Jeremy Dupertuis Bangs (1946-2023) is well known as an art historian and archivist of the land and inhabitants of Plymouth, Massachusetts. He is less familiar as an artist and novelist; his skills converge in De kunst van de scriptie (2023), in which a few thinly disguised Leiden personalities feature in his own drawings, and in which the conflicted interests of art history graduate students are brought to the fore. His most absorbing efforts for the last decades involved the establishment of the Leiden Pilgrim Museum, which opened in 1997. The previous year Jeremy had secured the location for the museum in the oldest known house in town, built around 1370, and proudly he showed it to me: a ground floor spread of two rooms, empty and dark, with a smaller lower space as a root cellar. I would revisit it in July of this year and find it thriving.

Born in Astoria, Oregon, Jeremy was raised in Chicago and Missouri; he attended the University of Chicago and the University of Leiden, where he earned his Ph D (1976). His dissertation on 16th century Dutch tapestries and church furnishings led to a position in the Leiden Municipal Archives, where he became the expert on the Pilgrim stay in Leiden. In 1986 he was Visiting Distinguished Professor of Art History at Arizona State University. From 1986 to1991 he was Chief Curator of the Plimoth Plantation Museum in Plymouth, Massachsetts (now Plimoth & Patuxet Museums), where he strengthened the permanent collection. From 1991 to 1996, he was Assistant Archivist of Scituate and Visiting Curator of Manuscripts at Pilgrim Hall Museum, Plymouth; he examined land transactions between early colonists and the Indigenous people. Returning to Leiden with his wife Tommie Flynn, he founded the Leiden Pilgrim Museum.

Jeremy wrote many articles and over twenty books. Within art history, these include Cornelis Engebrechtsz.’s Leiden: Studies in Cultural History (1979) and Church Art and Architecture in the Low Countries Before 1556 (1997). Turning his interest to the archival wealth of Massachusetts, he wrote indefatigably; among his books on the area around Plymouth are Pilgrim Edward Winslow: New England’s First International Diplomat (2004), Indian Deeds: Land Transactions in Plymouth Colony (1620-1691 (2002, 2008), Strangers and Pilgrims, Travellers and Sojourners (2009), Plymouth Colony’s Private Libraries (2018), New Light on the Old Colony: Plymouth, the Dutch Context of Toleration and Patterns of Pilgrim Commemoration (2020), and Josias Wompatuck and the Titicut Reserve of the Mattakeeset-Massachusetts Tribe (2020).

His awards include the Pilgrim Academic Research Award (2017), Knight of the Order of Oranje-Nassau (2018), and an honorary wampum necklace from the Cothutikut Mattakeeset Massachusetts tribe (2019).

Jeremy was very well aware that he was pursuing less well trodden paths. He and Tommie, an artist, lived in one of the older, narrower and steeper houses in central Leiden, eclectically furnished and brimming with books and art. His notes to the recipients of his offprints acknowledged the obscurity of his subjects, but that did not make the topics less interesting. Among these topics was an examination of the mercantile activities of Daniel van der Meulen, who also happened to have owned the only known Venetian courtesan painting in the Dutch Republic before 1600. With his father, Carl O. Bangs, Jeremy co-authored an article on Socinians and Remonstrants in Leiden around 1600, some of whom were university students from Poland (1985-1986). In his survey of representations of the Pilgrims, largely of the 19th century, he brought in comparisons to Rembrandt. His wry sense of humor was his alone. And his command of archival Dutch was superb.

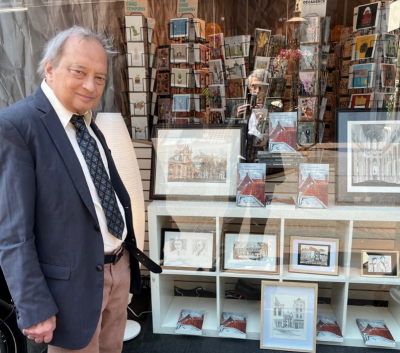

I was privileged to visit the Pilgrim Museum in the summer 2023 with Jeremy and Tommie. The museum was at capacity with visitors. The two rooms were filled with artifacts and furniture of the time of the Pilgrims or earlier. Displayed was a plethora of relevant objects, ranging from books, lace, tools, pots and stoneware to a child’s high chair, beads, buckles and church sculpture. Among the rarest items was a painted linen banner, probably from Haarlem, which depicts the instruments of the passion. Jeremy gleefully recounted his adventures in gathering these assorted treasures, a few on the street as throwaways, many gifts, and many more select acquisitions from private owners.

Jeremy’s dedication to the Pilgrim Museum made it a great success, and it will continue to flourish under the capable direction of Sarah Moine, Jeremy’s assistant of many years. He will be missed, as a scholarly pioneer, a skillful raconteur, and a friend.

Amy Golahny

Richmond Professor of Art History Emerita

Boston College Part-time Faculty