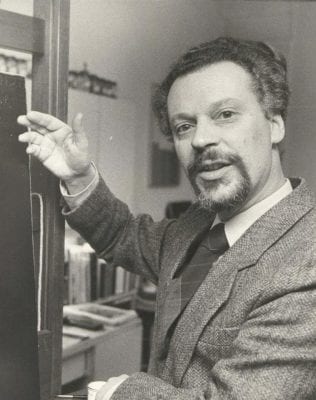

Identifying long-lost Old Master German drawings was something at which Tilman Falk excelled. He had a gift and an eye for drawings. Call it the work of a dogged scholar or able detective, Falk’s sleuthing was a persistent motivator and source of joy for him. It seemed that each time I saw him on my nearly-annual research trips to Germany, he either had identified a new drawing or shared with me a conundrum about a drawing newly come across in a private collection somewhere. My memories of these encounters surely are already accruing the distorted glosses of an encomium, but they are sentiments I suspect are shared by others like myself who held this art historian in high esteem, professionally and personally. Tilman Falk passed away this summer in July 2020.

Herr Doktor Falk was born in 1935 in what was then Breslau, Germany (now Wroclaw, Poland). He studied in Tübingen and Berlin, and began a long career working as a curator in some of the finest collections in western Europe, first at the Cologne Wallraff-Richartz-Museum and on to Otto Schäfer’s Grafiksammlung in Schweinfurt. For nearly eleven years he oversaw the Basel Kupferstichkabinett, with key exhibitions and publications on German Old Masters, including Lucas Cranach. Gemälde, Zeichnungen, Druckgraphik: Ausstellung im Kunstmuseum Basel (1974) with Dieter Koepplin, and Katalog der Zeichnungen des 15. und 16. Jahrhunderts im Kupferstichkabinett Basel (1979) with Christian Müller. For eight years he served as Director of the Augsburger Kunstsammlungen, a city where people still remember his multi-media exhibition on the Rococo artist Matthäus Gunther (1705–1788) from 1988. Capping his glorious career as head of the Staatliche Graphische Sammlung in Munich, Falk there produced other memorable exhibitions, such as on Martin Schongauer, on the artist’s 500-year death anniversary (Martin Schongauer, das Kupferstichwerk: Ausstellung zum 500. Todesjahr, 1991), and catalogued the collection’s fifteenth-century German drawings (with publication in 1994). I digress from chronology to save for last Falk’s area of expertise that is closest to my heart, on the Augsburg artist Hans Burgkmair (1473–1531). Falk’s Hans Burgkmair. Studien zu Leben und Werk des Augsburger Malers (1968) was the subject of his dissertation but a subject to which he continued to return with systematic attention and passion throughout his life, collaborating on an exhibition and extensive catalog of the artist’s graphic oeuvre in 1973, and passing away before completing what no doubt would have been the final word on Burgkmair’s drawings.

As a once-junior scholar writing a dissertation myself on Burgkmair fifteen years ago, I shall value the numerous conversations we had about our shared interests, his patience with my questions, his generosity in sharing newly attributed red chalk drawings with me, his utter decency in treating me with civility and kindness, despite my best efforts to catch up with his decades’-long experience with the material. For all of his international renown as a Burgkmair expert, Tilman (for here I turn to first-name basis) was above all welcoming to me, never patronizing or dismissive; he was confident in certain strongheld opinions and ideas about Burgkmair, but remained open-minded to most others, even from junior scholars like myself.

It seems fitting here to invoke one of Burgkmair’s best-known images: the Sterbebild woodcut for Conrad Celtis from 1507–08. In this printed epitaph the scholar-poet Celtis appears as if on a simulated stone memorial. He is draped with laurels, eyes downturned and hands clasped over volumes representing his publications. Among the Latin inscriptions on the epitaph are the words: LONGVM VIVVS IN EVVM COLOQVITVR DOCTIS PER SVA SCRIPTA VIRIS. Indeed, Tilman will continue to speak to us through his writings. His exhibitions and publications will live after him, especially his still-valuable research on Burgkmair. But we shall miss the man and mentor.

Ashley D. West

Temple University