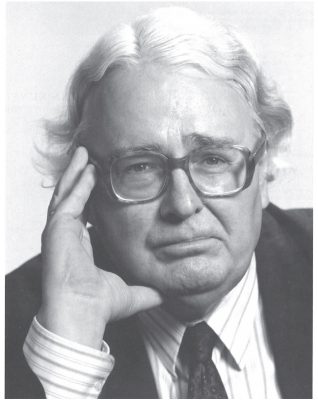

Obituary: Justus Müller Hofstede (1929-2015)

Justus Müller Hofstede, Professor emeritus at the University of Bonn, died on April 27, 2015, in his hometown. His death not only ended a long and full life but with it Netherlandish art history has lost one of its most distinguished personalities who has moulded art historical research – specifically on Peter Paul Rubens – since the 1960s. Beyond that, Müller Hofstede changed the landscape of German higher education when he founded the still only chair dedicated to Netherlandish art history at the Kunsthistorisches Institut of the University of Bonn, accompanying generations of students on their way.

Born on May 9, 1929, in Berlin, Müller Hofstede’s way to art history seems to have been preordained: his father Cornelius Müller Hofstede was director of the museums in Braunschweig and Breslau (now Wroclaw in Poland), later also of the Gemäldegalerie, Berlin, and on the paternal side he was related to Cornelis Hofstede de Groot. Yet he initially studied theology in Berlin only to switch to art history in Heidelberg in 1949, eventually moving to Freiburg where his teacher was Kurt Bauch who became a model for him. He received his Ph.D. in 1959 with a dissertation on Otto van Veen. This was followed by a three-year postdoc at the Zentralinstitut für Kunstgeschichte in Munich. During a research stipend from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft from 1962 to 1967, Müller Hofstede traveled extensively to Italy, The Netherlands, Belgium, France, Spain, England and even St. Petersburg (then Leningrad) and Moscow, to work in libraries and archives but also to study works in the original. Many of his friendships and colleagual relationships formed during these years resulted in close and long-lasting scholarly exchange. In December 1967 Müller Hofstede received his habilitation at the Rheinische Friedrich Wilhelms Universität in Bonn, advancing to Academic Council and Professor of Art History in 1970. He remained in Bonn until his retirement in 1994, even declining a call to Berlin in 1982. This loyalty and attachment were not limited to Müller Hofstede’s scholarly world but extended to his personal life – to people who were close to him but also to his values and commitments, many of which derived from his studies and research. It is not incidental that his occupation with Peter Paul Rubens became the central theme of his life.

This becomes especially apparent in the 1992 article about Rubens’s self-portraits in which he deals with the intellectual world of this extraordinary artistic personality, revealing the multi-layered levels of meaning of these self-representations. As always, he saw the great Flemish painter within the context of a self-image shaped by Justus Lipsius and the neo-stoic intellectual world. The ideal of constantia – an inner steadfastness combined with vigor even in times of adversity – , virtus, and the calling to an active vita civilis were principles which Müller Hofstede recognized as formative for Rubens but which were equally relevant to his own life. Thus he applied himself with great commitment to things for which he felt responsible. Since 1972 he worked on various university committees, was, among others, a member of the university senate and pro-rector from 1988-1992. His special obligation as art historian was the duty to awaken consciousness for art in its significance for man and his world. Thus he was engaged in the conservation of monuments and the preservation of the historic cityscape of his hometown, Bonn, for which he received, besides other high honors, the Verdienstkreuz I. Klasse of the Verdienstorden (1st Class Cross of Merit of the Order of Merit) of the Federal Republic of Germany.

Müller Hofstede’s intensive occupation with “Rubens in Italien”, which resulted in the large 1977 exhibition in Cologne, reveals much of his interests, for he interpreted this period after Rubens’s apprenticeship and early years as free master in Antwerp as a turning away from his teacher Otto van Veen and his pictorial conception formed above all by literary and emblematic concerns towards a direct confrontation and dialogue with the work of art. This approach, that the aesthetic experience constitutes a component pictorially as well as in meaning informed the seminal article on Pieter Bruegel’s concept of landscape (1979). Justus Müller Hofstede demonstrated at hand of the drawings that with Bruegel the contemplation of nature becomes an aesthetic experience shaped by stoic philosophy of nature. In the debate starting in the late 1970s on the meaning of iconological research in Dutch painting he took a decisive stand in the volume edited jointly with H.W.J. Vekeman, Wort und Bild in der niederländischen Kunst und Literatur des 16. und 17. Jahrhunderts, published in 1984. For him emblem and the representation of reality do not constitute opposites but complementing and, in their function, ultimately self-ascertaining principles. The fruitfulness of such iconological interpretation is demonstrated by his contribution on the allegory of sight in the same volume.

Already in his earliest publications, starting in 1961, Müller Hofstede dealt with drawings and oil sketches. As embodiment of spontaneity and individuality, he viewed them as part of a creative process in which painters assured themselves of their idea and its form of expression which they then refined. The special interest in a theoretical as well as practical development explains his repeated occupation with the early work of an artist. This search for the perfect form, the assurance of one’s artistic goals at the beginning of a career, the striving for one’s place in the social fabric – all that corresponds in astonishing ways to his extraordinary interest in his students, many of whom he supported intensely and accompanied on their way. He was in the truest sense of the word a “Doktorvater.” Thus it comes as no surprise that many of his students remained closely connected to him beyond their university years.

Müller Hofstede’s manifold interests resulted in a broad thematic spectrum that included the early Italian Renaissance, Mannerism and even classical modern art, as reflected in the multitude of dissertation topics which he supervised. It stands to reason that many who experienced him as teacher found their way into museum work. Numerous excursions to museums at home and abroad taught us – and I count myself here as one of his students – to train the eye in front of the original and to understand that looking at a painting also is a sensual experience. One would encounter MüHo (as he was affectionally known) at symposia and lectures in the company of his students for whom the meeting with like-minded colleagues offered an early introduction into the scholarly world. He lived the ideal of a teacher whose expression he had found in Rubens’s friendship portraits in which the formative influence of Justus Lipsius is reflected.

Justus Müller Hofstede was a distinctive personality: impulsive, incisive, and, by all means, also dominant. This did not make the association with him easy for everyone. However, those who valued and liked him, have lost an extraordinarily stimulating, erudite, open-minded and genial human being. For many he was a true friend.

Mirjam Neumeister

Alte Pinakothek

(Translated by Kristin Belkin)