studies of Dutch painting, and instead to “treat their art as exceptional.” (56) The fashion for nighttime or chiaroscuro scenes in Dutch art is well-documented, but as Cook rightly argues, the specific potential of night for women creatives – as a time of relative liberation from household responsibilities and external perceptions – lends a vital new dimension to pictured darkness beyond Caravaggist imitation or sensual invitation. It suggests that even the most familiar, oft-scrutinized genres may remain only half-glimpsed, when women’s perspectives are not considered.

Recentering women’s interpretations of, and experiences with, art and artistic cultures is at the center of Lindsay Ann Reid’s essay on the Ovidian works of the princess Louise Holladine. Reid argues convincingly that Hollandine’s paintings of mythological “seductions” (an obscuring euphemism) carry an ominous note, depicting male gods’ trickery and pursuit as a “recurrent victimization of women.” (137) Such subjects were ubiquitous in art during Hollandine’s lifetime; as Reid points out, many of her contemporaries, including the poet Richard Lovelace, who penned a poem describing her paintings, typically treated such scenes as “light comic romance.” (136) It is perhaps difficult to imagine attempting a completely new account of the artistic reception of the Metamorphoses focused on women artists’ perceptions of the subject matter, but Reid’s essay suggests it would be well worth the effort.

Women artists dominate the volume, but women buyers of art also appear. Saskia Beranek’s thoughtful essay analyzes Amalia van Solms’s architectural, decorative, and garden design programs at Huis ten Bosch following the death of her stadholder husband. Beranek concludes that the palace, far from a mere memorial, provided a means of maintaining Van Solms’s social and political influence through art and spatial stagings that re-centered attention from the departed spouse to the living widow, highlighting a narrative of her endurance rather than her loss. Of the eight women whose lives and works are explored in depth in the book, Van Solms is the only one discussed solely as a consumer, rather than as a maker, of art. A valuable contribution even in isolation, this essay might have found more fruitful cross-connections alongside others on patronage and self-fashioning.

The theme of methodological self-reflection also runs alongside the collection’s overtly feminist drive to name and reclaim. The last essay of the collection, Arthur DiFuria’s exploration of the lives and reputations of Mayken Verhulst and Volcxken Diericx, models one approach to the difficult work of scholarly self-reflection. DiFuria notes that scholarship – including his own – has often referred to Verhulst and Diericx solely as the wives or widows of their spouses, Pieter Coecke van Aelst and Hieronymous Cock respectively, and that this act of forgetting or de-naming has suggested their real historical obscurity. But as this chapter makes plain, both women were famed in the printing world – by their own names – in their own time, and well after their deaths. In other words, it was not their milieu that effaced their contributions and concealed their names, but our own. DiFuria critiques himself along with the others who have performed these omissions, in a passage that is transparent and affecting, when he notes that “[Diericx] has always been known” (161). It is our shared work, then, to make sure such names are not forgotten again.

The wide-ranging diversity of topics and themes at work here might, by some measures, be a weakness. But what this volume lacks in a singular coherence of approach, it gains in demonstrations of the many distinct paths available to researchers working to illuminate these lesser-trod corners. As Sutton notes in the introduction, feminist perspectives are neither monolithic nor fixed, and an inclusive feminist pedagogy will be that which challenges hegemony and invites community; the voices that are raised by this process may therefore not always speak in unison. Overall, this is a vital and highly recommended volume that hopefully heralds new directions to come.

Elisabeth Berry Drago

Science History Institute